![]() What makes humans unique? This never-ending debate has sparked a long list of proposals and counter-arguments and, to quote from a recent article on this topic,

What makes humans unique? This never-ending debate has sparked a long list of proposals and counter-arguments and, to quote from a recent article on this topic,

“a similar fate most likely awaits some of the claims presented here. However such demarcations simply have to be drawn once and again. They focus our attention, make us wonder, and direct and stimulate research, exactly because they provoke and challenge other researchers to take up the glove and prove us wrong.” (Høgh-Olesen 2010: 60)

In this post, I’ll focus on six candidates that might play a part in constituting what makes human cognition unique, though there are countless others (see, for example, here).

One of the key candidates for what makes human cognition unique is of course language and symbolic thought. We are “the articulate mammal” (Aitchison 1998) and an “animal symbolicum” (Cassirer 2006: 31). And if one defining feature truly fits our nature, it is that we are the “symbolic species” (Deacon 1998). But as evolutionary anthropologists Michael Tomasello and his colleagues argue,

“saying that only humans have language is like saying that only humans build skyscrapers, when the fact is that only humans (among primates) build freestanding shelters at all” (Tomasello et al. 2005: 690).

Language and Social Cognition

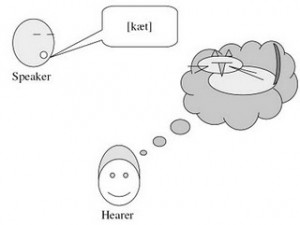

According to Tomasello and many other researchers, language and symbolic behaviour, although they certainly are crucial features of human cognition, are derived from human beings’ unique capacities in the social domain. As Willard van Orman Quine pointed out, language is essential a “social art” (Quine 1960: ix). Specifically, it builds on the foundations of infants’ capacities for joint attention, intention-reading, and cultural learning (Tomasello 2003: 58). Linguistic communication, on this view, is essentially a form of joint action rooted in common ground between speaker and hearer (Clark 1996: 3 & 12), in which they make “mutually manifest” relevant changes in their cognitive environment (Sperber & Wilson 1995). This is the precondition for the establishment and (co-)construction of symbolic spaces of meaning and shared perspectives (Graumann 2002, Verhagen 2007: 53f.). These abilities, then, had to evolve prior to language, however great language’s effect on cognition may be in general (Carruthers 2002), and if we look for the origins and defining features of human uniqueness we should probably look in the social domain first.

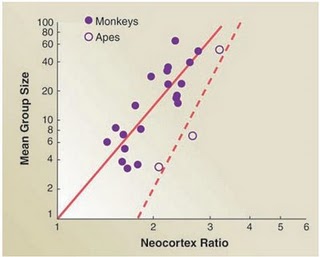

Corroborating evidence for this view comes from comparisons of brain size among primates. Firstly, there are significant positive correlations between group size and primate neocortex size (Dunbar & Shultz 2007). Secondly, there is also a positive correlation between technological innovation and tool use – which are both facilitated by social learning – on the one hand and brain size on the other (Reader and Laland 2002). Our brain, it seems, is essential a “social brain” that evolved to cope with the affordances of a primate social world that frequently got more complex (Dunbar & Shultz 2007, Lewin 2005: 220f.).

Thus, “although innovation, tool use, and technological invention may have played a crucial role in the evolution of ape and human brains, these skills were probably built upon mental computations that had their origins and foundations in social interactions” (Cheney & Seyfarth 2007: 283).

Language, Mental Representations, and Symbolic Thought

But this of course does not mean that we expect all other unique aspects of human cognition to be derivative of social cognition. The development of higher social cognition only presented the enabling context and cognitive starting point for other human mental capacities to evolve. To pick up the example again, language, for instance, does not only have an interactive function but also a symbolic one.

It creates ‘symbolic assemblies’ that function as form-meaning pairings (Evans & Green 2006: 6f.). But the ability to acquire arbitrary symbolic units itself does not appear to be uniquely human, as it has been demonstrated in great apes, parrots, dolphins and dogs (see Tomasello 2008: 254ff.). But there are two essential differences between the symbolic abilities of humans and other animals: Firstly, even with lexigram- or sign language-trained apes there appears to be nothing that even comes close to the production and joint engagement skills possessed by human children (production) or even pre-verbal infants (joint engagement) (Tomasello 2008: 109ff.).

