Over at ICCI are a couple of blog posts by Olivier Morin about project I’m involved in, the Color Game. The first post provides an introduction to the app and how it will contribute to research on language and communication. And, as I mentioned on Twitter, the second blog post highlights one of the Color Game’s distinct advantages over traditional experiments:

One really cool aspect about working on the Color Game is the diversity of participants. See more here: https://t.co/s5aENGCUJg

— James Winters (@replicatedtypo) May 30, 2018

An ambitious project

What I want to briefly mention is that the Color Game is an extremely ambitious project that marks the culmination of two years worth of work. A major challenge from a scientific perspective has been to design multiple projects that get the most out the potential data. Experiments are normally laser-focused on meticulously testing a narrow set of predictions. This is quite rightly viewed as a positive quality, and it is why well-designed experiments are far better suited for discerning mechanistic and causal explanations than other research methods. But I think the Color Game does make some headway in addressing long-standing constraints:

- Limitations in sample size and representation.

- Technical challenges of scaling up complex methods.

- Underlying motivation for participation.

Sample size and representation

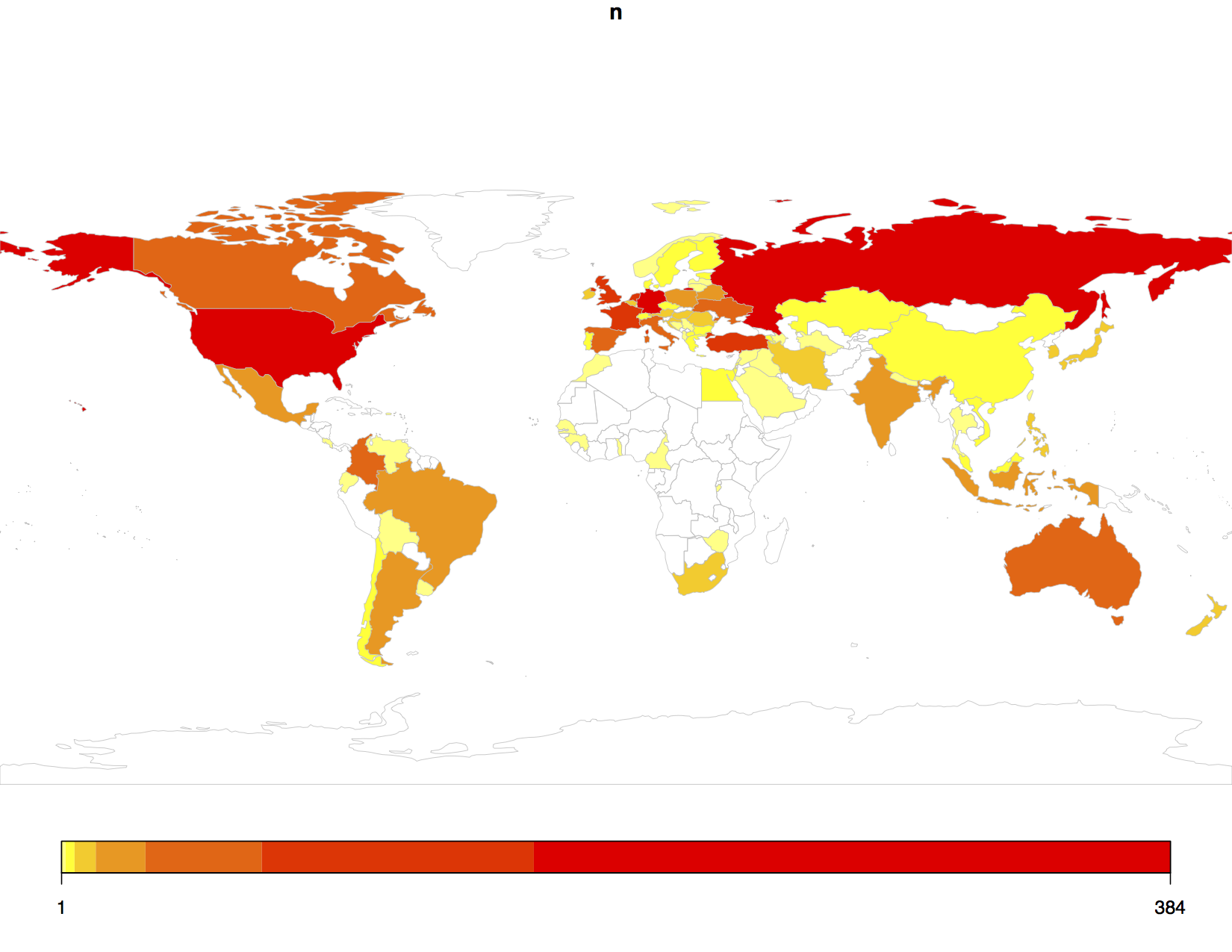

Discussions about the limitations of experiments in terms of sample size and the sample they are representing are abundant. Such issues are particularly prevalent in the ongoing replication and reproducibility crisis. Just looking at the first week of data for the Color Game and there are already over a 1000 players from a wide variety of countries:

By contrast, many psychological experiments will be lucky to get an n of 100, and this number is often determined on the basis of reaching sufficient statistical power for the analyses (cautionary note: having a large sample size can also be the source of big inferential errors). It is also the case that standard psychology populations are distinctly WEIRD. Apps can help connect researchers with populations normally inaccessible, especially given the proliferation of mobile phones.

