James and I have a new paper out in PLOS ONE where we demonstrate a whole host of unexpected correlations between cultural features. These include acacia trees and linguistic tone, morphology and siestas, and traffic accidents and linguistic diversity.

We hope it will be a touchstone for discussing the problems with analysing cross-cultural statistics, and a warning not to take all correlations at face value. It’s becoming increasingly important to understand these issues, both for researchers as more data becomes available, and for the general public as they read more about these kinds of study in the media (e.g. recent coverage in National Geographic, the BBC and TED). But why are the public fascinated with these findings? Here’s my guess:

People are always intrigued by stories of scientific discovery. From Mary Anning‘s discovery of a fossilised ichthyosaur when she was just 12 years old, to Fleming’s accidental production of penicilin to Newton’s apple, it’s tempting to think that anyone could trip over a major breakthrough that is out there just waiting to be found. This is perhaps why there has been so much media interest recently in studies which show surprising statistical links between cultural features such as chocolate consumption and Nobel laureates, future tense and economic decisions, linguistic gender and power or geography and phoneme inventory.

Caleb Everett, who recently discovered a link between altitude and the use of ejective sounds, describes his discovery in these terms:

Everett recalled being shocked by his discovery. “I remember stepping out from my desk and saying, ‘Okay, this is kind of crazy,'” he said. “My first question was, How had we not noticed this?”

That is, we live in an age when there is more data available than ever before, it’s more widely available and there are better tools to do analyses. Anyone with an ordinary laptop and access to the internet could make these discoveries. Indeed, we’ve uncovered many unexpected correlations at Replicated Typo. However, just as Anning’s discoveries were made as the theory of biological evolution was still developing, the ability to detect correlations in cultural features is outstripping the understanding of how to assess these findings. Early reconstructions of fossils included a lot of errors, some of which have been difficult to redress in the public’s mind. Without a good understanding of cultural evolution, similar mistakes might be made during the current race to find statistical links in our field.

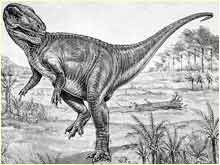

An early reconstruction of Megalosaurus by Richard Owen, based on limited evidence and theory, compared with the modern reconstruction source

Everyone knows that correlation does not imply causation, but there are other problems inherent in studies of cultural features. One problem that is often discounted in these kinds of study is the historical relationship between cultures. Cultural features tend to diffuse in bundles, inflating the apparent links between causally unrelated features. This means that it’s not a good idea to count cultures or languages as independent from each other. Here’s an example: Suppose we look at a group of highschool students and wonder whether the colour of their t-shirts correlates with the kind of food they bring for lunch. We survey 10 children, and see that 5 wear red t-shirts and eat peanut-butter sandwiches. This appears to be strong evidence for a link, but then we see that these 5 pupils come from the same family. There’s now a better explanation for the trend – the children from the same family tend to have the same choice of clothes and are given the same lunch by their parents. The same problem exists for languages. Languages in the same historical families, like English and German, tend to have inherited the same bundles of linguistic features. For this reason, it can be quite complicated to work out whether there really are causal links between cultural properties.

