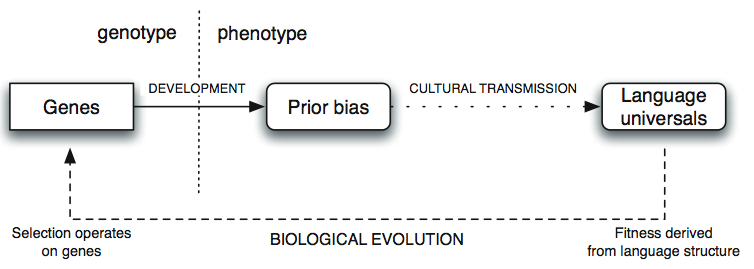

A cultural evolution approach to language suggests that genes encode weak prior biases that can be amplified through cultural transmission to produce strong language universals. Below is a diagram from Kirby, Dowman & Griffiths (2007).

Note the long-term feedback between language universals and genes. However, recent research is pointing towards a more complicated picture. Studies like Lupyan and Dale (2010) and Wray & Grace (2007), together with many issues discussed on this blog, show that there are links between the structure of a language and the structure of the society in which it is spoken. That is, social structures affect the dynamics of cultural transmission, which in turn affects the emergence of language universals. Since social dynamics can change quicker than genes, this allows a short-term feedback between social structure and language universals. Indeed, Gareth Roberts has shown that language structure and social structure can co-evolve rapidly (Roberts, 2010).

Similarly, studies of bilingualism are also pointing towards a short-term link. Children brought up in bilingual environments develop theory of mind earlier, metalinguistic awareness earlier, better executive control and exhibit differences in their approaches to learning (e.g. mutual exclusivity). This suggests that linguistic prior biases can be affected in the short-term by the amount of variation in the input. Furthermore, linguistic variation is often supported by social structures (e.g. two communities that trade).

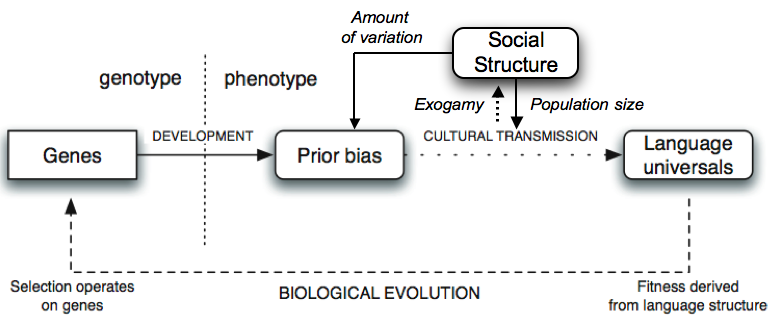

Below is an adaptation of the diagram above which includes social structure and some examples of process that affect cultural transmission and prior biases:

I’m not entirely happy with this adaptation – a potentially misleading aspect is that it blurs the distinction between the community and the individual – however, it illustrates my point – that social structure should be an integral part of a cultural evolution view of language.

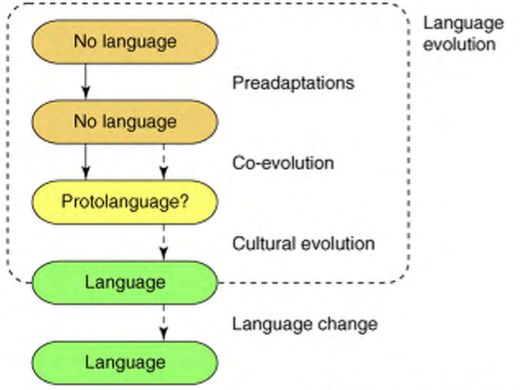

Although we can see that these short-term processes happening in modern times, were they also active at earlier stages of language evolution? Scott-Phillips and Kirby (2010) make a distinction between language evolution and language change (see diagram below). Would social structures have affected language structure at the protolanguage stage? Population size has already been invoked as a factor in the preadaptations for and co-evolution of language (Dunbar, 1998).

A long-running debate about protolangugae is the analytic versus the syntactic route to grammar. Very briefly, the analytic hypothesis suggests that utterances started out long and holistic, but random correlations between strings and meanings were analysed by language learners until compositional patterns emerged. The synthetic hypothesis suggests that utterances started out small and specific and were brought together to form more complex meanings. In other words, did language make up or break up?

The two hypotheses are, of course, not mutually exclusive. One possibility is that they are different extremes of the same process. We could view the analytic/synthetic processes as being related to inhibition and integration. When analysing utterances, inhibition is needed to focus on a particular part of the utterance/meaning and block out the rest. When synthesising utterances, sounds and meanings need to be integrated. Bilinguals appear to be better at inhibition tasks (e.g. task switching), but worse at integration (e.g. word retrieval). This has prompted Sorace (2011) to ask whether these two preferences are extremes of the same executive control mechanism that have been tuned to different tasks. Bilinguals need better inhibition to deal with codeswitching and suppressing words and structures in one language while speaking another. Monolinguals, on the other hand, can afford to divert more resources towards integration.

Therefore, analysis is more likely to be done by bilinguals and synthesis is more likely to be done by monolinguals. If this is possible, then the debate over whether proto-communities were monolingual or bilingual becomes very relevant. However, rather than arguing that one or the other was most prevalent (see here and here), it’s possible that both processes were active over successive generations as the community structure changed.

This hypothesis will require supporting evidence from many areas, and is just one of a number of new developments in the field which are encouraging interdisciplinary approaches.

Kirby, S., Dowman, M., & Griffiths, T. (2007). Innateness and culture in the evolution of language Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (12), 5241-5245 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0608222104

Scott-Phillips, T., & Kirby, S. (2010). Language evolution in the laboratory Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 14 (9), 411-417 DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2010.06.006

Sorace, Antonella (2011). Pinning down the concept of “interface” in bilingualism Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism, 1 (33)

One particularly notable example of cultural impact on language evolution that is visible if you browse the various maps you can make at WALS is in Mesoamerica where an independent New World Neolithic culture developed. The areas where that pre-Columbian agricultural system developed are different not just in areas you would expect (e.g. they have base twenty numbers absent in all other parts of the Americas and Asia), but lots of other ways (phonetics and grammatical structure, e.g.) that one wouldn’t naturally expect to logically flow from technological change.

In general, the agricultural areas had more complex language structure and it is a fair inference that this may have been facilited by a more complex social structure, and excess resources made available by agriculture generally, as well as novel and more complex things to talk about.

That’s an interesting idea, and me and James were just discussing the impact of farming on language, and how this interacts with the work on collectivism and individualism and migration. However, I’m not sure that agricultural communities would have initially had more resources than hunter-gatherer tribes (James was saying something about this), nor necessarily had more complex things to talk about. Perhaps there would be more of a need for cultural grooming, or hierarchies would be more stable? I don’t know much about the history of South America, although there has been some work done on cultural transmission and farming by Lee & Hasagawa (2011), blogged here.

Croft has a very good paper looking at the types of social structure and language change: Social evolution and language change. His main point is that different society types encourage certain types of language change, with some forms of language change being a product of very recent factors in human history. For instance, divergence resulting from social fission and communicative isolation is less salient in states than in other forms of social organisation. Conversely, intensive borrowing and stable mixed languages are relatively recent phenomenon, due to factors such as state-driven migration. I’d definitely recommend reading it.