According to the evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey Miller and his colleagues (e.g Miller 2000b), uniquely human cognitive behaviours such as musical and artistic ability and creativity, should be considered both deviant and special. This is because traditionally, evolutionary biologists have struggled to fathom exactly how such seemingly superfluous cerebral assets would have aided our survival. By the same token, they have observed that our linguistic powers are more advanced than seems necessary to merely get things done, our command of an expansive vocabulary and elaborate syntax allows us to express an almost limitless range of concepts and ideas above and beyond the immediate physical world. The question is: why bother to evolve something so complicated, if it wasn’t really all that useful?

Miller’s solution is that our most intriguing abilities, including language, have been shaped predominantly by sexual selection rather than natural selection, in the same way that large cumbersome ornaments, bright plumages and complex song have evolved in other animals. As one might expect then, Miller’s theory of language evolution has been hailed as a key alternative to the dominant view that language evolved because it conferred a distinct survival advantage to its users through improved communication (e.g. Pinker 2003). He believes that language evolved in response to strong sexual selection pressure for interesting and entertaining conversation because linguistic ability functioned as an honest indicator of general intelligence and underlying genetic quality; those who could demonstrate verbal competence enjoyed a high level of reproductive success and the subsequent perpetuation of their genes.

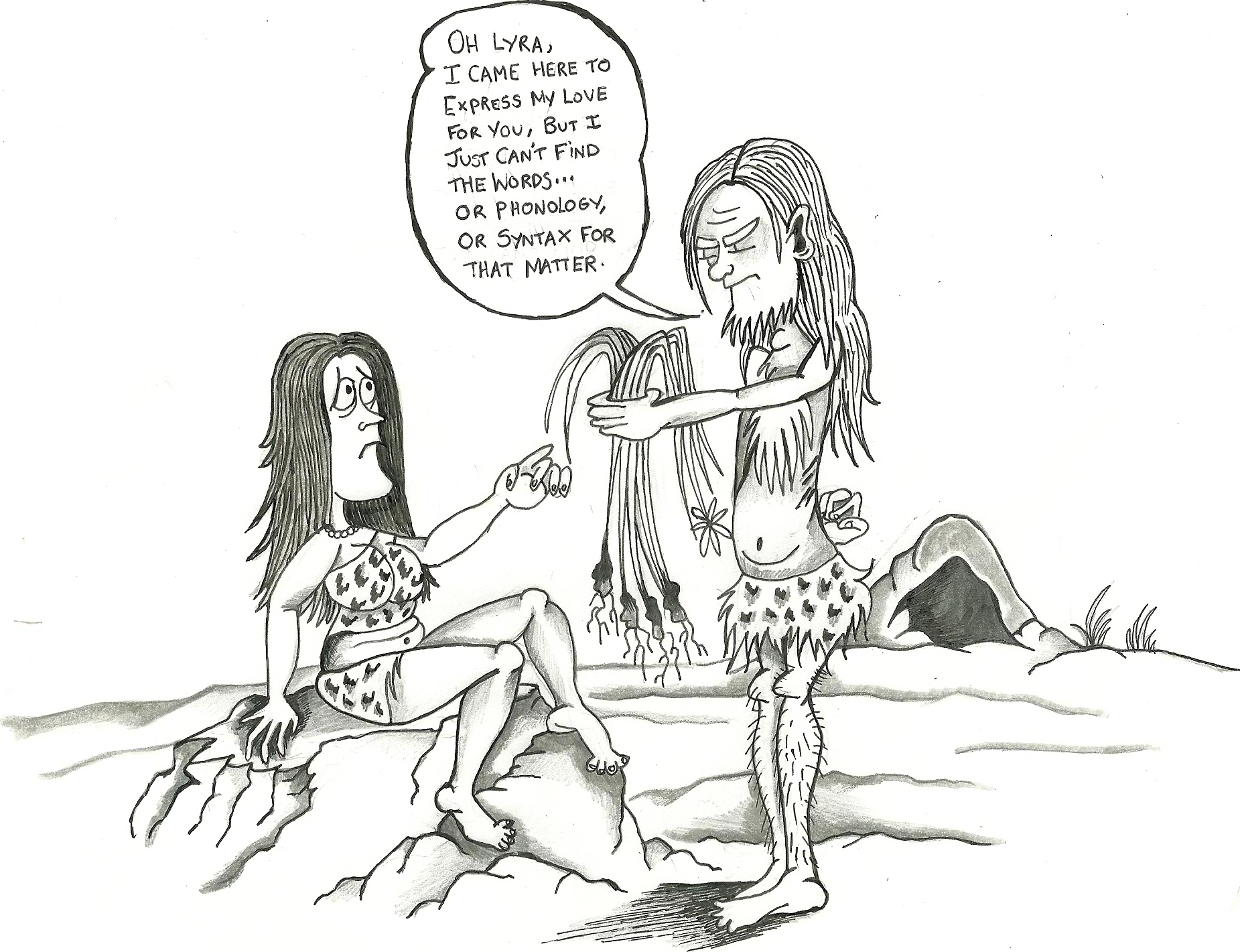

There are certainly aspects of the broader argument surrounding Miller’s idea that warrant exploration, such as the idea that linguistic competence may be influenced by genetic integrity – a topic I intend to discuss in future posts. Thus, it is perhaps unfortunate that romantic appeal renders this theory the type most vulnerable to popularisation and depictions of doe-eyed cavemen and women courting one another with prose rivalling Shakespeare and cadences comparable to Beethoven. But aside from the potential to conjure sickening visions of early Homo in love to mind, there’s a much more fundamental reason why Miller’s theory isn’t viable.

Linguists have long recognised that language is made up of up of a number of independent yet integrated components (prosody, phonology, morphology, syntax, morphosyntax and semantics), all of which are important in forming the effective communication system we use today. Following on from this, the position adopted by most evolutionary linguists is that language is therefore far too complex to have evolved spontaneously, but rather, that each linguistic component evolved separately, most likely in response to differing selection pressures and at different times in human evolutionary history (linguists refer to these intermediate stages as ‘protolanguage’), becoming integrated to form fully complex language with the advent of modern Homo sapiens.

