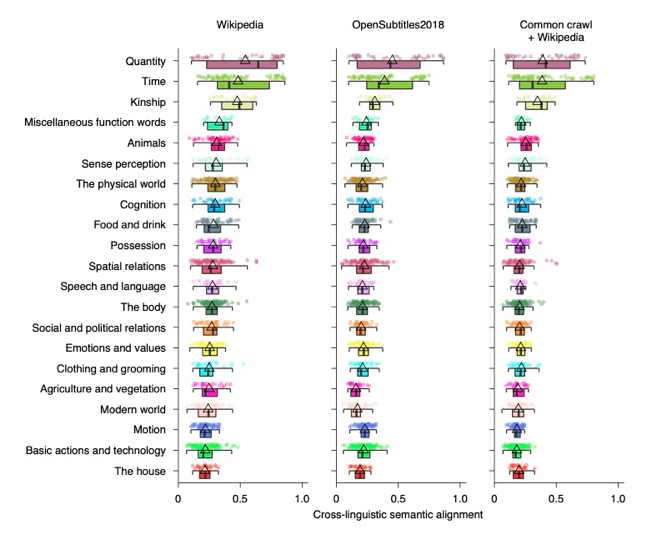

Last week, Bill Thompson, Gary Lupyan and I published a paper using word embeddings to look at semantic similarity between languages (copy of paper here). We showed that some semantic domains are more closely aligned (i.e., are more translatable) than other domains.

But what would linguists actually predict? Before the paper was released, Bill and Gary ran a survey of linguists, asking them to predict our results. Gary tweeted the results, and I’ve collected them here (text and graphs by Gary).

Survey results

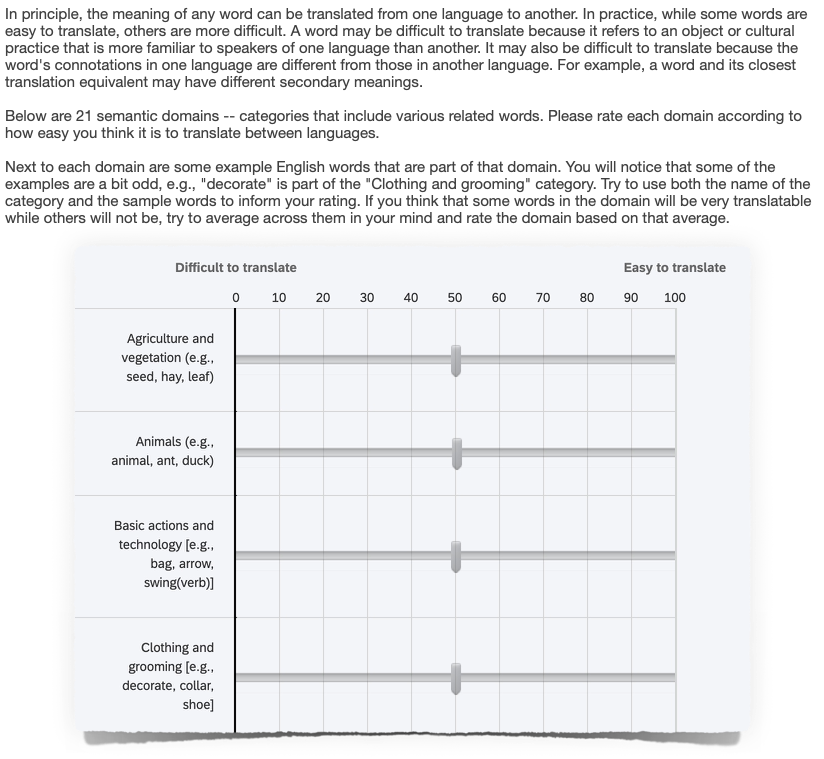

Prior to the paper being published, we conducted a survey asking people to indicate what they thought were the most and least translatable domains:

