Last year Altmann, Pierrehumbert & Motter (henceforth, APM) released a great paper in PLoS One: Niche as a determinant of word fate in online groups. Having referenced the paper extensively in my non-bloggy academic world, I thought it was about time I mentioned it on a Replicated Typo. Below is the abstract:

Patterns of word use both reflect and influence a myriad of human activities and interactions. Like other entities that are reproduced and evolve, words rise or decline depending upon a complex interplay between their intrinsic properties and the environments in which they function. Using Internet discussion communities as model systems, we define the concept of a word niche as the relationship between the word and the characteristic features of the environments in which it is used. We develop a method to quantify two important aspects of the word niche: the range of individuals using the word and the range of topics it is used to discuss. Controlling for word frequency, we show that these aspects of the word niche are strong determinants of changes in word frequency. Previous studies have already indicated that word frequency itself is a correlate of word success at historical time scales. Our analysis of changes in word frequencies over time reveals that the relative sizes of word niches are far more important than word frequencies in the dynamics of the entire vocabulary at shorter time scales, as the language adapts to new concepts and social groupings. We also distinguish endogenous versus exogenous factors as additional contributors to the fates of words, and demonstrate the force of this distinction in the rise of novel words. Our results indicate that short-term nonstationarity in word statistics is strongly driven by individual proclivities, including inclinations to provide novel information and to project a distinctive social identity.

There are lots of nice aspects to this paper and the authors seem to strike the right balance when pushing their analogy between species’ niche and the word niche. For me, at least, it provides a good example of taking ideas and insights in one field and fruitfully transplanting them into another. So, as in ecological niches, where diversity and viability are central concepts, the relative extent of the word niche is strongly associated with the likelihood of a favourable or unfavourable fate. These general statistical trends can, however, be overcome by exogenous events: throughout evolution we’ve seen how historically contingent factors, such as asteroid impacts, can strongly influence future trajectories (also see Black Swan Events). So too is it true for words: inventions and wars, to take but two examples, ensure there is plenty of perturbations in the cultural system.