From the viewpoint of most linguists then, Miller’s theory runs into a glaring paradox: Language could not have evolved primarily as a result of pressure for verbal creativity, because language would have to evolve to a substantially sophisticated degree beforehand in order for verbal creativity to be evaluated. For example, without an evolved capacity to produce distinct meaningless units of sound (the phonological capacity) there would be no opportunity for a species to develop the ability to recombine these sounds into the meaningful combinations that we call words. Miller’s theory still remains unrealistic even if conceptualised in the context of an ancestral population of rudimentary vocabulary users, because without the existence of syntactical rules with which to order words, it is unlikely that resulting stories would have encoded sufficient semantic weight to warrant assessment for entertainment or interest value.

Language and Music: Big Lumps of Behaviour?

It soon becomes clear that the key factor influencing the nature of Miller’s idea is his purely adaptationist approach to the study of language evolution, that is, he has focused exclusively on the possible reproductive and survival payoffs that language conferred and has purposefully ignored the importance of phylogenetic inquiry i.e. what language ‘looked like’ at successive stages of its evolution. In doing so, Miller explicitly rejects the conception of language as an entity of components, viewing this as an unnecessary abstraction that obscures functional analysis. By reducing language to a ‘big lump of behaviour’ Miller has inadvertently sent his theory spiraling into difficulty.

It is worth noting that Miller has applied this same rationale to the evolution of music (see Miller 2000a), but somewhat more successfully. There is a crucial reason for this. Like language, music can be conceived of as an integrated system of components (such as pitch, melody, rhythm etc.). However, as musical components are not semantically meaningful in the same sense that language components are, explaining the function of music (as conceived as a big lump of behaviour) without referring to intermediate evolutionary stages does not create the paradox encountered by the same approach to language, and not as much is compromised at the mercy of Miller’s parsimonious ideal.

Of course, the overriding issue here is not Miller’s enthusiasm in asserting the value of the adaptationist approach, but rather, his particular use of the adaptationist approach in isolation. With regards to a trait with such inherent complexity as language, the virtue of the adaptationist approach can be realised only in light of experimental data, comparative evidence from other species and most importantly, phylogenetic scrutiny.

References

Miller, G. F. (2000a) Evolution of Human Music Through Sexual Selection. In Wallin, N. L., Merker, B. (eds.) The Origins of Music. MIT Press pp.329-360.

Miller, G.F. (2000b) The Mating Mind: How Sexual Choice Shaped the Evolution of Human Nature. New York: Doubleday.

Pinker, S. (2003) Language as an Adaptation to the Cognitive Niche. In: Christiansen, M.H and Kirby, S (Eds.) Language Evolution (2003) Oxford: Oxford University Press. p.16-37.