Secondly, human symbols and concepts function as ‘decoupled representations’ which are not directly bound to a reaction pattern as in most other animal species, including symbol-trained animals, and enable significant “response breadth” and planning (Sterelny 2003: 29f.). In addition, symbolic thought and linguistic usage does not only rely on the comprehension and production of arbitrary signs, but essentially depends on our capacity for abstract, relational, analogical, higher–order, hierarchical and role–governed compositional thought. (Deacon 1998, Jackendoff 2007, Penn et al. 2008).

We now have two tentative candidates for what makes us special:

(1) The capacity to develop a shared point of view or “we-perspective” (Tuomela 2007: 46f.) and jointly engage in and attend to shared goals, plans and intentions in a cooperative collaborative activity within a joint attentional frame and a shared frame of reference (Tomasello et al. 2005).

(2) A conceptual system that is able to reinterpret and re-describe sensory as well as cognitive data and store them in an abstract, decoupled format that can be used for symbolic, relational and analogical reasoning (Penn et al. 2008).

We can now imagine a step in evolution where these two capacities were further integrated, yielding the analogical realization that others are “like me.” This then enables us to

(3) actively attribute mental states to others in the same sense as one experiences mental events and states oneself, that is to, have a “theory of mind” (Premack & Woodruff 1978).

Further, an integration of these capacities, and continuing collaborations and mutual engagements in social and other activities, would lead to the emergence of

(4) shared, intersubjectively overlapping frames of references or coordinate systems into which abstract and non-abstract conceptual representations could be integrated and imported in a systematic fashion, and within which shared percepts and concepts could be blended, unified, and related to each other in a role-governed fashion. (Bühler 1934,Fauconnier & Turner 2002).

In short, the first species in the hominin line who developed this capacity would not only have shared a perceptual world with his or her conspecifics, but they would inhabit a shared mental world. In this collective “we-perspective” and shared frame of reference mediated by joint engagement, they would then be able to create a shared “symbolic niche” in which meaningful cultural practices and shared symbolic constructs, such as institutions, could be co-created and which would ‘come alive’ and have actual real-world significance (Harder fc, Tuomela 2007).

By jointly attending to and attaching meaning to cultural artefacts and practices homo gave them intersubjective value and reality and created ‘institutional realities’ (Searle 1995, Moll & Tomasello 2007). Examples for this are all the things that only exist by virtue of everybody agreeing that something material (a brute fact, like a red light, or a piece of paper) stands for something else (a social, or instituational fact, like a traffic sign, or money.) It is probable that from the dawn of human culture cognition accelerated in a spiralling and cumulative cognition-culture feedback loop.

Additionally, when we are able to project ourselves and others into the same frame of reference, and can also project more abstract symbolic units into this coordinate system, it follows that along and co-evolving with these other changes a capacity

(5) for projecting ourselves and others backwards or forwards into past and future situations is probable to have evolved, that is, a capacity for mental time travel, including the ability to retrieve and re-live episodic memories of past autobiographical events (Tulving 2005) as well as prospective foresight enabling the planning of future actions and events (Suddendorf & Corballis 2007).

Given the amazing experimental results with birds and great apes it is still quite a contentious topic to what extent the capacities for episodic memory and prospective foresight are uniquely human, but it seems clear that the human mental time travel system exceeds that of other animals in terms of flexibility and depth (Suddendorf & Corballis 2007).

Finally, these changes were certainly accompanied co-evolutionary by a means of externalising shared proto-concepts and communicatively coordinating cooperative activities in a flexible manner via the vocal and gestural level. (Hurford 2007, Tomasello 2008). At some time, concepts became public, that is “they became the sorts of things that lots of people can, and do, share” (Fodor 1998: 28).

