Does the weather effect the languages we speak?

This week, Caleb Everett, Damian Blasi and I have a paper out in PNAS (also available here) on the effects of humidity on the production and perception of lexical tone, and the subsequent predictions about the distribution of tone across the world.

The basic principle behind studies of cultural evolution is that a selective pressure on communication can transform the structures of a language over time. What we explore is whether speaking in dry environments exerts a pressure to avoid using sounds that are more difficult to produce or comprehend, leading to those sounds being selected against.

Edit: See also this FAQ page

This isn’t exactly a new idea. There have been previous studies linking the sonority of a language’s phoneme inventory to climate variables, based on similar principles (here and here), and more recently, Caleb Everett looked at ejectives and altitude (which we’ve previously reviewed). However, our study uses a much larger sample than previous studies, and has stricter controls for genealogical and areal relationships.

The first part of our paper reviews a basic finding from various experiments: inhaling dry air dries out the vocal folds, leading to adverse effects in articulation, specifically aspects of phonation that are important for careful control of pitch. That is, in dry environments, distinctions in pitch come under a selective pressure.

To review tone: all languages use differences in pitch to communicate. In English, you can raise the pitch at the end of a sentence to turn a statement into a question or to highlight particular words in a sentence. However, it’s easy to communicate in English without using pitch – you could still understand someone if they didn’t vary the ‘notes’ in their sentence and spoke in a monotone like a robot. However, pitch is much more important in some languages, like Mandarin, where changing the pitch of a word can completely change its meaning. For example, ‘ma’ spoken with a level pitch means ‘mother’, while ‘ma’ spoken with a falling then rising pitch would mean ‘horse’. Languages with contrasts between two types of tone are described as ‘simple’ tone languages, and those with more distinctions are described as ‘complex’ (the largest number of distinctions coded in our database is 12).

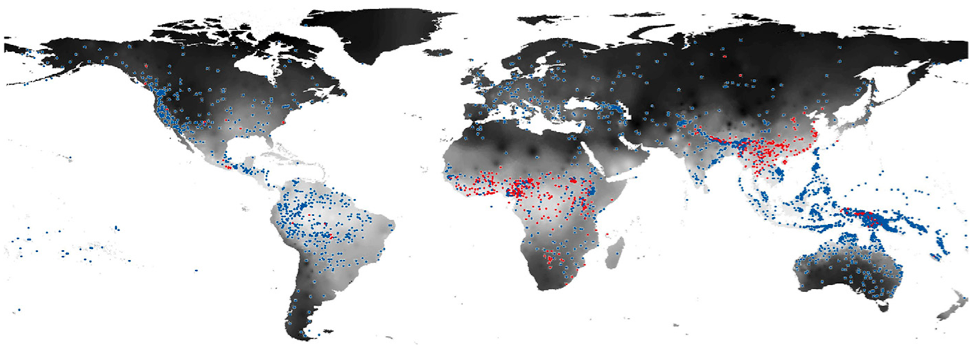

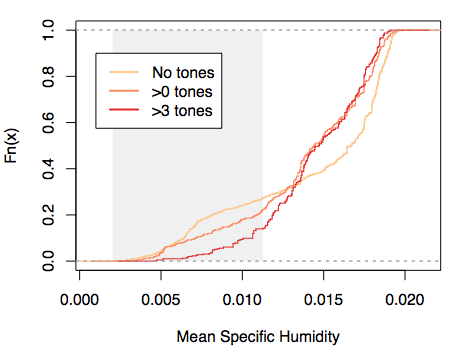

The main result in our paper is that there is a difference in the distribution of tonal and non-tonal languages according to climatic factors like average humidity: complex tonal languages are rare in dry places. The graph below shows the empirical distribution of different types of language (in the paper we show the graph from the WALS data, but the graph below is from ANU data, which we use in the monte-carlo analysis):

Each curve starts at the bottom left and increases each time we observe a language at the given humidity, until we’ve observed all languages at the top right. We can see that we’re less likely to observe languages with many contrastive tones in regions with lower humidity (the shaded section shows the lower quartile of humidity).

