Today I published a short commentary on a recent paper which found correlations between rice growing and collectivism (Talhelm et al., 2014). We’ve written about collectivism before (and here). However, while this may sound like a spurious correlation, there’s more to it: The theory is that communities which engage in more intensive practices, and therefore require help and collaboration of others, are biased towards a collectivist attitude (as opposed to an individualist attitude). Rice growing is more intensive than wheat growing, and requires more extensive irrigation, both of which may require collaboration from neighbours.

The really interesting thing about Talhelm et al.’s study is that they look at data within a single country – China. They also find correlations at the county level: Neighbouring counties which differ in the proportion of rice grown (the so-called rice-wheat border) differ in a range of sociological measures of individualism.

Still, the study did not directly control for possible shared history – either of farming practices or social attitudes. I was recently a reviewer for another commentary on the paper, and decided to look a little deeper.

As a test of spuriousness, I did a very quick comparison of the proportion of rice planted in US states. Higher rice vs wheat is correlated with higher collectivism (estimate = 7.9 collectivism points for a change in ratio of 1, p = 0.05). However, this is due to the same cause: the US has such a different culture, ecology, economy and time-depth. Indeed, since only 6 states produce any rice at all, the correlation is likely due to these outliers.

Since the original paper was published, new data and trees have become available which would make the relevant controls for shared history possible. In particular, a recent paper by Johann-Mattis List and colleagues builds a tree of historical relations between dialects spoken in China based on lexical data (see here, pdf here, data here). The trees are built using List’s LingPy program – an open source Python program which does world list processing, automatic cognate detection, borrowing detection and tree building. It’s quite an exciting tool and I’ll be using it in the future.

For my commentary, however, I just wanted to test whether linguistic differences also predict differences in farming practices. If so, this could indicate that farming practices (and possibly collectivism) is inherited or borrowed, casting doubt on the robustness of the original findings.

The data for the original study is available online. I compared differences in the proportion of rice grown in each province with the difference in the lexicon based on List’s data (using a Mantel test). There was a correlation between the two, suggesting that a phylogenetic study would be informative. I did the same test using ASJP data and found the same result.

