Much of the work I plan to do for this year involves integrating traditional and contemporary theories of language change within an evolutionary framework. In my previous post I introduced the concept of degeneracy, which, to briefly recap, refers to components that have a structure-to-function ratio of many-to-one, with a single degenerate structure being capable of performing distinct functions under different conditions (pluripotent). Whitcare (2010: 5) provides a case in point for biological systems: here, the adhesin gene family in A. Saccharomyces “ expresses proteins that typically play unique roles during development, yet can perform each other’s functions when expression levels are altered”.

But what about degeneracy in language? For a start, we already know from basic linguistic theory forms (i.e. structures) are paired with meanings (i.e. functions). More recent work has expanded upon this notion, especially in developing the concept of constructions (Goldberg, 2003): “direct form-meaning pairings that range from the very specific (words or idioms) to the more general (passive constructions, ditranstive construction), and from very small units (words with affixes, walked) to clause-level or even discourse-level units” (Beckner et al., 2009: 5). When applied to constructions, degeneracy fits squarely with work identifying language as a Complex Adaptive System (see here) and as a culturally transmitted replicator (see here and here), which offers a link between the generation of first order synchronic variation – in the form of innovation (e.g. newly introduced linguistic material in the form of sounds, words, grammatical constructions etc) – and the selection, propagation and fixation of linguistic variants within a speaker community.

For the following example, I’m going to look at a specific type of discourse-pragmatic feature, or construction, which has undergone renewed interest over the last thirty-years. Known as General Extenders (GEs) – utterance- or clause-final discourse particles, such as and stuff and or something – researchers are realising that, far from being superfluous linguistic baggage, these features “carry social meaning, perform indispensible functions in social interaction, and constitute essential elements of sentence grammar” (Pichler, 2010: 582). Of specific relevance, GEs, and discourse-pragmatic particles more generally, are multifunctional: that is, they are not confined to a single communicative domain, and can even come to serve multiple roles within the same communicative context or utterance.

It is proposed the concept of degeneracy will allow us to explain how multifunctional discourse markers emerge from variation existent at structural components of linguistic organisation, such as the phonological and morphosyntactic components. If anything, I hope the post might serve as some food for thought, as I’m still grappling with the applications of the theory (and whether there’s anything useful to say!).

Using a mostly hypothetical example, which is somewhat informed by the general literature, I’ll look at three types of structure (S) that are characteristic of GEs in English, namely: and things like that (S1), and stuff like that (S2) and and stuff (S3).

Each of the examples (taken from Cheshire, 2007) are just to show you how GEs might occur in spoken discourse. I’ll only refer sporadically to the specific instances of use, but it’s good to take note of how these different forms operate, especially the similarities and differences between their functional properties, and the semantic and pragmatic contexts within which they are situated. The emphasis, then, is to try and address some important distinctions between redundancy (structure-to-function ratio of one-to-one), degeneracy (structure-to-function ratio of many-to-one) and pluripotential (structure-to-function ratio of one-to-many), and how we need to incorporate all three aspects to fully appreciate language as robust, evolvable and complex.

Scenario One: Redundant Replication

Now, with each of the above examples, we can easily envisage a scenario where there is structural redundancy: S1, for instance, could be repeatedly copied from speaker to hearer without a significant loss in structural fidelity at a morphosyntactic level. What’s produced is essentially a lineage of and things like that. Importantly, in a redundancy-only scenario, the function (F) also remains the same in transmission (I consider function here to refer to semantic and/or pragmatic elements). We can observe this extract 19: in this example, the GE highlights, or reinforces, the inference that roasts is part of a more general category of English food.

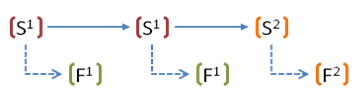

Redundancy is therefore highly robust: through the repeated duplication of structures and functions, a construction becomes stable within the linguistic system. As such, the loss of an idiolect, through migration, death or some other historically contingent factor within a speech community, is not concomitant with the loss of a construction. However, with this increased robustness comes a tradeoff in the system having low evolvability: as there is no inherent variability, change must come about through introducing a new structure and function (as we see in fig.1). Remember, in our toy example here, a change in either structure or function must be coupled, as we’re dealing with redundant-only systems.

Fig.1: GE structures (Sn) and their functions (Fn) in a redundancy replication scenario.

Scenario Two: Degenerate Replication

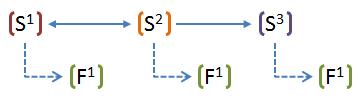

Extending on the redundant only scenario, degeneracy offers the possibility of a particular function, such the one outlined for extract 19, being distributed across several dissimilar structures, which in this case are S1, S2 and S3. Why is this advantageous over the previous scenario? Like redundancy, degenerate components are robust, as a single function is distributed across several structures, except this time the structures are different. As such, not only does high robustness exist in degenerate systems, but its accompanied by a high degree of evolvability: variation between several GE structures introduces the possibility for, to take one example, competitive amplification within a speech community. Importantly, the amplification of one GE over another can be achieved without a loss of function. To use an arbitrary, but perhaps historically justified, example is the possibility of the shorter form and stuff being selected and amplified at the expense of and stuff like that due to constraints of economy.

Fig.2: GE structures (Sn) and their functions (Fn) in a degeneracy replication scenario.

Scenario Three: Pluripotential Replication

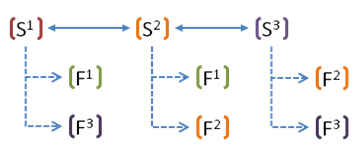

What we have in the last scenario is really a more realistic extension of the second: here, not only is there structural variability, but also multifunctionality. To keep it somewhat hypothetical, and relatively simplistic, imagine there exists three functions (treat these as toy examples): F1 = set marking tag; F2 = marks new information; F3 = indicates turn-taking. As before, there is a high degree of robustness and evolvability, except now it is advantageous to maintain several structures that, at times, perform the same function, but importantly S1, S2 and S3 can perform, either independently or simultaneously, additional functions depending on context. So, rather than having the competitive elimination of forms, there is now a pressure to maintain variation through retentive amplification.

Fig.3: GE structures (Sn) and their functions (Fn) in a pluripotential replication scenario.

To re-emphasise: we’re dealing with simplistic toy examples here — a lot of what I’m proposing being far from new, and a great deal further away from being fully fleshed out. As already alluded to a few paragraphs ago, it is well-attested that GEs are multifunctional, and considerable work has been done in developing and detailing theories of semantic and pragmatic change. My angle, or at least the angle I’m aiming for, is the furthering on the similarities between different evolutionary systems, namely: biological and linguistic. As Bill Benzon pointed out, we might find similar examples of degeneracy in stories and songs, and I would hazard a guess that the same holds true more broadly for technological and cultural evolutionary systems.

References

Cheshire, J. (2007). Discourse variation, grammaticalisation and stuff like that Journal of Sociolinguistics, 11 (2), 155-193 DOI: 10.1111/j.1467-9841.2007.00317.x

Whitacre, J. (2010). Degeneracy: a link between evolvability, robustness and complexity in biological systems Theoretical Biology and Medical Modelling, 7 (1) DOI: 10.1186/1742-4682-7-6

This is really interesting, and a great concrete example of degeneracy. I’ve noticed that second language learners often get taught general extenders as s1 type structures. However, beginner learners quickly adopt them as stock phrases and used to end sentences where the speaker can’t think how to express themselves (i.e. s3 types). However, in this case there is often no reduction in the form, but the speakers may well have re-analysed the phrase as a monolithic constituent.