However, demonstrating this statistically wasn’t straightforward. Note that the prediction is that there’s a selective pressure against tone in dry environments – it doesn’t make any prediction about the distributions in humid climates. That is, it’s a uni-directional implication (discussed in a previous post). In this case, a simple regression approach is not suitable. Furthermore, the languages in our data are related historically, potentially inflating the correlation. We’ve written extensively on spurious correlations, but we’d like to point out that, in this case, we have a plausible mechanism which makes a concrete prediction.

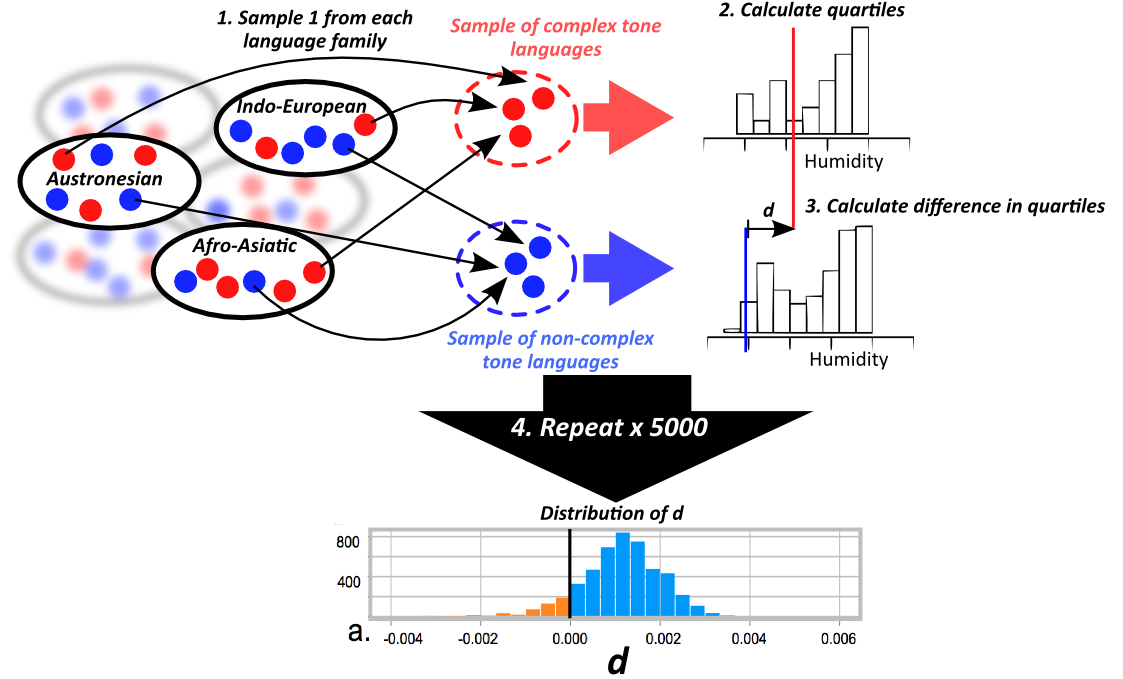

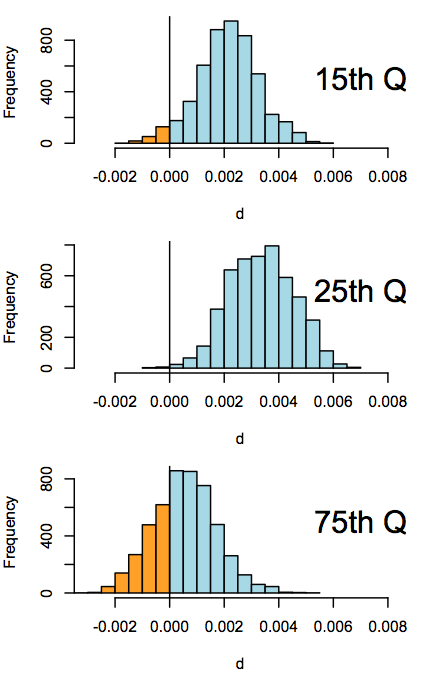

Damián’s ingenious solution was a Monte Carlo test, as illustrated below. First, we take a random sample of languages with complex tone – one from each language family, so we know they are independent. We look at the distribution of humidity for this sample, and work out the 15th percentile – the point below which 15% of the languages are fall in the distribution. We then do the same for a sample of languages without complex tone. We can compare the difference in 15th percentile values for the two distributions of humidity – let’s call this d. The prediction is that the complex-tone languages will have a higher 15th percentile than the non-complex-tone languages. So we run this procedure many times, and come up with a distribution of d values. We predict that the majority of values of d will be positive (distribution of complex tone languages is shifted to the right).