It is conceivable that “building upon pre-existing representational schemes in animals” (Hurford 2007: 140), and a general perceptual and cognitive machinery that scaffolded them (Jackendoff 2007: 388), ever increasing linguistic abilities and concepts evolved step by step. They probably did evolve from the proto-concepts we can see in the higher mammals of today into the pre-linguistic concepts that are argued to exist in some of the other great apes (especially those individuals who are enculturated and symbol-trained) and then into some form of proto-language (Bickerton 2009). At some time, this proto-language with already quite sophisticated conceptual representations then evolved into the fully human language we know today.

The Human Faculty of Language

In summary, a truly human language faculty evolved, which involves, but is not limited to

(6) a collection of unique mental structures – phonology (externalisation) and syntax (merging constituents (A + B = [AB]) and creating blended new ‘mental building blocks’ which can be merged with other constituents recursively [AB] + C = [ABC]) – and the interfaces between these mental structures and the conceptual system. These “specific unique building blocks for phonology, syntax, and their connection to concepts” are what makes language and language acquisition possible (Jackendoff 2007: 388f.).

This account of course has not mentioned important ecological factors (e.g. navigation, foraging, predator avoidance) that will have contributed to these developments and constructed niches in which these factors could develop further and faster. In the case of language, for example both “fast processing and mapping from hierarchical structure to temporal ordering,” which are two fundamentally important features of human language,

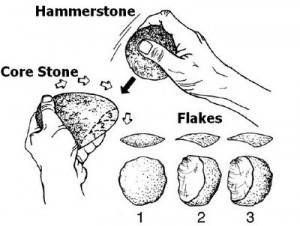

“can be attributed to progresses in the timing of actions necessary for producing and using hand axes, [as well as throwing] that is, to sensomotoric skills that could have been adapted for language” (Wunderlich 2006).

Support for this “action syntax” thesis comes from the fact that PET scans have shown that there is neural circuitry supporting and involved in both language production and early stone age tool-making (Stout et al. 2008, see also here and here).

It also fits with our general model that there is mounting evidence

“that much temporally sequenced hierarchical structure is constructed by the same part of the brain […] whether the material being assembled is language, dance, hand movements, or music (Jackendoff 2007: 388).

Additional work on mirror neurons, motor neurons that activate both when an action is performed and observed (Rizzolatti & Craighero 2004), points in the direction that they are involved in understanding the goal-related actions of others in a social context. The evolution of a Mirror Neuron System for understanding actions and intentions may have been a crucial part of the cognitive development that made human thinking possible (but see here, and here, for criticism of the idea that mirror neurons play an important part in language and action understanding).

This is also supported by the fact that the human conceptual system has two distinctive properties: One the one hand it enables abstract, relational, role-governed, symbolic thinking (Penn et al. 2008). But at the same time human concepts are still deeply rooted in, based on, and grounded in embodied sensori-motor experience (Barsalou 1999, Gallese & Lakoff 2005). This holds even for linguistic concepts and metaphors, which have been shown to be partly grounded in embodied cognition (Lakoff & Johnson 1980). To get back to language, a final indicator of the connectedness of social interaction and parts of higher-order cognition comes from proposals that “neural circuits doing computations to control the hierarchy of goal-related actions were ‘exploited’ to serve the newly acquired function of language syntax” (Gallese 2007: 666).

What makes Language Special?