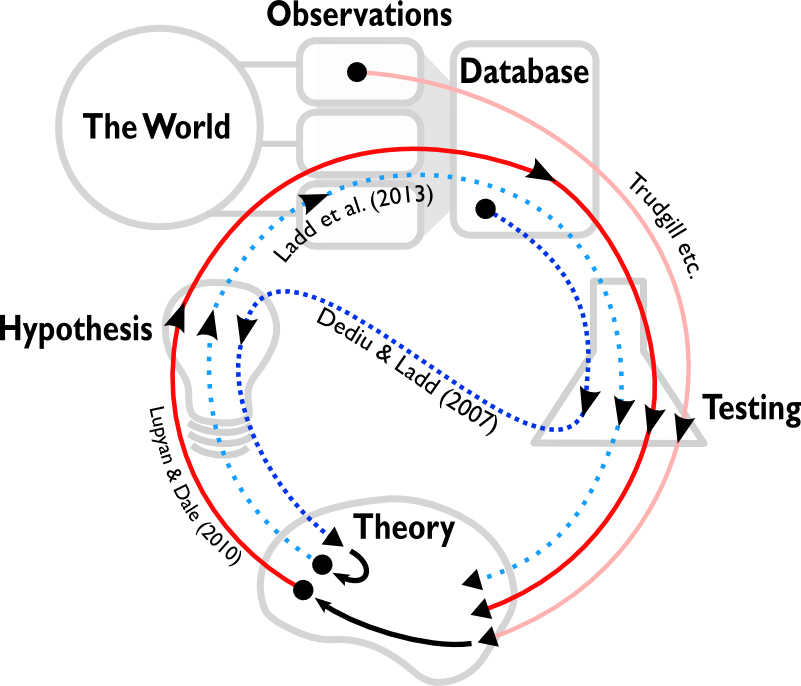

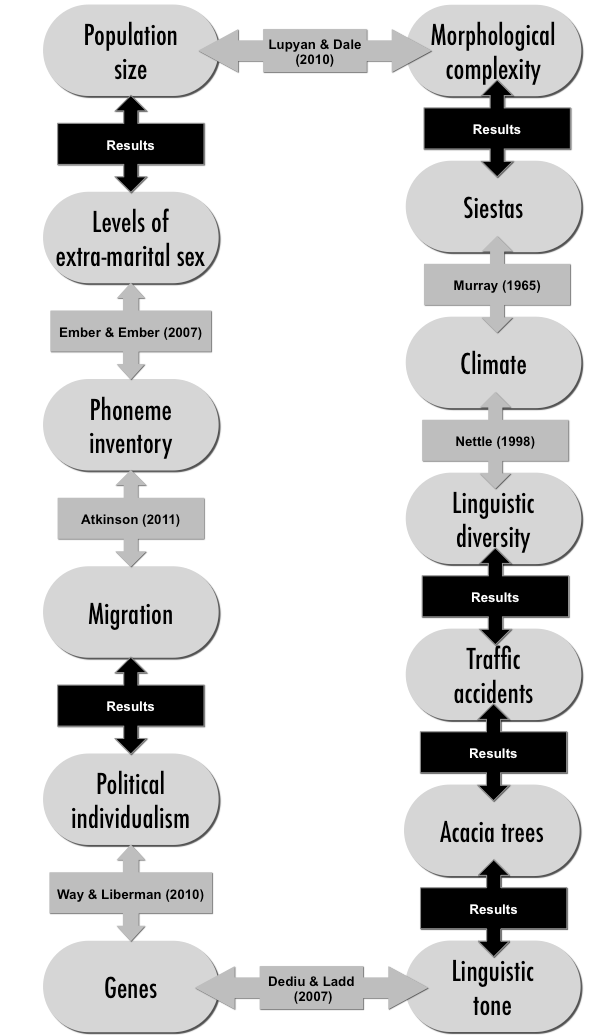

Our paper tries to demonstrate the importance of controlling for this problem by pointing out a chain of statistically significant links, some of which are unlikely to be causal. The diagram below shows the links, those marked with ‘Results’ are links that we’ve discovered and demonstrate in the paper.

For instance, linguistic diversity is correlated with the number of traffic accidents in a country, even controlling for population size, population density, GDP and latitude. While there may be hidden causes, such as state cohesion, it would be a mistake to take this as evidence that linguistic diversity caused traffic accidents.

In the paper we suggest that correlation studies should demonstrate at least two things:

- That the hypothesised correlation is stronger than correlations between similar cultural features that are not expected to be linked.

- That the hypothesised correlation is robust against controlling for cultural descent.

We discuss some methods for achieving this, and demonstrate that they can debunk the spurious correlations that we discover in the first section. Many of these methods are straightforward and can be done quickly, so there’s no excuse for avoiding them.

As well as careful statistical controls, correlation studies can also be assessed based on whether they are motivated by prior theory or not. For example, Lupyan & Dale’s (2010) demonstration of a correlation between population size and morphological complexity was motivated by a long line of research on languages in contact. However, both kinds of discovery can be useful if they are seen in the context of a wider scientific method. We argue that correlation studies should be viewed as explorations of data, and as a sort of feasibility study for further, experimental, research. For example, the chance discovery of a link between genes and tone by Dediu & Ladd was not only statistically well controlled, but was used as the inspiration for more detailed laboratory experiments, rather than being seen as proof in itself.