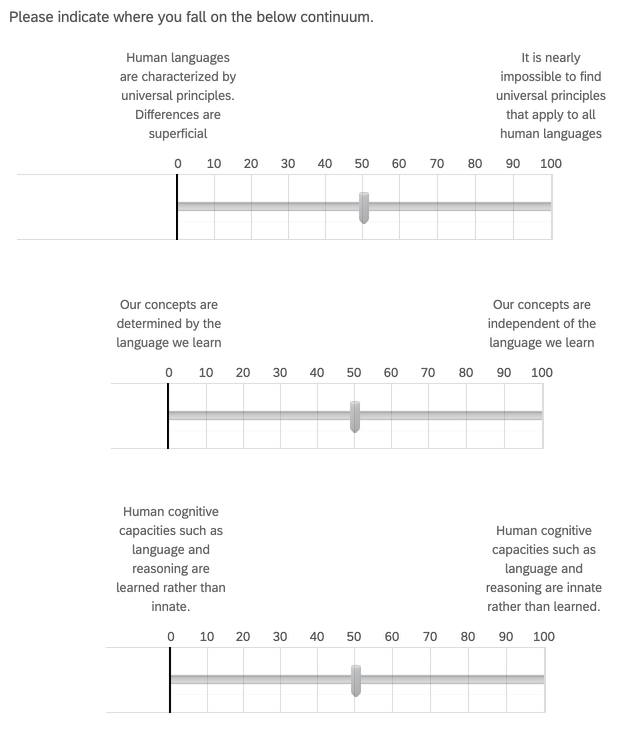

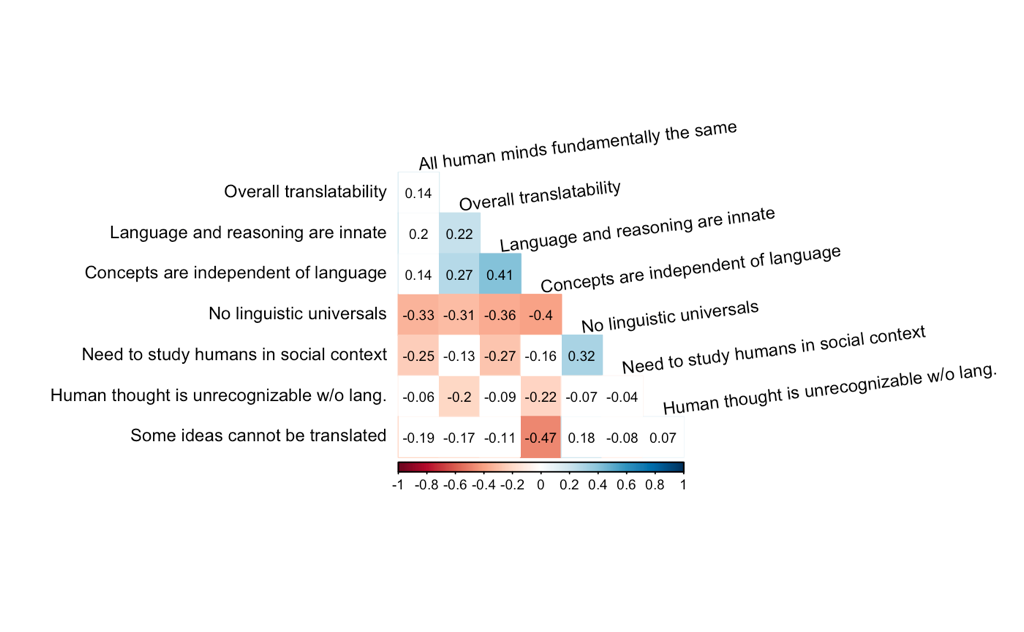

Our primary goal was to see whether people who subscribed to more universalists vs. relativist views on language ranked the domains differently. We measured universalist/relativist leanings by having people respond to questions like these:

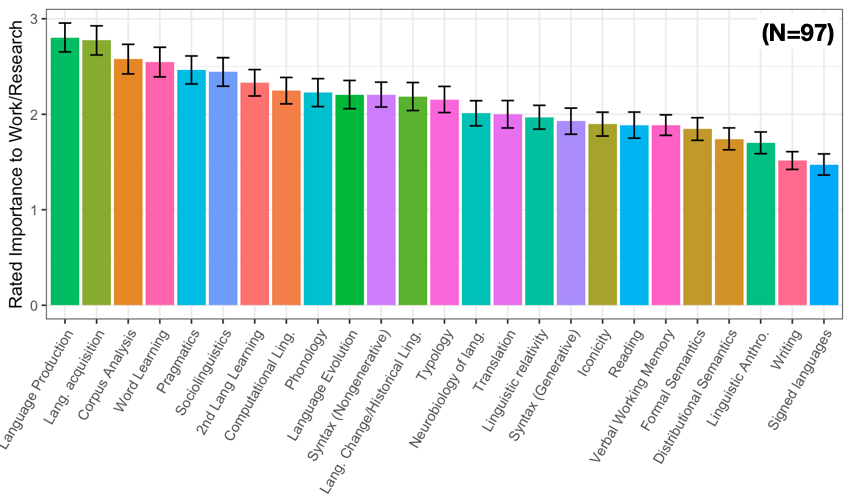

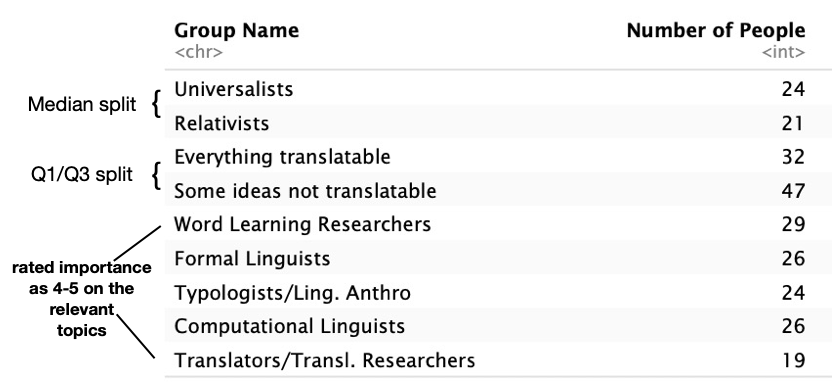

And we also asked what kinds of things people research/work on. We had 97 complete responses. (Thank you!!) spanning various language research disciplines.