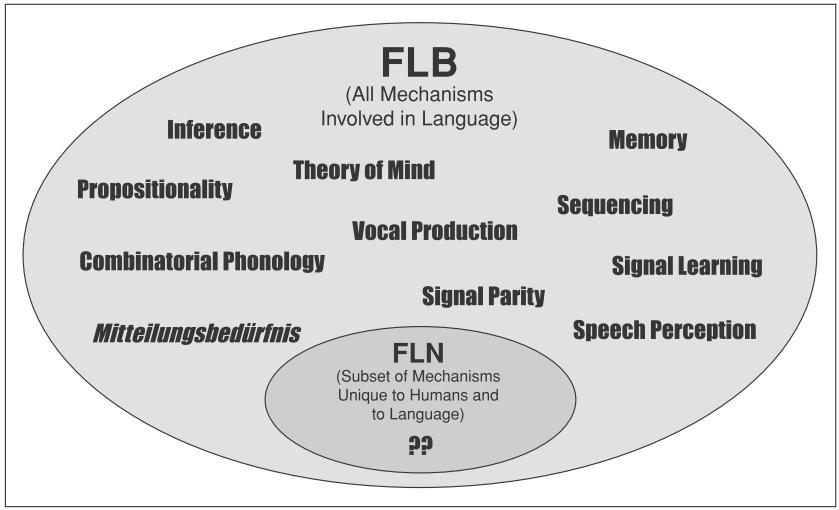

One of the things that seem to make language special, after all, then is, that the Faculty of Language conceived in a Broad Sense (FLB) is a multi-component system that involves and integrates many different cognitive mechanisms. There may also be a subset of mechanisms that are unique to language and constitute the Faculty of Language in the Narrow Sense (FLN), but this subset may also be empty.

In fact, one of the key commitments of Cognitive Linguistics is that our capacity for and knowledge of language emerge from a common set of human cognitive abilities and principles upon which they draw. On this view, language and its various aspects should be related to independently assessed cognitive principles and processes instead of reflecting cognitive principles only specific to language (Evans & Wood 2006: 40f.).

It has been proposed that it is this multi-component nature of language is exactly that makes it special.

“For example, Merlin Donald argues that language is “executive,” in the sense of dominating, controlling, and unifying other aspects of cognition, and that it is precisely the power of language to “reach into” any aspect of cognition that gives it its power, sharply differentiating human language from other animal communication systems which have limited semantic scope (Donald, 1991).” (Fitch 2010: 82)

Developmental psychologist Elizabeth Spelke – contra Tomasello – concurs with this view, arguing that it is the “innate, species-specific combinatorial capacity expressed in natural language,” that makes human cognition unique (Spelke 2009: 170f.).

“On this rival view, there are no uniquely human core systems in any substantive domain of cognition, including the domain of social reasoning. Only language has uniquely human core foundations, and it serves to represent and express concepts within and across all knowledge domains (Spelke 2009: 165)”

Now that we have some theoretical proposals on crucial aspects of human uniqueness (although this list is far from being definitive and exhaustive), we can see to what extent they are borne out by the comparative and developmental data that is available. I’ll have a look at some of these data in my next post on human uniqueness.

References:

Aitchison, Jean. 1998. The Articulate Mammal. An Introduction to Psycholinguistics. London / New York: Routledge.

Barsalou, Lawrence W. 1999. “Perceptual Symbol Systems.”Behavioral and Brain Scienes 22.4: 577–609.

Bickerton, Derek (2009): Adams Tongue: How Humans Made Language. How Language Made Humans. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bühler, Karl (1934): Sprachtheorie: Die Darstellungsfunktion der Sprache. Stuttgart: Fischer.

Carruthers, Peter (2002), The cognitive functions of language, in: Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 25 (6), 657–726.

Cassirer, Ernst (2006): An Essay on Man: An Introduction to a Philosophy of Human Culture. Hrsg. v. Maureen Lukay. Hamburg: Meiner (Gesammelte Werke. Hamburger Ausgabe. Band 23).

Cheney, Dorothy L. and Robert M. Seyfarth. (2007) Baboon Metaphysics: The Evolution of a Social Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Clark, Herbert (1996): Use of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Deacon, Terrence William (1997). The Symbolic Species. The Co-evolution of Language and the Brain. New York / London: W.W. Norton.

Donald, Merlin. (1991). Origins of the Modern Mind. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Dunbar, R. I. M. and Susanne Shultz. (2007)“Evolution in the Social Brain” Science 317: 1344-1347

Evans, Vyvyan and Melanie Green (2006): Cognitive Linguistics: An Introduction. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Fauconnier, Gilles and Mark Turner (2002) The Way We Think: Conceptual Blending and the Mind’s Hidden Complexities. New York: Basic Books.

Fitch, W. Tecumseh (2010): The Evolution of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Fodor, Jerry A. (1998) Concepts. Where Cognitive Science Went Wrong. Oxford Congitive Science Series. Oxford: Clarendon.

