Update: I have carried out some more analyses that paint a different picture to the one presented below. Oops!

A recently accepted paper by Keith Chen has been getting a lot of press coverage. Chen has discovered a close link between the properties of the language people speak and their economic decisions. People who speak languages which mark the future tense differently to the present tense tend to make fewer provisions for the future. This includes economic decisions such as being less likely to save money, but also secondary indicators such as greater prevalence of smoking and obesity.

The hypothesis is that marking the future tense differently makes the future seem further away, and therefore you are less likely to plan for the future.

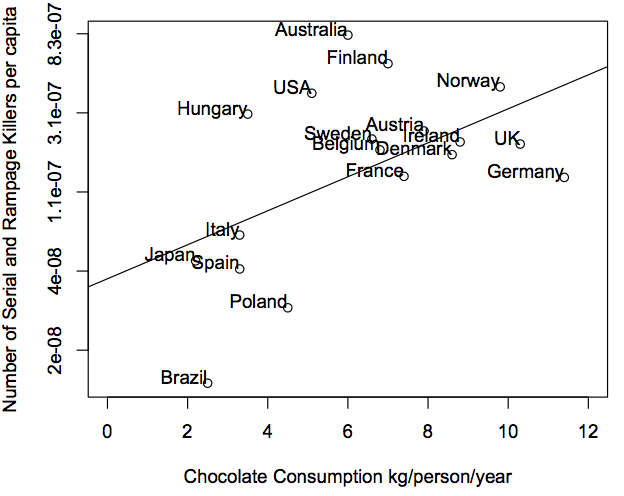

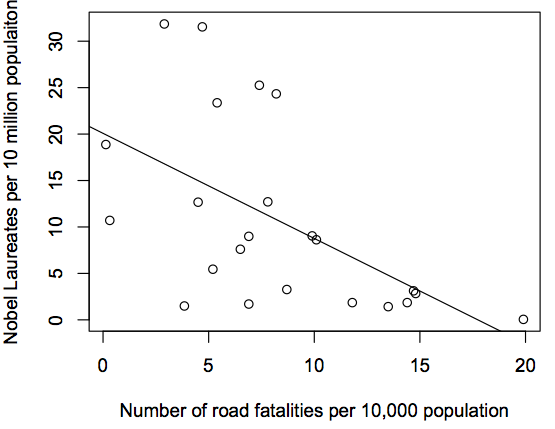

Chen has talked about this hypothesis at a TED conference and has been covered in the media, most recently in a BBC economics column (which, to be fair, was fairly critical). The hypothesis has been criticised by several linguists, notably on language log (and a great model post by Mark Liberman), where Chen gave a response. The data has been criticised (e.g. English is marked as ‘strong future tense marking’, but has a range of ways of using present tense for future time reference), as well as the thinking behind the hypothesis itself (e.g. why wouldn’t marking a difference in the language actually make the future MORE salient?). Some have also pointed out weaknesses in the statistical claim, for instance, Östen Dahl has pointed out that speaking a language with front rounded vowels is also a good predictor of economic decisions.

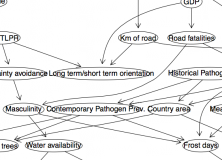

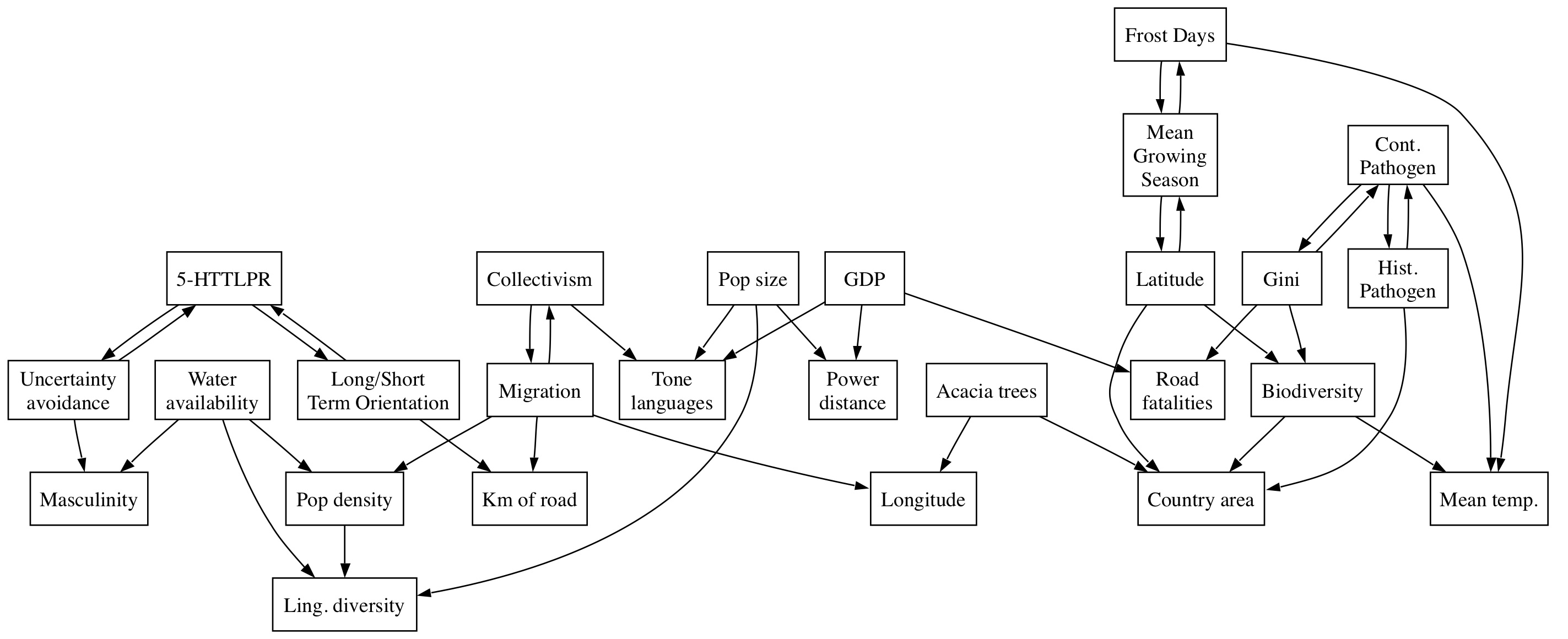

Here at Replicated Typo, we have discussed many cases of spurious correlations – statistical links between cultural traits that are unlikely to be causal. James Winters and I recently published a paper on the dangers of making claims based on large-scale, cross-cultural statistics. Basically, it’s very easy to find statistical links between any two variables because cultrual traits are inherited in bundles (they are not independent).

In this post, I address an issue that I haven’t seen systematically answered yet: Chen predicts that there is a correlation between future tense marking and economic decisions, and finds a strong link. However, he should also predict that future tense marking is a stronger predictor than other linguistic variables. In other words, can we find a different aspect of language that is even better at predicting economic behaviour? Here I test the link between the propensity to save money and many different linguistic factors.

Continue reading “Whorfian economics reconsidered: Why future tense?”