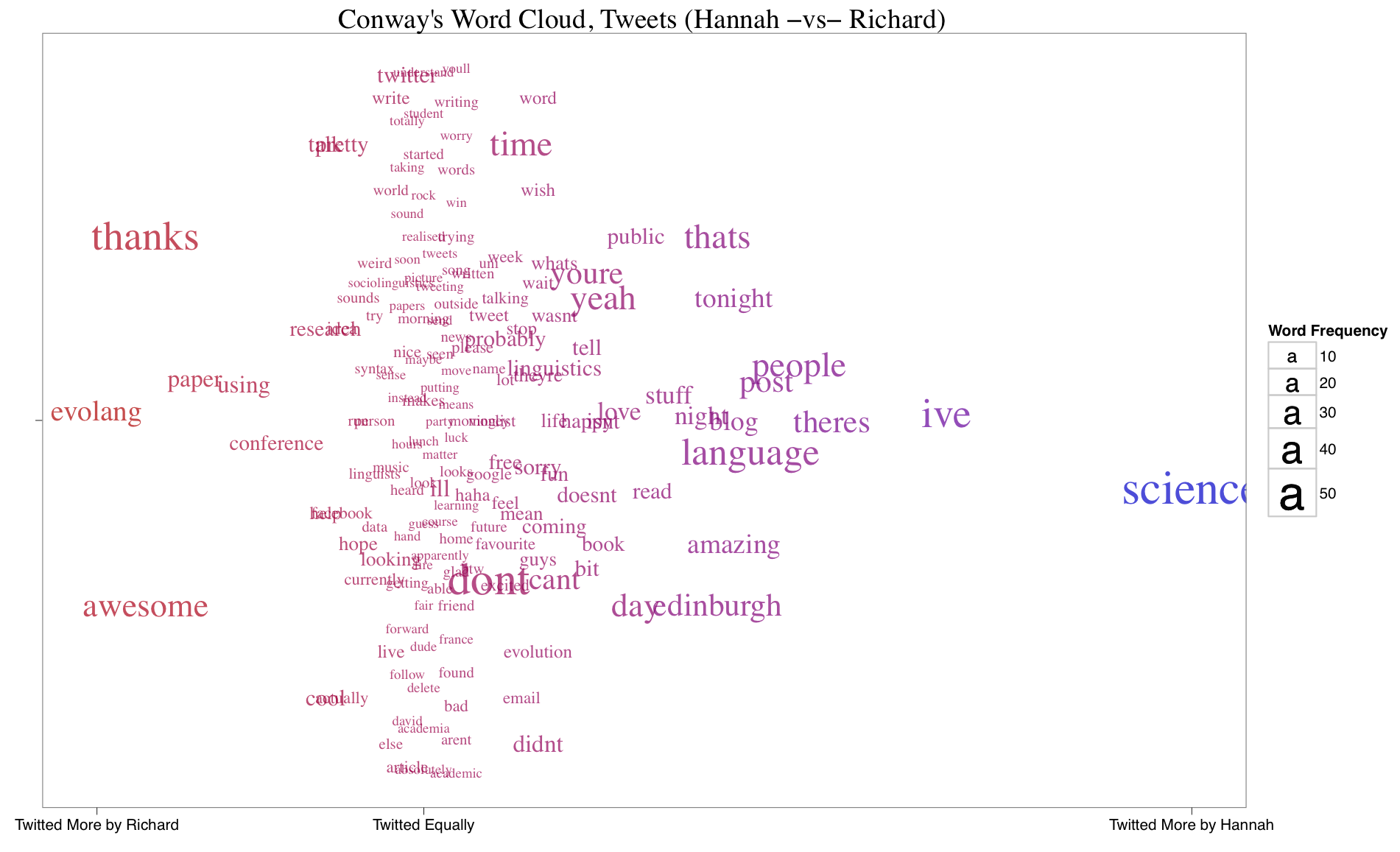

As for their dissemination across users: we’re essentially talking about a way of measuring the indexicality of words (to stick with sociolinguistic parlance): here, the use of words can become associated with certain individuals or types of people, and is also commonly referred to as lectal variation (Peirsman & Speelman, 2009). You can trivially show how words cluster according to individual proclivities by data mining Twitter. Taking two of our most popular tweeters, Richard and Hannah, I created a comparative word cloud based on their tweets (N.B. you should use the TwitteR package for R — it’s very easy to use and bloody brilliant):

As you can see, Richard seems to be going for the nice guy of Twitter of award, whereas Hannah is pretty much becoming synonymous with SCIENCE. The frequency count is obviously very context-specific (e.g. I did this a few months ago and, as you can see for Richard, evolang appears quite frequently) and it doesn’t really delineate between users and topics. Still, even if you don’t want to take my liberal use of Twitter API data too seriously, there is a point buried in amongst the triviality: clusters of words will emerge that are specific to indexicality and topicality of discourse. There is also a lot of overlap in the words they tweet at similar frequencies, which we would expect, given that they speak the same language and share a considerable overlap in vocabulary.

This leads to another possible way we could push APM’s analogy further and suggest that the dissemination profiles of words could reflect competition-colonisation trade-offs: in ecological niches, those species that are better competitors will become increasingly specialised, while species characterised by colonising tendencies are more likely to be generalists. You could hypothesise a similar scenario taking place in the lexicon: specialist words will cluster according to the users and topics, whereas generalists will not. What determines whether a word is a generalist or specialist is likely to be correlated both within (e.g. nouns denoting concrete, physical senses versus nouns that are considered maximally vague) and between (e.g. nouns versus prepositions) word classes.

We can provide a tentative demonstration of this based on data from APM’s paper: in a half-year window centred on 1998-01-01 in the comp.os.linux.misc group, the words thanks and redhat have almost identical frequencies, but contrast in their dissemination (thanks: number of words = 4,121, dissemination across users = 1.19; redhat: number of words = 4,146, dissemination across users = 0.75). Here, the expected value of dissemination across users is 1 based on the assumption of being randomly distributed, with over-disseminated being greater than 1 and clumped profiles being less than 1. We can consider thanks to show characteristics of generalists when compared to redhat (something that is very specialised to the context of the Linux group in which it appears).

APM also link word dynamics with a related concept in ecology, known as the exclusion principle (of the non-physics variety): here, species show a tendency to occupying distinct niches, thus protecting them from competition. Applied to words:

Because almost every word is learned with a distinctive meaning (or set of meanings), and replication has low error rates, it follows that most words do not have a direct competitor for exactly the same meaning and contexts of use. If an active competition between two forms develops historically, then both can survive if they develop distinctive roles within the space of the lexical, syntactic, and pragmatic components of the linguistic system.

Take the English future auxiliary gonna: this is a new competitor for the older future will, but they are both maintained in the population because gonna is preferentially used in some constructions (such as questions) and will is preferentially used in others (such as the main clauses of conditionals) (see Torres & Walker, 2010). It therefore makes sense that the long-term dynamics we see in language change stem (somewhat) from short-term dynamics of people interacting in ways that differentiate themselves and what they say (one last note: you should really check out Gareth Roberts’ paper on experimentally investigating the use of language to mark identity and how it ties in with language change and linguistic divergence).

Reference

Altmann EG, Pierrehumbert JB, & Motter AE (2011). Niche as a determinant of word fate in online groups. PloS one, 6 (5) PMID: 21589910

Brilliant stuff! Love it….

This is exactly right. I have talked about words in niches before to explain how the a word can coexist with earlier instances while it gradually gains a new meaning. The word hoped from social enviroment to social enviroment until its change in semantics allowed it to coexist by inhabiting a different semantic niche.