Yesterday I posted an analysis of some work by Prof. Keith Chen on the link between future tense marking and economic decisions. Prof. Chen made some suggestions about changes to the analysis, some of which I’ve carried out here. The new results below indicate that the link between future tense and the propensity to save is more robust than the previous post suggested, which is quite embarrassing, but I submit the findings here anyway.

One of Prof. Chen’s points was that I was using simple linear regression, while his analysis used conditional logit modelling. This is much more computationally intense, and it’s not feasible for me to run 145 logit models for the given size of dataset (R was telling me it needed 13GB of memory to run an analysis of one linguistic variable! Help, anyone?).

Another suggestion was to look at which linguistic variables explain the residual variation in a model with non-linguistic variables. That is, controlling for non-linguistic variables such as age, sex and number of children, how much extra variance does a particular linguistic variable account for?

I analysed this by comparing two models for each linguistic variable (using ANOVAS, although the results are equivalent with regressions). Each model had the propensity to save as the dependent variable and independent variables including age, sex, employment status, marriage status, level of education, religion, number of children and survey year. The second model also included the linguistic variable. I then compared the improvement in the model fit using the F-score of the difference in residuals. (There are some problems here, because different linguistic features will be represented in different sub-sets of the data, but we’ll ignore this for now.)

The results showed that there was only one other linguistic variable that improved the fit of the model more than future tense. That is, future tense was a better predictor than 99% of the linguistic variables. For comparison, Dediu & Ladd’s test of the link between linguistic tone and Microcephalin/ASPM found that the hypothesised link was stronger than 98.5% of many thousands of links between genetic and linguistic factors.

10 linguistic features had an F-score were within 1.96 standard deviations of the F-score for the future tense variable, suggesting that the future tense variable is a significantly better predictor than 93% of the linguistic variables. Here they are in order from most significant to least significant:

[1] Perfective/Imperfective Aspect

[2] FTR (the future tense variable used in Chen’s analysis)

[3] The Velar Nasal

[4] Consonant-Vowel Ratio

[5] Vowel Quality Inventories

[6] Plurality in Independent Personal Pronouns

[7] Consonant Inventories

[8] Inflectional Synthesis of the Verb

[9] Inclusive/Exclusive Distinction in Verbal Inflection

[10] Case Syncretism

[11] Periphrastic Causative Constructions

(descriptions of the variables can be found on the WALS website)

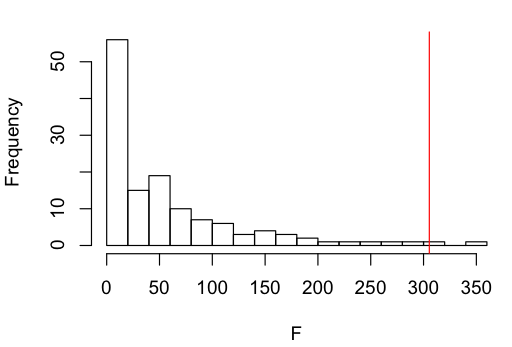

Here’s a histogram of the F-scores with the result for the future tense variable marked by a red line:

The future tense variable significantly improves the fit of the model over and above the model with the Perfective/Imperfective aspect (F = 19.04, p < 0.0001).

Discussion

That’s a very different picture from the one I suggested in yesterday’s post. While there are some other contenders, the future tense variable is arguably a valid predictor of propensity to save money in this analysis.

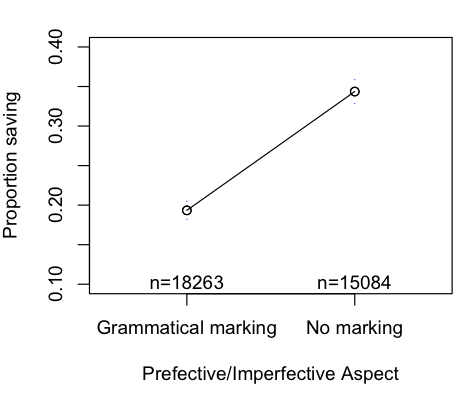

Furthermore, the one linguistic feature that’s better than future tense is the Perfective/Imperfective aspect (whether there’s a distinction in marking completed from ongoing events). Many languages have a link between tense and this kind of aspect. However, is there a link between this variable and economic decisions? Having a distinction between completed and ongoing events in the language is linked with saving less, so maybe it biases speakers with this system to feel that ongoing events are more difficult to complete, so why bother trying? Admittedly, I’m finding it a bit difficult to come up with a coherent story for this feature.