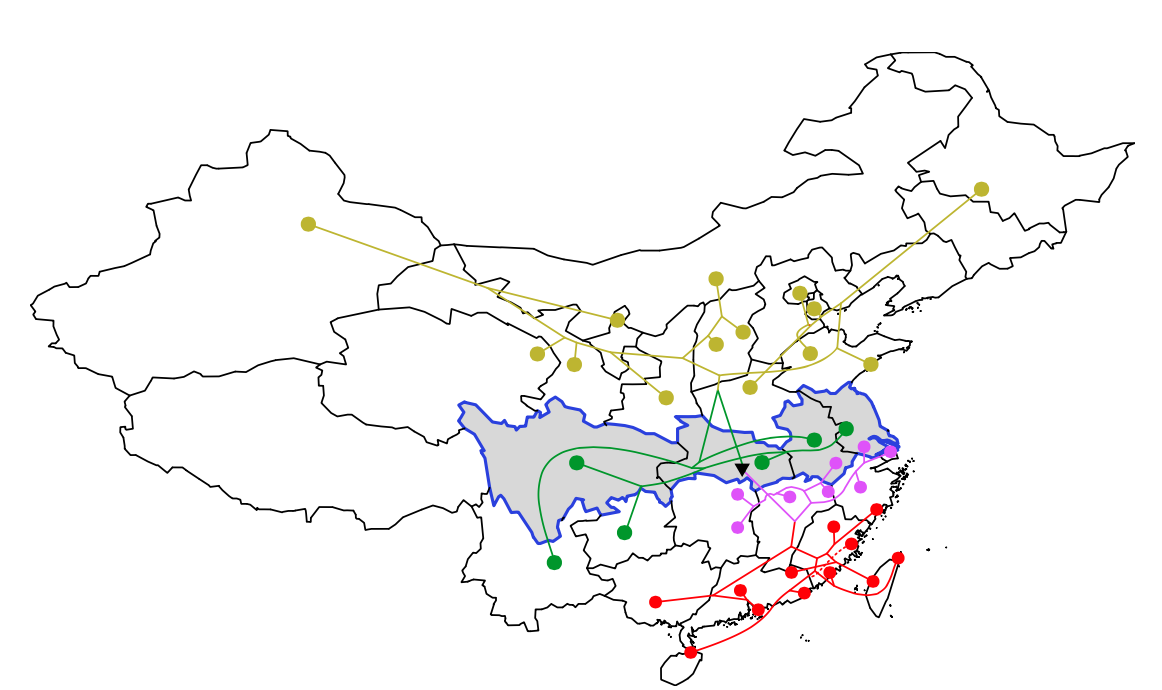

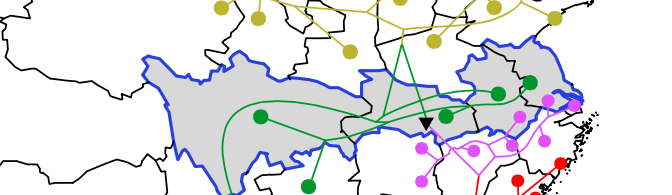

Here is a phylogenetic tree projected onto a Map of China (Figure 1 from the commentary, but not on the website yet, made using the R function phylo.to.map from phytools). The tree splits varieties in the north (low rice production) from the south (high rice production).

I end the commentary by suggesting that researchers considering cultural traits in many fields might consider collecting linguistic data, alongside anthropological, psychological and socioeconomic data, in order to run controls for shared history.

You mean vernacular dialects not languages, Chinese is one written language with various spoken dialects

Oops, good point. In the article I mostly talk about ‘varieties’, though I slipped up in the graph. (I speak a language which is often assumed to be a dialect of English, so I know how annoying this is!).

I’ve no idea why you’re calling Chinese varieties ‘dialects’, when under a reasonable definition of a language on intelligibility criteria, they are different languages. In Chinese are referred to as 方言 ‘dialect’, but arguably for political reasons, and should not dictate English usage of that word. Unless I’ve misunderstood your sentence in some way.

Usually when people say language, they mean something that is written differently

The shared writing system is certainly a better reason than politics to call Chinese varieties dialects.

However, ‘language’ as used by linguists refers normally to spoken varieties, making the details of the writing system irrelevant, as most languages are not written. The criteria used to count languages is mutual intelligibility, i.e. the fact that Cantonese, Minnan, Mindong, etc. are mutually unintelligible means they are different languages, and this is how a standard site on languages such as Glottolog would count it. This may therefore differ from the semantics of 方言 in Chinese, but as I said the English word ‘language’ and ‘dialect’ are used differently (e.g. English dialects, dialect continua).

The shared writing system point is also a little misleading; obviously when Cantonese is written it has morphemes such as 喺which are not used in Mandarin. When most Chinese varieties are written down, they use vocabulary closer to Mandarin, creating the illusion of greater similarity in the writing than there should be. A related point is that classical Korean is written in Chinese characters, without the authors knowing any Chinese; the written form does not have to that closely tied to the spoken form.

I mean, it’s also the history, which I don’t know if you can say is political. People can say that Norwegian and Swedish are pretty similar and could be viewed as one language, but they are not, because of their history and that they’re written differently.

One Western analogy to the situation in China is how educated Europeans used to speak Latin in official settings, whether it’s classical, church Latin, neo Latin etc, but there would be various vernacular dialects that evolved into languages like Spanish, when vernacular spelling became codified.

I think when people say it’s political, it’s that Mandarin medium education has really spread over the past 60 years or so, similar to how Latin education spread in Europe historically, and older people in dialect areas feel that something is lost when their kids only learn Mandarin in school.

I suppose that is what i mean when I say that the use of ‘dialect’ is partly political; the fact that China is one country, the use of Mandarin as a standard language, and the fact that most varieties are not written down or are written using Mandarin-ised vocabulary. The shared writing system is a better reason for describing Chinese as one language with many dialects, if ‘language’ is defined more broadly as a communication system with mutual intelligibility, whether it is spoken or written. However, I still think in the way that linguists use ‘language’, in order to be consistent it refers to spoken varieties and mutual intelligibility, e.g. when we say there 7000 languages in the world, it follows therefore that Chinese is at least 7 different languages.

I agree with you in this respect, just presenting a different perspective. I would say a lot of people say like, varieties