And indeed, that’s what we found: there were differences in the climatic distributions of tonal and non-tonal languages in dry regions, but less so for more humid regions.

We also ran the same tests, but selecting languages by geographic region instead of language family, in order to demonstrate the results are not due to contact or borrowing (regions were defined according to Autotyp region, designed to reflect areas of linguistic contact). Again, we find that there are differences in drier regions, but not more humid regions (for humidity, proportion of samples where d is positive: 15th quantile: 96%; 25th quantile: 99%; 75th quantile: 68%).

I also ran a serendipity check with the WALS data (although we have a prior motivating hypothesis, so we don’t report this in the paper). I ran a chi squared test comparing the distribution of tone types against whether the language is in the driest 25th percentile of MAT (chi squred = 46.7, df = 2, p < 0.0001):

| WALS tone | Humidity 1st quartile (driest) | Humidity 2-4th quartile |

| No tones | 109 | 198 |

| Simpe tone | 20 | 112 |

| Complex tone | 3 | 85 |

Then I did the same for every variable in WALS. Humidity had a stronger relationship with tone than with 96% of variables (with many of the top variables also being consistent with the overall theory). Of course, this doesn’t control for language family, but does indicate that the correlation is not spurious.

The paper and supporting information has a more detailed discussion of individual cases, and some more statistical checks.

So, it seems that there is reasonable support for the climate providing a selective pressure on the form of languages. Crucially, this selective pressure is present because of communicative needs – ease of production and comprehension. That is, this pressure can apply because the ‘ecology’ of language is use in interaction.

We could extend the idea of cultural selection further to suggest that one aspect of a language (tonal or non-tonal) can itself provide a knock-on selective pressure for other aspects of language. Recently, I did some work with Francisco Torreira and Harald Hammarström showing just this: linguists have argued that lexical tone and phrase-level intonation compete for the same linguistic resource (pitch), and we showed that languages with lexical tone are less likely to use intonation to distinguish questions versus statements.

Many studies of cultural evolution focus on cognitive selective pressures (e.g. processing, memory, frequency etc.), which are usually assumed to apply universally. The current study suggests that some pressures may not be universal, but only apply in particular situations. This adds to the literature on niche-specific cultural evolution, such as the effect of population size on morphological complexity, or demography on phoneme inventory.

The link between climate and language is still tentative, and we’re planning a series of follow-up studies. Still, it opens up the possibility for a field of ‘Geophonetics’.

Everett, Blasi, Roberts (2015) Climate, vocal folds, and tonal languages: Connecting the physiological and geographic dots. PNAS, pdf

Interesting article and I applaud the effort you put it – it’s quite well done.

This seems to betray a lack of knowledge about what ‘tone” is, however. Tone is not simply about a language’s use of pitch modulation – all languages use pitch. Rather it’s simply about tone’s use *lexically*. As far as I’ve seen, tone languages do not vary pitch more than non-tone languages, rather it’s the function of pitch that differentiates tone from non-tone languages.

So, that seems to subvert the entirety of the premise.

Your thoughts are appreciated.

Hi, thanks for your comment – and it’s a point I make in the blog post above. The general hypothesis is not specifically about tone/non-tone, but about acoustic properties that affect, amongst other things, the aspects of sound that go into careful control of pitch. It’s true that I’m not an expert on tone, but surely the function of pitch in a tonal language is more fundamentally important than pitch in a non-tone language? Indeed, one of the studies we cite in the article finds that speakers of a tone language who sufferer from muscle tension disphonia, which has similar effects to dehydrated vocal chords (and can be caused by dry air), have more trouble producing and being understood than speakers of non-tone languages. Of course, this could be tested more carefully, and we have some follow-up experiments planned.

You wrote: “the function of pitch in a tonal language is more fundamentally important than pitch in a non-tone language”

This is not, in fact, true, unless you define “important” as relating to lexical access alone, as opposed to overall speech communication. Pragmatics, information structure, and syntactic parsing are communicated via pitch in non-tonal languages, for example.

I should also point out that tone and f0 modulation are not isomorphic either and there are lots of acoustic parameters that go into tone production and perception.