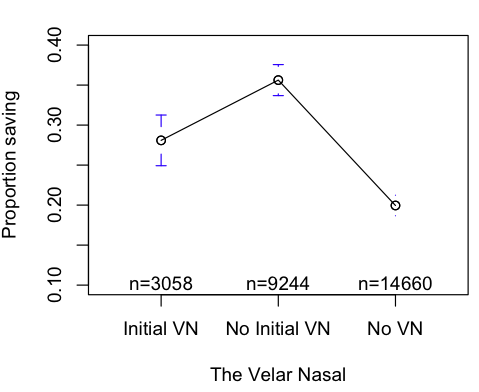

The Story may be even harder to imagine for velar nasals:

Causal Graphs

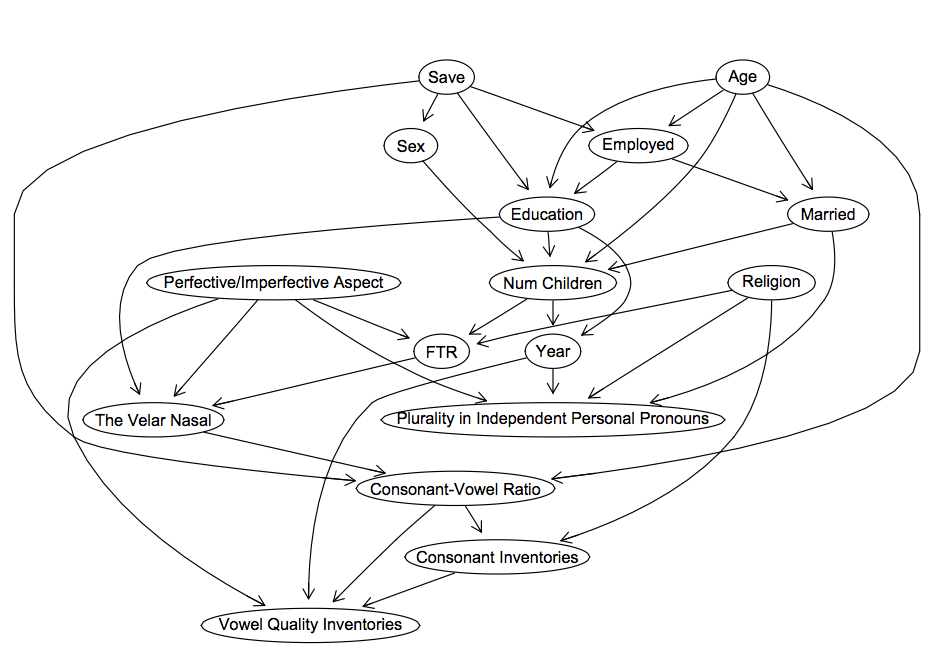

I tried creating some causal graphs of the network of relationships between the variables in the analysis. I used the PC algorithm supplied in R’s pcalg package (see more on this here). Here’s one of the results, using the top 7 linguistic factors (click to make big). (From my limited experience with this technique, the diagram is highly sensitive to the alpha parameter and the sub-set of data used. The presence of arrows is more robust than their direction, and links between some variables are more robust than others. As I mention here, there’s probably a way to bootstrap confidence intervals on the diagram links. I’m assuming Gaussian variables, because the discrete variable function for the PC algorithm in R isn’t working for some reason, and an alpha level of 1*10^-9, which is fairly conservative).

Several things about this graph make sense. For example, the number of children you have is linked with your sex, your level of education, your age and whether you are married. Age affects your employment status, your marriage status and your level of education. The consonant-vowel ratio is linked to whether there is a velar nasal, the size of the consonant inventory and the size of the vowel inventory.

With regards to Chen’s hypothesis, saving money (marked ‘Save’ above) is linked with employment, education, sex and (less accountably) consonant-vowel ratio (although this correlates with population size). There is a link between the propensity to save and the future tense variable, but only indirectly through other economic and social factors.

Removing the other linguistic variables, a similar picture emerges. There is a link between future tense and saving, but there are also complicated mediating links:

Conclusion

The evidence here supports a strong statistical link between future tense marking and the propensity to save money. This differs in degree from my previous analysis. It’s painful to go back on a claim made in such a public sphere as a blog, but it’s the scientific thing to do, so many thanks to Prof. Chen for suggesting this analysis. He has made other suggestions that would improve this analysis further, but I don’t have the time or computing power to carry them out.

However, there is still little evidence for a causal link between the two variables. The causal graphs above suggest that the link may be quite complicated. Furthermore, it still needs to be shown that the future tense variable really does reflect how people think about time.

There are two avenues that still remain largely unexplored for this hypothesis. First, lab experiments and models. Secondly, a phylogenetic approach (thanks to SK for pointing this out). I suggested one way to do it would be with partial mantel tests of data collapsed over languages and patristic distances based on the ethnologue. I’ve attempted this analysis, but run into problems. I’ll try again when I have more time.

It isn’t such a different picture. Chen’s proposal is still quite crazy.

Here is an earlier paper that Chan fails to cite whose results are in line with hers.

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1910011

” It’s painful to go back on a claim made in such a public sphere as a blog, but it’s the scientific thing to do, so many thanks to Prof. Chen for suggesting this analysis.”

Science at its best. Congratulations.

“the scientific thing to do.” A brave thing to do too! Well done, well done!

national savings rates change over decades. grammar over centuries.

Ha! Important update indeed. Are we to forget the future tense and to become rich?