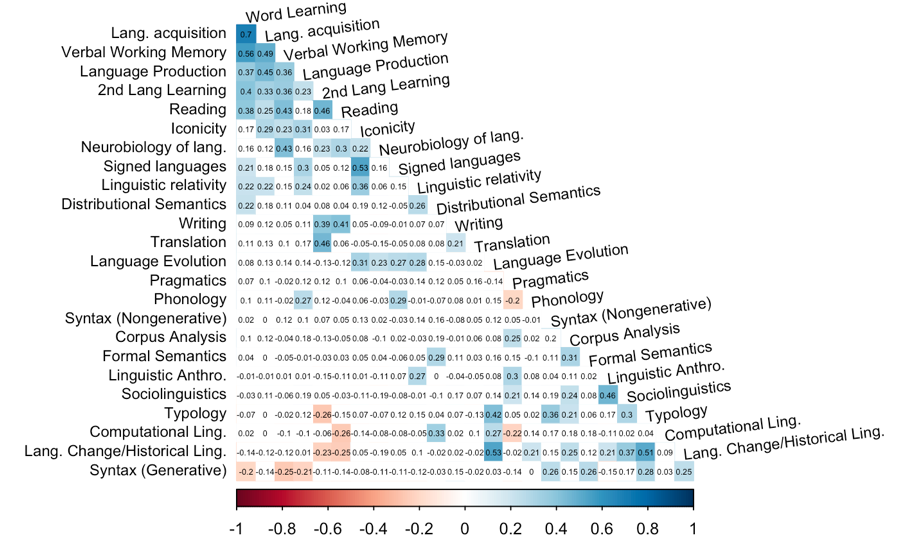

Here are the correlations between how respondents rated the importance of methods and the importance of topics (using 1st principal component to cluster). There’s not much that’s surprising here. (Colored squares are p<.05).

We can also see: People who think concepts depend on language more likely to think that some ideas cannot be translated. Those who think social context is important tend to deny linguistic universals. Those who think language is innate think concepts are independent of language.

We next created a few discrete groups. “Universalists” are people who think that there are ling universals, that our concepts are independent of natural language, and language is largely innate. “Relativists” are those who scored on the other side of the median on those questions.

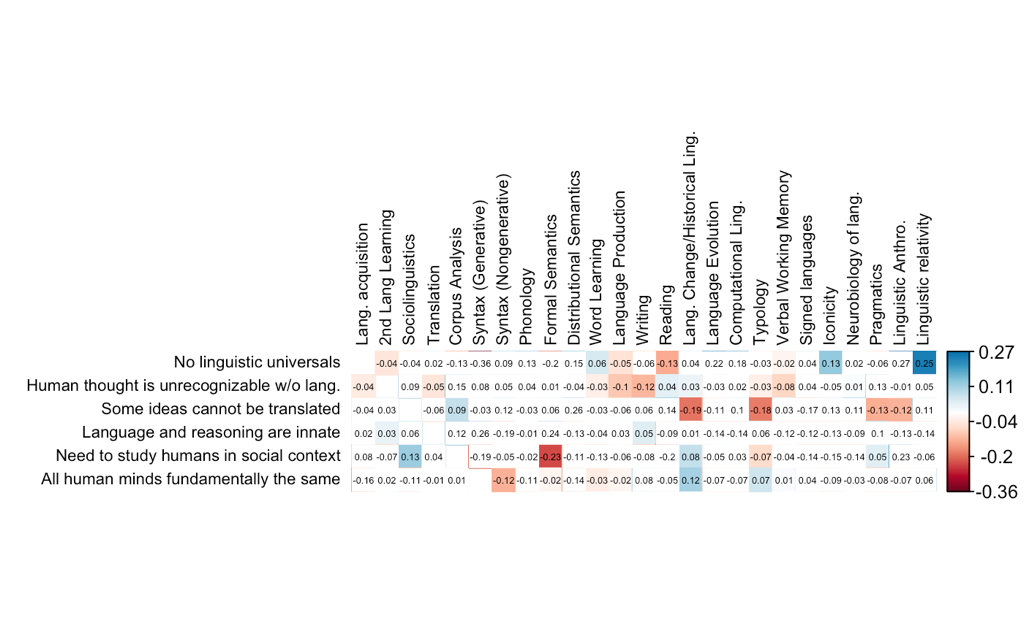

Where do researchers who study different things fall on their beliefs about innateness, universality, etc.? Formal semanticists think social context doesn’t matter much. Researchers studying linguistic relativity are more likely to think there aren’t linguistic universals. Again, not surprising. But nice to see numbers.

