![]() When examining the dispersal of Pleistocene hominins, one of the more fascinating debates concern the patterns of biological and technological evolution in East Asia and other regions of the Old World. One suggestion emerging from palaeoanthropological research places a demarcation between these two regions in the form of a geographical division known as the Movius Line. Specifically, the suggestions that initially led to the Movius Line were based on observations of differing technological patterns, namely: the lack of Acheulean handaxes and the Levallois core traditions in East Asia.

When examining the dispersal of Pleistocene hominins, one of the more fascinating debates concern the patterns of biological and technological evolution in East Asia and other regions of the Old World. One suggestion emerging from palaeoanthropological research places a demarcation between these two regions in the form of a geographical division known as the Movius Line. Specifically, the suggestions that initially led to the Movius Line were based on observations of differing technological patterns, namely: the lack of Acheulean handaxes and the Levallois core traditions in East Asia.

Since Hallam L. Movius’ initial proposal, the recent discovery of handaxes within East Asia have led to suggestions that the Movius Line is in fact obsolete. Suggesting this may not in fact be the case is a recent paper by Stephen Lycett & Christopher Norton, which highlights three central points coming from a growing body of research: 1) “several morphometric analyses have identified statistically significant differences between the attributes of specific biface assemblages from east and west of the Movius Line”; 2) “The number of sites from which handaxes have been recovered in East Asia tend to be geographically sparse compared with many regions west of the Movius Line”; 3) “‘handaxe’ specimens tend only to comprise a small percentage of the total number of artefacts recovered, a situation that contrasts with many classic Acheulean sites in western portions of the Old World, where bifacial handaxes may dominate assemblages in large numbers”.

In light of these developments, the current paper combines cultural transmission theory and demography to produce a “generalised model for Palaeolithic technological evolution during the Pleistocene”. As it is generally assumed, cultural transmission underlies technological traditions, which may be taken as “a particular behaviour (e.g., tool manufacture and use) that is repeated over generations, and is learned and passed on between individuals via a process of social interaction”. Furthermore, we now also know such forms of transmission can be modelled in an analogous manner to that of genetic transmission. In fact, the parallels between genetic and cultural transmission extend to the point where “factors known to structure patterns of genetic variation and transmission (e.g., drift, selection, dispersal and demography) must also be taken into account when examining patterns of cultural variation across space and time”.

Like in population genetics, Lycett & Norten refer to effective population size (Ne), except instead of meaning the number of individuals actively involved in passing on genetic material, they use the term to mean “the number of skilled practitioners of a given craft tradition involved in passing on those skills to subsequent generations via social transmission”. As such, small effective populations rely more on stochastic factors, such as drift, in shaping which cultural variants will be passed on to future generations. By contrast, large populations are less likely to be impacted upon by stochastic sampling effects – allowing for a greater number of innovations to diffuse throughout the population. This is supported via mathematical modelling, which shows:

[…] that a decrease in effective population size (Ne) may lead to a loss of pre-existing socially transmitted cultural elements… [therefore] the greater the number of models, the more choice is available for selecting the best (i.e. most skilled) models from which to copy. That is, in larger populations, cumulative cultural learning is possible because the effect of having a larger number of models from which to pick the most skilled, exceeds the losses resulting from imperfect copying of that skill. Hence, the chance of copying the most skilled elements of a given practice correlates directly with the number of models from which to copy.

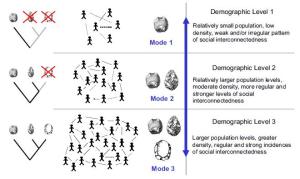

An example of these demographic conditions in action comes from the Tasmanian Islanders. When Tasmania became isolated from Australia approximately 10-12 thousand years ago, the newly established islanders appear to have lost and/or never developed the ability to manufacture a range of technologies, including: fishing spears, cold-weather clothing and boomerangs. Described as a ‘cultural founder effect’, Lycett & Norton use these observations to implement the following three conditions in constructing their model: population size, density and social interconnectedness:

Social interconnectedness reflects the likelihood of encountering a given craft skill and the regularity of such encounters. Social interconnectedness is thus somewhat proportional to the parameters of effective population size (i.e. number of skilled craft practitioners) and population density (i.e. probability of encounter due to degree of aggregation).

By varying these population conditions, Lycett and Norton use their model to show how different stages of lithic technologies may be sustained (see figure below, taken from Lycett & Norton(2010)). Crucially, demographic levels may decrease and lead to a situation where sustaining already-created technological innovations may not be tenable for the long-term. In providing a null model, they remain neutral as to the effects of cognitive and biomechanical evolution on the emergence and disappearance of technological patterns. In fact, the demographic processes described (larger populations and greater density) mirror those conditions under which human biological evolution may have accelerated. Meaning, human population structures are advantageous for the spread of novel technologies, cultural variants and adaptive genes. This may have implications for why we are seeing growing evidence of gene-culture coevolution in modern human populations.

Although it’s prohibitively difficult to estimate the demographic parameters of ancient hominin populations, it is fairly certain that demographic levels will have been relatively higher within Africa than in other parts of the world during the Early to Middle Pleistocene. When coupled with evidence showing the earliest First Appearance Dates (FADs) for Mode 1, Mode 2 and Mode 3 technologies in Africa, the demographic model presented is certainly congruent with the assertion that there is a definitive link between the spread of technological innovations and sustained population growth. Thus, if hominin populations were temporally and spatially discontinuous, then they simply lacked the necessary population conditions to maintain a certain degree of technological sophistication. By extension, explaining the relative absence of bifacial implements in East Asia is perhaps a demographic problem.

As mentioned earlier, we do see some evidence for Acheulean technology in East Asia. But this is not a refutation of the model. Rather, the discovery of these technologies perfectly fits within the model, especially as it is not at any significant level when compared to those found west of the Movius Line. That is, even if Acheulean technologies were imported to East Asia, the demographic conditions would be unfavourable in maintaining them. In this case, we would expect to see Acheulean technology at relatively low densities in East Asia. As the authors note:

One further observation that is not often noted is that the artefact density of most of the Early Palaeolithic sites in East Asia is also usually very low. For instance, in Fangniushan and Chenshan, two Middle Pleistocene open-air sites in central-east China, the artefact densities are less than one per m3

Of course, artefact density may be influenced by a whole host of factors. Raw material availability is one example. More broadly, the markedly different technological patterns observed may not be causally related to demography at all. We could find evidence for sharp cognitive differences between hominin populations east and west of the Movius Line. However, the authors predict that these explanations will become increasingly problematic if “site densities and the chronological distribution of sites in East Asia […] continue to differ from those in the west”.

But this is what’s great about null models: they are testable. In this case, the model predicts that:

[…] evidence for demographic levels in East Asia will be found to be significantly different from those in many parts of western Eurasia and Africa during the Early and Middle Pleistocene. Here, we have hinted at some of the currently available evidence that suggests this may have been the case. What is now urgently needed are more sophisticated means than we have provided here of assessing Pleistocene demographic parameters in the key regions east and west of the Movius Line.

So it’s still very much an open question as to why we find differing technological patterns east and west of the Movius Line. But demography certainly seems like a good candidate.

Citation

Lycett, S., & Norton, C. (2010). A demographic model for Palaeolithic technological evolution: The case of East Asia and the Movius Line Quaternary International, 211 (1-2), 55-65 DOI: 10.1016/j.quaint.2008.12.001

The fact that one significant site that had mid-Pleistocene bifaces turned out to be a complete fake (in Japan) is interesting.