Coming across statistical patterns by chance has always been part of the scientific process. However, with culture, it’s much more difficult to intuitively distinguish real patterns from noise or historical influence. Correlations between unexpected features will continue to be exciting, but researchers should apply the right controls and see the studies as motivational rather than direct tests of hypotheses.

Roberts, S. & Winters, J. (2013). Linguistic Diversity and Traffic Accidents: Lessons from Statistical Studies of Cultural Traits. PLOS ONE, 8 (8) e70902 : doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070902

Glad the paper’s out so I can cite.

BTW, I believe it was Dan’s son, Caleb, that did the paper on ejectives, not Dan himself…

Agh! I knew that. I shouldn’t have put his name in an embedded sentence. I’ve edited it – thanks!

Glad you like the paper, please cite away!

Lovely. We are seeing more circling the wagons around this kind of thing now that the social sciences are maturing into more sophisticated use of statistics, and getting spanked soundly here and there for abuses. Your latter point, that correlation is a bare beginning to specifying good questions, is a wonderful downsizing of expectation and elevation of precision. It’s also a reminder of the coming interdependency of good science, and the coming decrease of the half-life of bad and partial science. As a professional consumer of scientific output, it’s critical to hear more and more of this, to keep me from running and twirling in song across fields that I should be traversing on my hands and knees.

One interesting implication for me is how correlation studies lurch hereby to be on more of an even footing with qualitative research, as a different way of finding good questions and specifying research well, through clarifying dimensionality. That seems right. Otherwise, we’re not even getting through the pertinent dumb questions, let alone the subtle stuff. It’s another way to be close enough to feel tendencies arising up through one’s boots, and should in similar fashion be reserved when asserting causation.

When people despair at the ineffable nature of the social sciences, or, worse, when they assume it, they’re bemoaning nonlinearity, hidden dimensions, or the existence of more than two or three variables to a problem. There are Mongol hordes of findings awaiting us at the early fringes of nonlinearity and relatively low dimensionality that I’m very excited about getting traction on as we sort out our modern relationship to data and statistics. Your paper is a giant early step in that direction. Well done! And thanks for publishing on PLOS ONE.

Hey Sean,

The paper looks interesting and I will certainly cite it in future work related to geographic-phonetic correlates. I thought I’d make a couple of relevant points. First, with respect to the “discovery” quote above, the context of the quote (in the interview itself) was that I had just mentioned to the reporter how I had predicted the ejectives-altitude correlation, based on some basic math and Boyle’s law. In the light of that prediction, I went looking for the correlation and was still honestly quite surprised to find the extensive evidence for it. So I did find it remarkable that the correlation hadn’t been noticed before, in the light of the basic physical modeling. (That’s not to say that the air compression principles alone motivate the correlation, but they were sufficient to warrant a crosslinguistic examination such as the one I undertook.) The second point I want to make is that there is a fairly robust literature in medical research demonstrating influences of ambient air conditions on the respiratory and vocal tracts. So it is far from difficult to see how geographic conditions could in theory impact predilections for particular sound patterns. In fact, I would argue that grouping geographic-phonetic correlations with some of the patently spurious ones you mention is a bit disingenuous. (I make a similar point in a recent interview with Slate’s Lexicon Valley program.) Inter alia, the nature of such correlations is open to direct investigation via myriad experimental paradigms.

I should also add that there are a variety of very diverse reasons that this sort of work draws attention from the media–I think you grossly oversimplify the matter above. Having spoken to many reporters after the publication of my study, I have plenty of thoughts on the matter and am happy to share them. Email if interested.

All the best, Caleb

Hi, Thanks for this – it’s good to have the context of the quote. I still think it captures what many readers think about these studies, but I’d love to hear your take. As I pointed out in my other post, your study is slightly different from many of the ones we discuss in our paper because it has a much more concrete mechanism that predicts the change. It therefore falls with the pre-motivated studies, which we see as useful in kick-starting the conventional scientific process, which is more experiment-orientated. I’m looking forwards to more work on your theory!