We all take comfort in our ability to project into the future. Be it through arbitrary patterns in Spring Pouchong tea leaves, or making statistical inferences about the likelihood that it will rain tomorrow, our accumulation of knowledge about the future is based on continued attempts of attaining certainty: that is, we wish to know what tomorrow will bring. Yet the difference between benignly staring at tea leaves and using computer models to predict tomorrow’s weather is fairly apparent: the former relies on a completely spurious relationship between tea leaves and events in the future, whereas the latter utilises our knowledge of weather patterns and then applies this to abstract from currently available data into the future. Put simply: if there are dense grey clouds in the sky, then it is likely we’ll get rain. Conversely, if tea-leaves arrange themselves into the shape of a middle finger, it doesn’t mean you are going to be continually dicked over for the rest of your life. Although, as I’ll attempt to make clear below, these are differences in degrees, rather than absolutes.

So, how are we going to get from tea-leaves to Lingua Francas? Well, the other evening I found myself watching Dr Nicholas Ostler give a talk on his new book, The Last Lingua Franca: English until the Return to Babel. For those of you who aren’t familiar with Ostler, he’s a relatively well-known linguist, having written several successful books popularising socio-historical linguistics, and first came to my attention through Razib Kahn’s detailed review of Empires of the Word. Indeed, on the basis of Razib’s post, I was not surprised by the depth of knowledge expounded during the talk. On this note alone I’m probably going to buy the book, as the work certainly filters into my own interests of historical contact between languages and the subsequent consequences. However, as you can probably infer from the previous paragraph, there were some elements I was slightly-less impressed with — and it is here where we get into the murky realms between tea-leaves and knowledge-based inferences. But first, here is a quick summary of what I took away from the talk:

- By looking at historical instances of lingua francas we can derive broad-stroke themes about their rise and fall through migration, conquest, trade and conversion. For instance, during the 16th Century the languages, Nahuatl and Quechua, respectively the lingua francas of the Aztec and Inca empires, were systematically displaced by Spanish — the language of their new conquerors. Ironically, the same processes that give rise to lingua francas are also responsible for their fall: that is, it is costly to maintain linguistic homogeneity across culturally heterogenous populations. (N.B. It’d be interesting to see if this is fragility is especially prevalent when the respective sub-communities that make up the dispersion of a lingua franca retain their original languages.)

- We can use these historical tales of lingua francas to inform our future understanding of current lingua francas, such as English, and make predictions about their demise.

- Lastly, Ostler makes the prediction that English is the last lingua franca; due to translation technology, hopefully not based on Google’s attempt, there will be an explosion in the diversity of languages. For some examples of this linguistic utopia, see Jim Hurford’s fascinating short story, Desperanto, or, for those of a more visual inclination, check out Japan’s World Cup bid:

On his first point I don’t have any pressing arguments. On the second and third points I’m slightly more sceptical. I think a lot of work into historical change, such as cliodynamics, is brilliant stuff — and I’m hoping to eventually use this to inform my own work. However, using history to make long-term projections is, quite frankly, ridiculous when dealing with multifaceted problems and complex payoffs. And, in case you hadn’t guessed, the rise and fall of lingua francas is not simple. Ostler does rely on current data to inform his predictions, and for this I applaud him, but it was exactly because of his approach that I kept thinking of Malthus’ own predictions about population collapse and how they turned out to be wrong. During the Q&A, Ostler dismissed the comparisons, claiming Malthus’ work was a theoretical construct, which, even if it was the case, still ignores the unpredictability of rapidly changing technological and cultural systems, and how they will filter through in determining future states. As it turns out, Malthus’ failure was not a lack of data, but rather a lack of precognitive capacities (or some magical tea leaves):

Malthus did not rely just on mathematics to school his intuition. Lindert (1985) examined the data that Malthus has available to him in his lifetime. Within the limits of his day, Malthus’s knowledge of demographic patterns in different countries was extensive. Lindert argues that not until after Malthus’s death did the English economy begin to produce sustained per capita growth. On the other hand, the time in which Malthus lived was the beginning of the Industrial Revolution. Most likely, the rate of technological improvement that Malthus inferred from the data available to him was indeed rapid compared with most periods in human history (Richerson, Boyd & Bettinger, 2009).