Hi Anne, your post also calls to mind Dunbar’s idea that language could have served as a form of adapted social grooming for expanding group and brain size. I don’t know if Miller or Pinker’s ideas are soley focused on fitness displays or propositional instead of phatic aspects of language, but from what I vaguely recall Dunbar does have a chapter on it in Christiansen and Kirby’s book.

For example, without an evolved capacity to produce distinct meaningless units of sound (the phonological capacity) there would be no opportunity for a species to develop the ability to recombine these sounds into the meaningful combinations that we call words. Miller’s theory still remains unrealistic even if conceptualised in the context of an ancestral population of rudimentary vocabulary users, because without the existence of syntactical rules with which to order words, it is unlikely that resulting stories would have encoded sufficient semantic weight to warrant assessment for entertainment or interest value.

But this sounds so much like a creationist arguing “a bombardier beetle couldn’t have evolved because the catalases aren’t good for anything without the quinones and neither is worth it without the reaction chamber and something to spray it.” Just because it’s hard to imagine what good they’re worth alone doesn’t mean you can’t go out and find bombardier beetles that get along with no sprayer (they just foam) or no catalases (the quinones help harden the exoskeleton). Can’t you imagine humans that sexually select for the sound “d’oh!” or something and then other phonology proceeds from there?

I’m glad you’re posting about this — I liked Miller’s book a lot and was disappointed when I googled it to find not a whole lot of people explaining what might be wrong with it.

Hi Noumenon,

Haha, oh dear, that’s certainly not what I intended. I would never argue that only fully formed language is any good, so (for example) that vocabulary without syntax would be useless, but rather that language at the particular evolutionary stage that Miller inadvertently refers to would not be subject to the selection pressures or carry the function that he believes it would. As propositional meaning is so highly dependent on the linguistic components necessary to convey the message, you would think that for conversation to be entertaining or interesting, language would have to evolve to some degree of sophistication first in order to be assessed for this.

Maybe this is a matter of bad phrasing on mine or Miller’s part however, as of course, what we modern humans consider ‘interesting conversation’ is unlikely to be equivalent to what early Homo grappling with language would consider as such. So I suppose in that sense you’re right, in a population of rudimentary vocabulary users, the ability to say ‘d’oh!’ (for example) and other items of vocabulary may feasibly have functioned as an indicator of an individual’s fitness in some way and might have been sexually selected for – maybe a larger than average vocabulary could have served as a demonstration of memory capacity (and by extension, good brain, good genes), rather than the ability to produce what we might think of as interesting or entertaining conversation (and hence good brain, good genes), which would seemingly require a higher level of linguistic sophistication.

The other thing I must bring in here is comparative evidence from the communication systems of other animals. Many non-human primates emit loud calls which alert conspecifics to predators and food. They are often likened to human words because some argue that they ‘refer to something in the world.’ However, calls like these arise via natural selection not sexual selection, because they function as warning devices and preserve survival. In addition, such calls are not phonologically variable enough for recombination into novel calls or ‘vocabulary’ – which is possibly why great apes have smaller communicative repertoires than we would expect. On the other hand, we know that birds and non-human primates such as gibbons and geladas sing long phonologically complex (but ‘meaningless’) songs which are sexually selected. It is probable that early humans sang or uttered similar songs or ‘phrases’ and that such strings were later segregated into words (see the holistic theory of protolanguage). This would also suggest that sexual selection kicked off language evolution but also provides an explanation as to why our ancestors had such a rich, phonological inventory from which to create thousands of words. The problem is that because Miller does away with language as an integrated system of components he does not even consider these caveats.

So to conclude, I certainly agree with Miller’s broader message that sexual selection played a role in language evolution (in parallel with other selective forces of course) just perhaps not at the stage that he appears to identify – or maybe he should be more specific about how verbal competence was evaluated in the absence of language components such as syntax. In my opinion, his theory as it is at the moment is insightful insofar as it offers an engaging hypothesis as to why linguistic creativity may have been driven by sexual selection in the later stages of language evolution once the language components necessary for expressing it had evolved.

Hi Anne – I’ve Just read half Miller’s book – I’m a little confused as to what basis his claims are made? I.e how is his hypothesis formulated without direct evidence?

He also refers to language, and human creativity and intelligence – does he lump these all in together – i thought intelligence would be umbrella term for other unique human capabilities (and that this would include creatvity, music, sport, lang etc…) ?