I agree that pragmatics and overall communication is the key to linking the physiological effects of climate to the evolution of a language. But would you say that e.g. question intonation requires more precision and more intense modulation of pitch (and other aspects) than lexical tone? I would be very interested in research that compared different domains of language in terms of how degradation affects overall communication. I know Marisa Casillas’ work showing that children pay attention to both sentence-level prosody and lexical content of utterances in learning (http://pubman.mpdl.mpg.de/pubman/item/escidoc:1796081:8/component/escidoc:1796082/CasillasFrank13.pdf).

further – the general point of the paper is that differences in climate put different selection pressures on the way a language uses sounds. We show there’s a correlation with lexical tone, but I’d be quite happy if it turned out that this was just a proxy for a the real effects. In the post above, I mention the work on sonority, and tone is correlated with use of intonation to mark interrogatives.

“would you say that e.g. question intonation requires more precision and more intense modulation of pitch (and other aspects) than lexical tone?”

No one’s shown this to be the case, and I’d suggest that it is a common misconception about tone among folks at journals like PNAS (who also published the Dediu and Ladd paper) that any phonetics/phonology journal would catch.

Sonorous segments (codas) are more likely to be tone bearing units. That should be factored in and controlled for.

Nice post Sean. Perhaps the key distinguishing characteristic of this work, in addition to the more careful genealogical and areal controls (when contrasted to previous work on the broad topic, including my own), is that we predict the patterns based on so much work in laryngology.

Marc, thanks for your interest. I’m guessing you haven’t taken a look at the actual paper yet, since we address some of those points (and, not surprisingly, they were brought out during the review process though I had them in mind early on). If you want to talk more about the points, feel free to contact me via email. Your view that pitch modulation is somehow not more precise in tonal languages (overall) is a non-starter to me for several reasons despite the well-known existence of complex f0 modulation in non-tonal ones. But I’m happy to discuss after you’ve taken a look at the laryngology data we survey.

Oh, and re our choice to publish in PNAS: The advantages are pretty substantial, and rest assured prominent phoneticians have read this work.

Best, Caleb

(See Caleb’s reply below). We’ll be investigating the overall hypothesis in segment inventories very soon.

Thanks for this write-up! I found the paper really interesting, although there are large bits of it that I’m not at all competent to judge (like the whole evolutionary and computational bit – the discussion in the post was really helpful!). I did have some misgivings about how one defines a ‘tone language’, so I took a random sample of languages I have some familiarity with. I found the results a bit surprising, so I wrote up a little post about it (it’s a bit long for a comment, sorry!): http://blog.anghyflawn.net/2015/01/21/humidity-causes-complex-tones/. I do hope this doesn’t come across as a ‘get off my turf!’ kind of comment (I know some linguists are guilty of this), and I’m sure that the results do not hinge on this in any particularly crucial way. But it’s still something to consider.

I did, in fact, read the paper and if you recall, you assert, without references, that “languages with phonemic tone necessitate voicing at relatively precise pitches throughout an individual’s normal range.”

This has *not* been shown to be the case, relative to non-tone languages. So no, you do not address this issue and it was not brought out during review.

You write here that you consider that a non-starter, but I, and colleagues, consider this the crux of the matter. This type of oversight is a problem in this paper and others like it (e.g, Keith Chen’s work), that seek to establish a relationship between language and environment or language and other cognitive factors with only a cursory understanding of the linguistic property at hand. This is not only evident through the point above, but also through the omission of any discussion (or even mention) of pitch-accent languages and minimal discussion of the phonetic correlates of tone (a passing reference to phonation).

Sean Roberts’s excellent work at this site has done an exemplary job of highlighting the file-drawer problem for precisely this sort of correlational work. PNAS is precisely the type of journal where the file-drawer problem is endemic. While the substantial advantage of greater press coverage or impact factor may have motivated your choice of journal, it only exacerbates concerns about cherry-picking.

Ultimately, I am sympathetic to the research program — I worked in Patrick Wong’s lab for 3 years and have published on this sort of stuff — but I see a glaring hole here. Tackling mechanism is certainly the way to go, but the bridge you build only goes halfway there.

The point of post-publication review and discussion (blogs, reddit, open access journals etc) is to bring these issues to the fore for those that might not be experts on a paper’s details. So, I don’t see the point in discussing only over email.