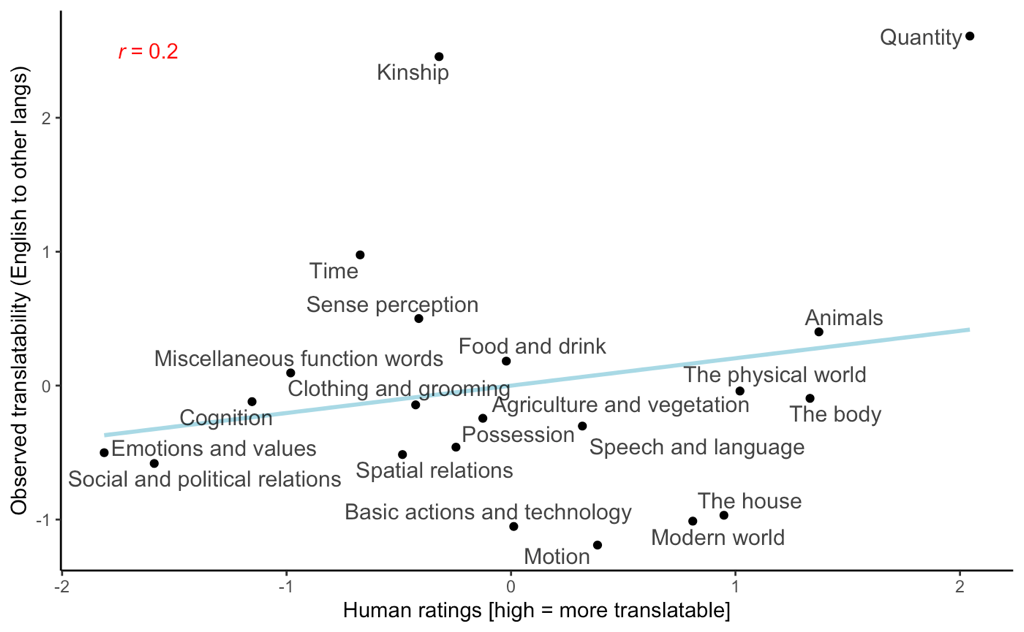

Now on to translatability ratings of domain. Overall, the correlation is rather low and primarily driven by Quantity which is ranked as the most translatable both by our respondents and in our data.

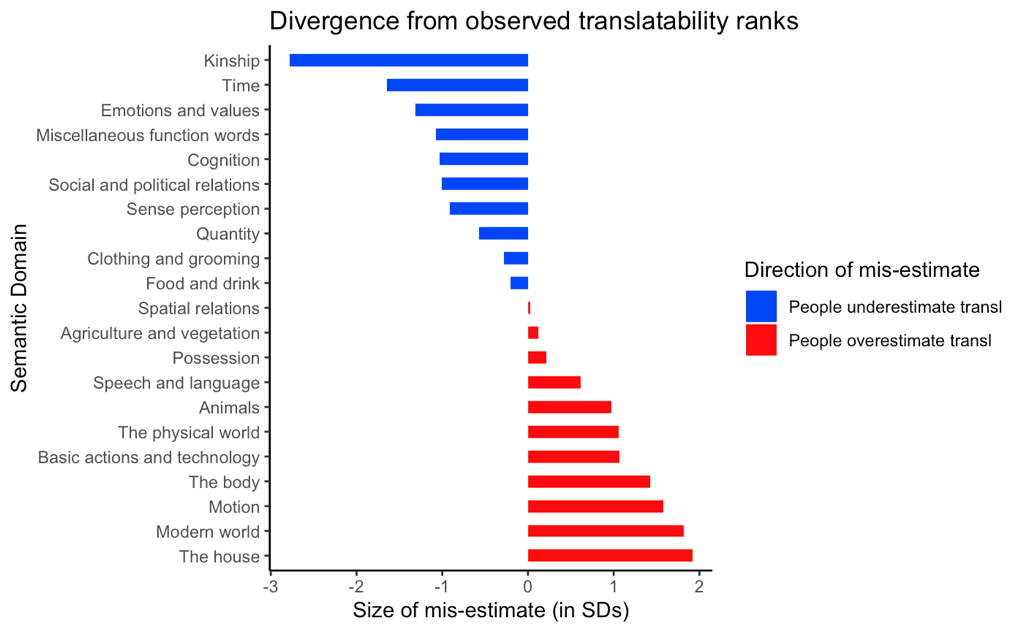

The graph below shows the size and direction of people’s mis-estimates. Kinship terms are, in reality, quite translatable, but people think they are not. Terms relating to the house (e.g., bed, ladder, chair) are rated by people as highly translatable, but our data indicate this is not so.