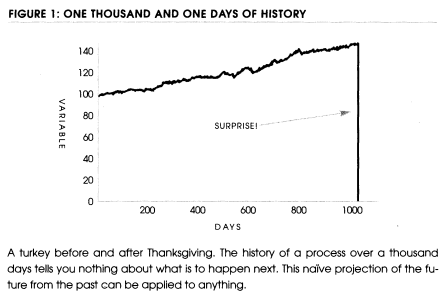

Obviously, we can only draw so many parallels between Ostler and Malthus, but even with a greater access to statistical tools, methodologies and 200-or-so-years worth of scientific and cultural change, Ostler is still constrained by the realm of uncertainty. That is, if you’ve got a good model of history, it doesn’t mean you’ve got a good model of the future. To demonstrate this, I’ll borrow Nassim Nicholas Taleb’s Turkey Metaphor: A Turkey is fed for a 1000 days—every days confirms to its statistical department that the human race cares about its welfare “with increased statistical significance”. On the 1001st day, the turkey has a surprise…

I’ll quote Razib Khan’s conclusion from earlier this year (see here):

But the past 200 years are qualitatively different from what has come before, and there is already a revolution in communication technology. It may be that in the future languages do not crystallize as a function of geography, but perhaps more as a function of class and occupation. It does seem historically that trade lingua francas have been ephemeral in impact, and English, the language of McWorld, is the language of capital. But the modern world is much more dependent on flows of capital and commerce than the pre-modern world, the Sogdians and Portuguese were primarily vectors for high value luxury goods. Pre-modern capitalism had the air of a parlor game between the high and mighty, and was quite often in bad odor among rentier elites themselves. It is with reason that I observed above that the pace of cultural change in the past was less than what it is today. Positive feedback loops may be much more powerful than they once were, so that a “Globish” derived from English may quickly sweep away all comers, before it diversifies again.

In some senses, you can forgive Ostler’s foray into technological determinism, as his pessimistic outlook on the future of English stands in stark contrast to the rosy optimism of David Crystal and company. There are good reasons, however, not to trust Ostler’s predictions. Changes in language, like changes in the economy, are subject to fourth-quadrant, or Black Swan, style phenomena, which provides areas of unpredictability that cannot be accounted for, regardless of the amount of prior data you collect. Ostler might very well have his finger on the pulse of technological advances affording an increase in diversity. Equally, the development of technology might result in language convergence; it all depends on the constraints imposed by the translation software, and the socio-cultural institutions that utilise them. Even more likely is that we simply don’t know the outcomes. Taking a neutral stance on the future of English might be boring, but it’s probably the best perspective given the language’s unique historical development and the various contingencies vital for its future states.

In summary, Ostler’s talk was a fascinating account of Lingua Francas, yet it left me wondering whether his predictions are merely a case of epistemic arrogance, which, when appearing in book form, costs a great deal more than tea leaves.

Note: This article was pretty much completed earlier on in the year, and was based on a talk given by Dr Ostler on at Cardiff University: The life and death of lingua-francas (Is English just one more?). I forgot to publish it, and the talk was in February, so it’ll probably go down in my own personal achievements of prolonging a blog post. P.s. I still haven’t bought the book.

References

Taleb, N. (2007). Black Swans and the Domains of Statistics The American Statistician, 61 (3), 198-200 DOI: 10.1198/000313007X219996

Is this talk still online? (I was reading bits of Taleb’s new book at http://www.salon.com/2012/12/01/nassim_nicholas_taleb_the_future_will_not_be_cool/ and later found your post. A less-boring stance on English’s future that seems as simple as the boring neutral one seems to be where of course in the long run English will be displaced as a lingua franca, whether it’s machine translation or not.)

Thanks for the comment. Your point that English is likely to be displaced by machine translation is basically what Ostler is saying. I’m not saying that this is wrong, but there are a few, simple reasons why the impending decline of English might never happen. First, English appears to be growing in usage, not shrinking (see here). Also, interestingly enough, if you look at the usage of content languages for websites, then English appears to have increased here as well (see 2013 and compare it with 2010). N.B. I wouldn’t consider either of these as strong sources of evidence and I might try and dig out something a bit more empirically valid.

Lastly, we can actually turn to a quote from Taleb himself, on the difference between perishable and non-perishable domains: “For the perishable, every additional day in its life translates into a shorter additional life expectancy. For the nonperishable like technology, every additional day may imply a longer life expectancy.” (The Surprising Truth: Technology Is Ageing in Reverse). In short, the longer a language lives, the longer it is expected to live. Whether this translates as continued dominance as a lingua franca is as good a guess as any.

On the talk itself: as far as I’m aware there isn’t a recording of it. But I did find a link to another talk on the same topic (MT as the new Lingua Franca).