I suggested email Marc ’cause it allows for deeper discussions and not surprisingly we can’t follow all of the blog postings about this sort of study, and allows for substantive long-term interaction. If you think next-day blog comments are the real loci for post-publication discussions of the work, then I’m probably not gonna make any headway anyhow. But I’ll quickly say a couple of things here: First, you’re not even referencing the part of the study I was discussing where we make the claim (given our little space to do so) why phonemic tone requires more precise pitch. Second, a series of phoneticians read this, including the editor at PNAS and others. It surprises me you’d think you’d be the first to raise such an obvious point, or that such a point only comes out post-publication. Finally, whatever your position on such issues, I just hope you and others interact with the laryngology data that simply goes without mention in the linguistic literature, and actually try to justify why phonology would somehow be impervious to ecological constraints in somehow unique way amongst the suite of human behaviors. To suggest that this is just “finding correlations” is just an oversimplification that does little to advance the discussion IMO. The correlation is a notable explanandum. But let’s discuss it in the light of the physiological data we cite at least.

Yes, I do believe open debate/discussion that others can be privy to is more fruitful than private email discussions. The substance of what I write would not be particularly different.

If you disagree, feel free not to reply.

Perhaps you thought you put something in your paper that didn’t make it in, or perhaps my reading comprehension is not up to snuff, but your paper does *not* show that tone language speakers require greater control over f0 than non-tone languages overall (as opposed to just lexically). In fact, the paper you cite, Keating & Kuo (2012) says precisely *the opposite*, that pitch variation in Mandarin speakers is about the same as English speakers, depending on type of speech.

So, please do me the favor of actually explaining how you consider that a non-starter instead of simply repeating that it’s in the paper. Feel free to cut and paste, which you could have done at the outset.

Interesting, and I’ll keep following this. One thing I’d like to comment on is the perhaps too-simplistic distinction between simple and complex tone systems, where “complex” is defined as “a system containing three or more pitch-based phonemic contrasts.” There can be quite a lot of complexity concealed by the label of “simple” tone. Example: Konni [kma] would be classified as simple, since it contrasts High and Low. However, there is also a downstepped High (!H), and on a single syllable, H and L can combine to form a LH rise, a HL fall, and a H!H fall. So what looks like a two-tone system has six phonetic realizations. Furthermore, a good number of the “complex” tone systems have tones that do not vary much. So the bifurcation into complex and simple tone, without further details, may not be helpful.

I’ll check it out when I get a chance, thanks.

Thanks Mike. Please note that, in the SI, we do not appeal to this simple distinction to avoid this sort of criticism. So we test the hypothesis simply against the number of contrastive tones, without looking at “complex” vs. “not” cases.

Hey Marc,

One of the issues with pursuing these things through ephemeral comment sections is it assumes the authors of visible studies can go from blog to blog catching up with discussions at the rate they move. It just doesn’t work and when I say I don’t have time to do so trust me I’m not being hyperbolic. Very quickly: I read Keating & Kuo, we’re not talking about *overall* pitch variation and I think you know we’re not. And the Vietnamese paper certainly did not “motivate the notion” as any reasonably close inspection of the paper suggests. It was used as ancillary support, reasonably I think.

On a more general note, do you really think that the laryngology data we survey so carefully should have no relationship to the production of tone? Really?

I do hope you do follow up work on the topic though, sincerely, critical or not. Then we can have more substantive follow-up. These interactions don’t constitute that IMO.

Wishing you the best with your work (that’s sincere, btw), Caleb

It’s true that for authors it is impossible to keep track of every thread, let alone respond coherently — things simply move too fast. Still, since this particular thread was opened by one of the authors of the study, it’s not weird for Marc to expect a good discussion here.

Have you considered a central FAQ covering the most common questions and objections? It’s simple enough thing to do and it can be a tremendous service to interested readers — linguists and lay people alike. We did this for our paper on the universality and significance of words like ‘huh?’: http://huh.ideophone.org/frequently-asked-questions/

Good idea Mark, maybe we’ll do that at some point. Presumably you waited awhile before posting that, though? I’d rather let the comments accrue rather than rushing to address all since they vary in quality and substance. But, again, point taken. Btw, enjoyed the ‘huh’ study.