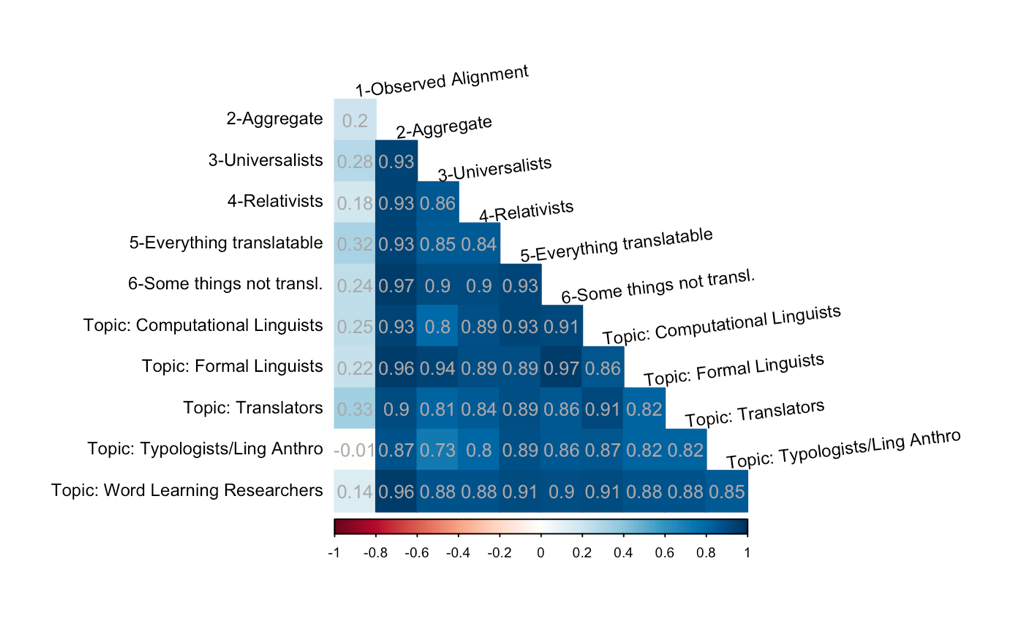

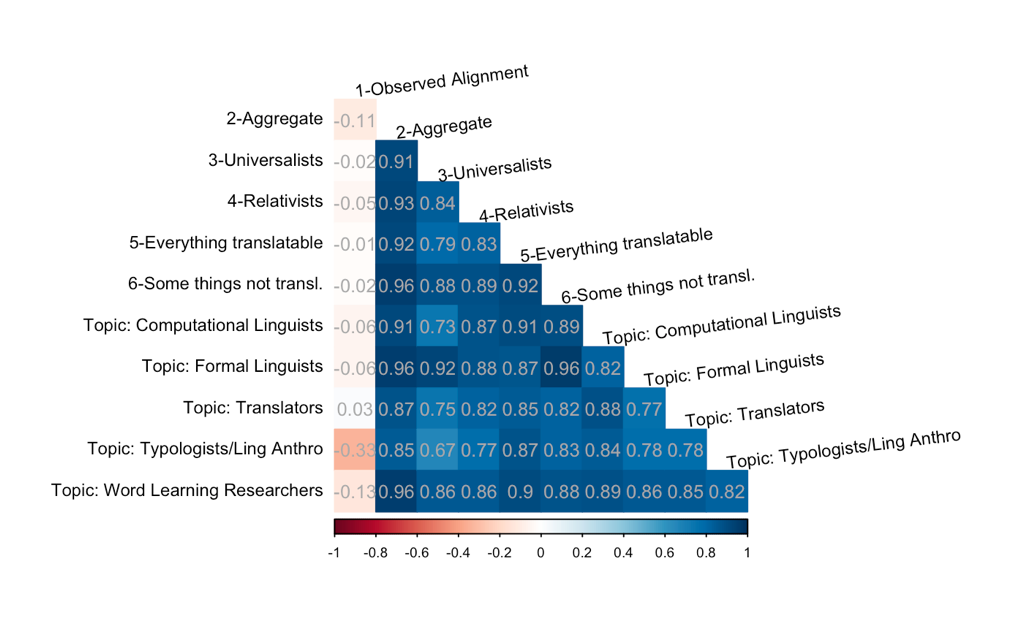

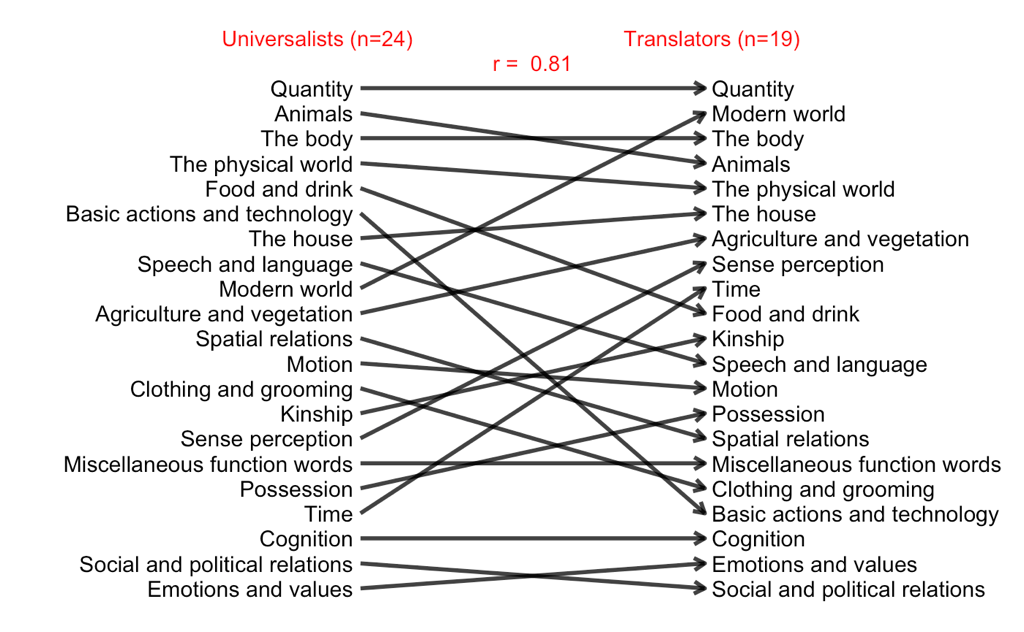

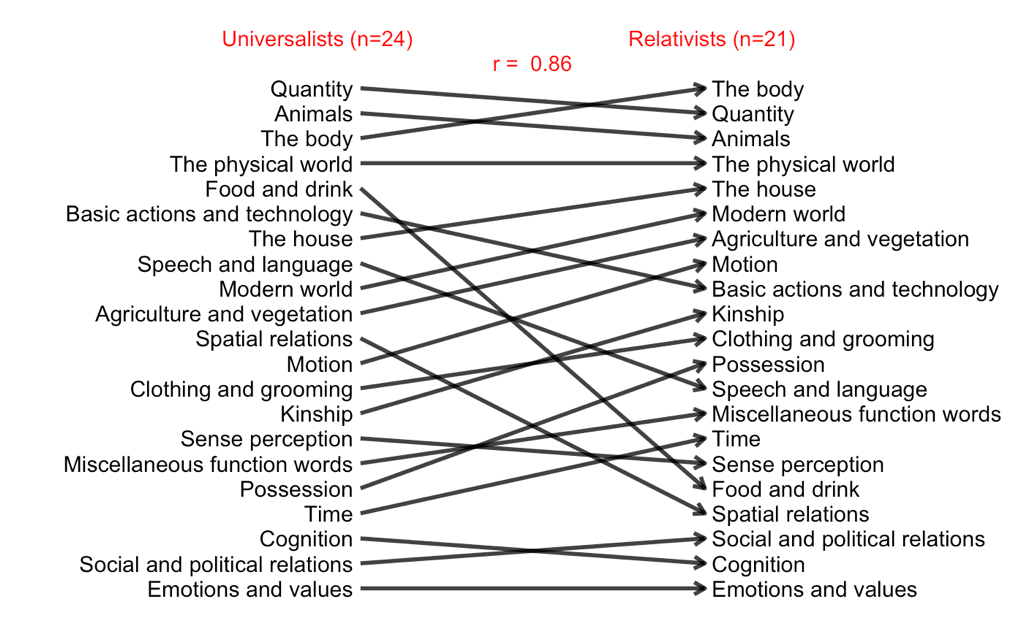

The graph below shows the correlations between participant groups and observed data. Some groups came closer to the observed ranking than others. Researchers studying/doing translation had the numerically higher correlation to the observed data. Notably people respond similarly regardless of their theoretical stance.

If we exclude the quantity domain, people’s ratings remain similar to one another, but correlations with the observed data drop to 0 and in some cases turn negative.