Technical challenges

The Color Game’s larger and more diverse sample leads to my second point: that scaling up complex methods is both costly and technically challenging. Even though web experiments are booming, and this can mitigate the downside of having a small n, they are often extremely simple and restricted. Prioritising simplicity is fine if it is premised on scientific principles, but there is also the temptation to make design choices for reasons of expediency.

So, to give one example, if you want participants to complete your experiment, then making the experiment shorter (through restricting the number of trials and/or the time it takes to complete a trial) increases the probability of finishing. It can also lead to implementing methodological decisions to make the task technically easier. All else being equal, it is simpler to create a pseudo-communicative task (where the participant is told they are communicating with someone, even though they aren’t) than it is to create an actual communicative task. Same goes for using feedback over repair mechanisms.

All experiments are faced with these problems. But, anecdotally, it seems to be acutely problematic for web-based experiments. Just to be clear: I’m not making a judgement about whether or not a study suffered from making a particular methodological choice. The point is to simply say that these design choices should (where possible) first consider the scientific consequences above technical and practical expediency. My worry is that when scientific considerations are not prioritised, you lose too much in terms of generalisability to real world phenomena. And, even when this is not the case and the experiment is justifiably simple, I wouldn’t be surprised to find that this creates a bias in the types of web experiments performed. In short, there’s the possibility that web-based experiments systematically underutilise certain methodological designs, leading to a situation where web-experiments occupy and explore a much narrower region of the design space.

I hope that the Color Game makes some small steps towards avoiding this pitfall. For instance, we incorporated features not often found in other web-based communication game experiments, such as the ability to communicate synchronously or asynchronously and for participants to engage in simple repair mechanisms instead of receiving feedback. Players are also free to choose who they want to play with in the forum, giving a much more naturalistic flavour to the interaction dynamics. This allows for self-organisation and it’ll be interesting to see what role (if any) the emergent population structure plays in structuring the languages. App games, similar to 얀카지노, therefore, offer a promising avenue for retaining the technically complex features of traditional lab experiments whilst profiting from the larger sample sizes of web experiments.

Having a more complex set up also allowed us to pre-register six projects that aim to answer distinct questions about the emergence and evolution of communication systems. To achieve a similar goal with other methods is far more costly in terms of time and money. But there are downsides. One of which is that the changes and requirements imposed by a single project can impact the scope and design of all the other projects. Imagine you have a project which requires that the population size parameter is manipulated (FYI, this is not a Color Game project): every other project now needs to control for this fact be it through methodological choices (e.g., you only sample populations with x number of players) or in the statistical analyses.

In some sense, this reintroduces the complexity of the real-world back into the app, both in terms of its upsides and downsides. Suffice to say, we tried to minimise these conflicts as much as possible, but in some cases they were simply unavoidable. Also, even if there are cases where this introduces unforeseen consequences in the reliability of our results, we can always follow up on our findings with more traditional lab experiments and computer models.

Online slot games are known for their easy-to-understand mechanics, making them accessible for all types of players. For the best experience, it’s important to pick a slot gacor game, as these tend to offer better rewards. LIMO55 is a great platform to explore these games, offering a range of options for both novice and experienced players. With exciting visuals and engaging gameplay, it’s easy to get hooked on these games.

Underlying motivation

Assuming I haven’t managed to annoy anyone who isn’t using app-based experiments, I’ve saved my most controversial point for last. It’s a hard sell, and I’m not even sure I fully buy it, but I think the underlying motivation for playing apps is very different from participating in a standard experiment. At the task level, the Color Game is not too dissimilar from other experiments, as you receive motivation to continue playing via points and to get points in the first place you need to be successful in communication. Where it differs is in terms of why people participate in the first place. In short, the Color Game is different because people principally play it for entertainment (or, at least, that’s what I keep telling myself). Although lab-based experiments are often fun, this normally stands as an ancillary concern that’s not considered crucial to the scientific merits of a study. It’s encouraging to see how app developers are creating engaging platforms that not only entertain but also advance scientific research in meaningful ways.

Undergraduate experiments are (in)famously built on rewards of cookies and cohort obligations, and it is fair to say that most lab experiments incentivise participation via monetary remuneration (although this might not be the only reason why someone participates). Yet, humans engage in all sorts of behaviours for endogenous rewards, and app games are really nice examples of such behaviour. People are free to download the game (or not), they can play as little or as much as they please, and as I’ve already mentioned there is freedom in their choice of interaction partners. Similarly, in the real-world, people have flexibility in when and why they engage in communicative behaviour, with monetary gain being just a small subset (e.g., a large part of why you don’t have to go far to find a motivational speaker is because they earn money for public lectures and other speaking events).

If you’re interested, and want to see what all the fuss is about, feel free to download the app (available on Android and iOS):

Do have an idea why the “proliferation of mobile phones” – in particular in Africa, as the linked article states – doesn’t show in your user distribution (so far you seem to have the “usual suspects”, i.e. Egypt and South Africa, for any web service)? My first guess would be that “mobile phone” isn’t “smartphone”. But it could also be the myriad of (mostly outdated) smartphone operating systems which prevents uptake?

Good question. My guess would probably align with yours: that many of the smartphones are outdated (in terms of OS) and this inhibits uptake. But it could also be the case that we didn’t do a very good job at promoting the game in many African countries.