Gallese, Vittorio (2007). Before and below ‘theory of mind’: Embodied simulation and the neural correlates of social cognition.Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B-Biological Sciences 362 (1480):659-669

Gallese Vittorio, Lakoff George (2005) The Brain’s Concepts: The Role of the Sensory-Motor System in Reason and Language. Cognitive Neuropsychology, , 22:455-479

Graumann, Carl F. (2002): Explicit and Implicit Perspectivity. In: Carl F. Graumann und Werner Kallmeyer (Eds): Perspective and Perspectivation in Discourse. Amsterdam, Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company, 25-40.

Harder, Peter (fc) Conceptual construal and social construction .

Høgh-Olesen,Henrik. (2010): “Human Nature: A Comparative Overview.”Journal of Cognition and Culture 10.1-2, 59-84.

Hurford, James M. (2007): The Origins of Meaning: Language in the Light of Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jackendoff, R. (2007). Linguistics in Cognitive Science: The state of the art The Linguistic Review, 24 (4), 347-401 DOI: 10.1515/TLR.2007.014

Lakoff, George, and Mark Johnson (1980) Metaphors we live by.Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Lewin, Roger (2005): Human Evolution: An Illustrated Introduction. Oxford: Blackwell.

Moll H, & Tomasello M (2007). Cooperation and human cognition: the Vygotskian intelligence hypothesis. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences, 362 (1480), 639-48 PMID: 17296598

Penn, D., Holyoak, K., & Povinelli, D. (2008). Darwin’s mistake: Explaining the discontinuity between human and nonhuman minds Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31 (02) DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X08003543

Premack, David und Guy Woodruff (1978): Does the Chimpanzee have a Theory of Mind? In: Behavioral and Bran Sciences 1: 515-526.

Reader, S.M. and K.N. Laland. 2002. “Social Intelligence, innovation, and enhanced brain size in primates” PNAS 99: 4436-4441.

Rizzolatti, Giacomo and Laila Craighero. “The Mirror-Neuron System.” Annual Review of Neuroscience 27 (2004): 169–192.

Searle, John R. (1995): The Construction of Social Reality. New York: Free Press.

Spelke, Elizabeth S. (2009): ‘Forum.’ In: Michael Tomasello: Why We Cooperate. Cambridge, MA: Bost Review., 149-172.

Sperber, Dan and Deirdre, Wilson (1995): Relevance: Communication and Cognition. Second Edition. Malden et al.: Blackwell.

Suddendorf, T., & Corballis, M. (2007). The evolution of foresight: What is mental time travel, and is it unique to humans? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 30 (03) DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X07001975

Sterelny, Kim (2003): Thought in a Hostile World: The Evolution of Human Cognition. Malden u.a.: Blackwell.

Stout D., N. Toth , K. Schick, and T. Chaminade (2008): Neural correlates of Early Stone Age toolmaking: technology, language and cognition in human evolution. Proclamations of the Royal Society of London B: Biological. Sciences 363(1499): 1939-49.

Tomasello, Michael (2003): Constructing A Language. A Usage-Based Approach. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London, England: Harvard University Press.

Tomasello, Michael (2008): The Origins of Human Communication. Cambridge, MA; London, England: MIT Press.

Tomasello M, Carpenter M, Call J, Behne T, & Moll H (2005). Understanding and sharing intentions: the origins of cultural cognition. The Behavioral and brain sciences, 28 (5) PMID: 16262930

Tuomela, Raimo (2007): The Philosophy of Sociality: From A Shared Point of View. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Quine, Willard van Orman (1960): Word and Object.Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Verhagen, Arie (2007): Construal and Perspectivization. In: Dirk Geeraerts and Herbert Cuyckens (eds.) The Oxford Handbook of Cognitive Linguistics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wunderlich, Dieter (2006): “What forced syntax to emerge?” In H.-M. Gärtner et al. (eds.) Between 40 and 60 puzzles for Krifka. ZAS Berlin.

Man is the only animal that can initiate and use fire