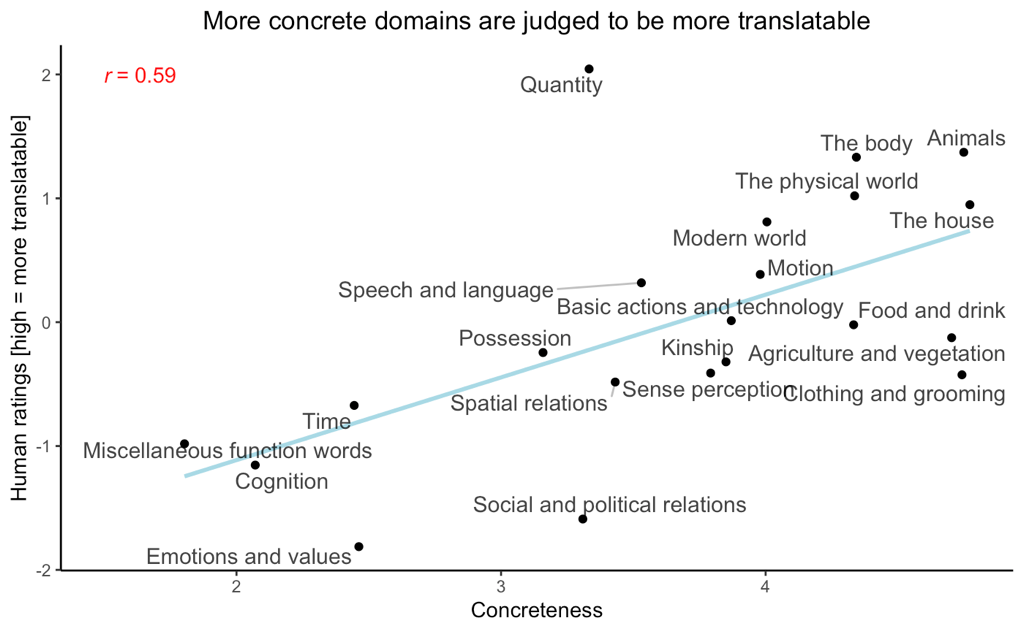

Below is a graph showing the respondent’s ratings compared to the concreteness of the words in the domain. As some may suspect, the domains people think of as highly translatable, tend to be the more concrete ones: animals, household objects, the physical world. Universalists especially think that these domains are highly translatable.

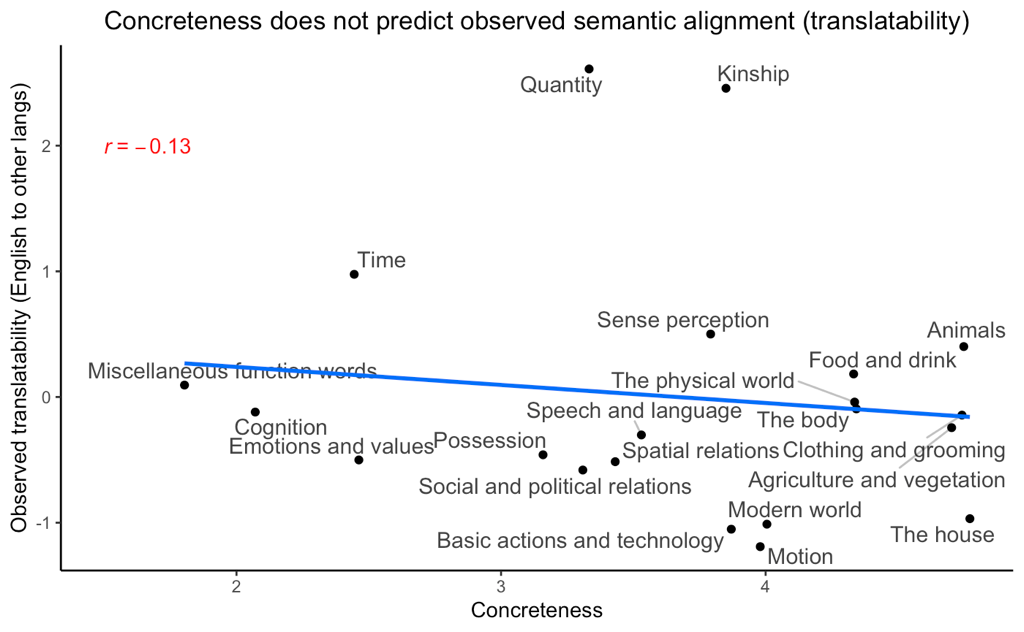

But translatability as estimated by our semantic alignment measure turns out to be unrelated to concreteness, helping to explain why people’s estimates deviate so systematically.

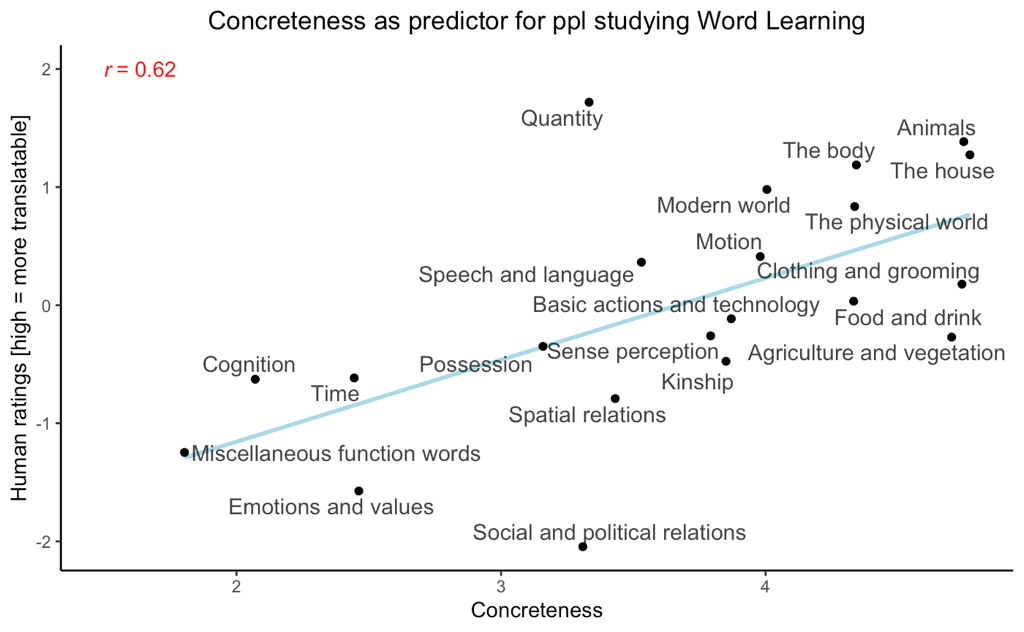

Interestingly, not all respondents were equally driven by concreteness. E.g., people studying word learning tended to rely quite heavily on concreteness when estimating translatability.

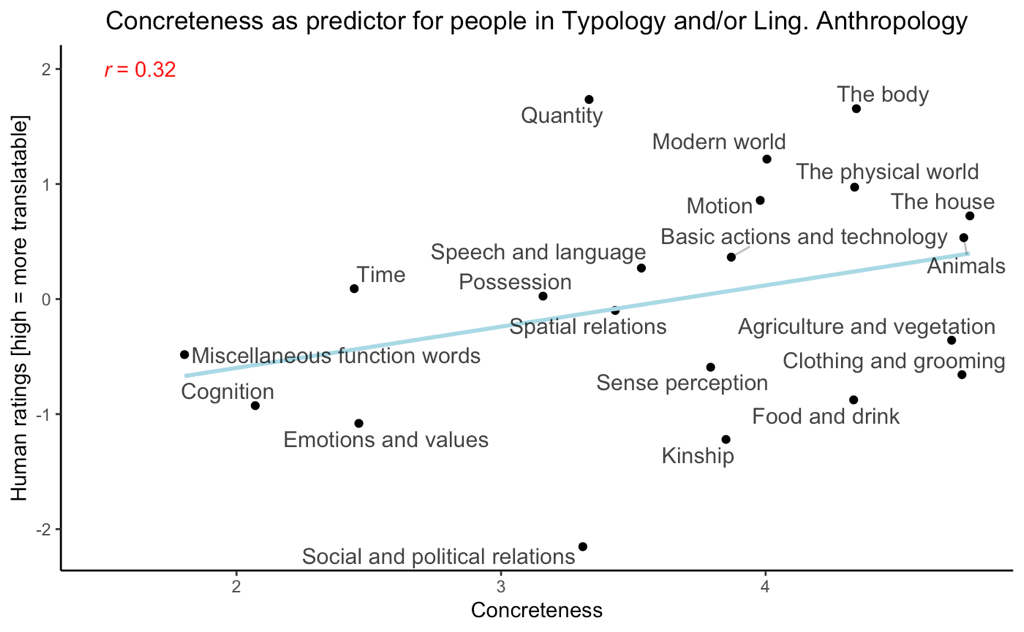

Responses of people in typology and/or linguistic anthropology were much less driven by concreteness.

Compared to “universalists”, who rate seemingly objective domains (animals, food/drink, basic actions) as very translatable, people with more experience in translation rate these domains much lower.

“Relativists” also tend to recognize that the language used to describe food and drink can vary substantially.

What did we Learn?

With the exception of the domain of Quantity (judged by most to be very translatable), people’s ratings of which domains are translatable deviated substantially from what we obtained using the semantic alignment method described in our paper. But for the most part, people deviated from the observed data in quite similar ways with many being driven by concreteness: People think concrete words are easy to translate and more abstract words are harder. Our data suggests that this intuition may not be correct. Many seemingly concrete categories are represented quite differently in different languages and may thus be hard to translate. More relational/abstract domains (e.g., number, kinship, time) may be structured very similarly by different langs.

The analysis script and (anonymised) data is available on request from Gary Lupyan.