![]() Ok, so I was going to write an essay for my Origins of Language module on this but then got distracted by syntax (again) so I thought I’d put my thoughts in a blog post just so they don’t go to waste.

Ok, so I was going to write an essay for my Origins of Language module on this but then got distracted by syntax (again) so I thought I’d put my thoughts in a blog post just so they don’t go to waste.

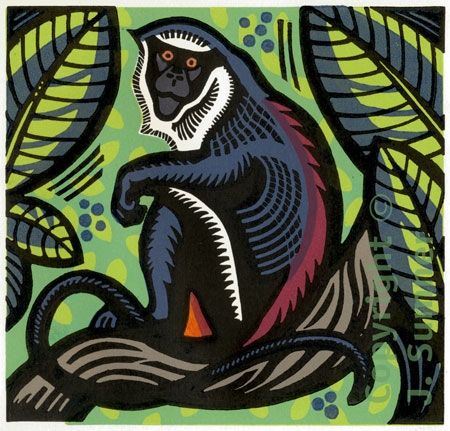

Diana monkeys, like vervet monkeys, use alarm calls to communicate the presence of a predator to other monkeys.

They produce (and respond to) different alarm calls corresponding to how close the predator is, whether the predator is above or below them and whether the predator is a leopard or an eagle. They respond instantly regardless of how imminent an attack is.

In this post I will explore some of the evidence relating to how sophisticated the Diana monkey’s understanding of the call’s meaning is and also the mental mechanisms relating to the call’s production.

Zuberbühler (2000a) discusses some types of species which have alarm calls but instead of each alarm call representing a different predator, each alarm call represents a different level (or types) of danger. The aim of the Zuberbühler paper then, was to set out if this was the case for Diana monkeys or if they really did have referential ‘labels’ for different predators.

Methods (Zuberbühler, 2000a)

Zuberbühler (2000a) found his Diana monkeys in the Tai National Park. The groups of monkeys were not habituated to human presence. The tests were done only on monkeys which were not aware of the presence of any humans. Speakers were positioned in the vicinty of the monkeys. These speakers were either ‘far away’ or ‘close’, ‘above’ or ‘below’ and the sound emitted was either that of a leopard growling or an eagle shrieking. Each group of monkeys was only tested once.

11 groups of Diana monkeys heard eagle shrieks and 12 hear leopard growls. These were both ‘close’ and ‘far away’ in equal numbers in each condition and also ‘below’ and ‘above’ in roughly equal distribution. (apparently leopards hang around in trees (up to 25m up) and eagles hang around the ground sometimes so this wouldn’t throw the monkeys as much as you’d think).

Diana monkey responses were then recorded. Different calls can be distinguished by a difference in duration (both presyllabic inhalation, duration of syllables themselves, intersyllabic duration and overall duration), frequency of glottal pulses and formant positions and transitions throughout.

In order to assess which of the independant variables had an effect on the calls Zuberbühler (2000a) compared the calls with respect to the above and produced an ‘r squared’ value which is the percentage of variance.

Results (Zuberbühler, 2000a)

Zuberbühler (2000a) found that not only did the predator’s elevation and distance have an effect on the calls but also the categorisation of “leopard” vs. “eagle”.

Playback studies.

So Diana monkeys have internal referential ‘categories’ of both ‘leopard’ and ‘eagle’ but how long do these stay in their minds? Zuberbühler has also done quite a few playback studies whereby he primes the monkeys with a leopard or eagle call (this doesn’t even have to be a Diana monkey call, he has done it with Campell monkeys’ calls too and the Diana monkeys act appropriately (bilingual monkeys!!!) (Zuberbuhler, K. ,2000b)), after five minutes, upon hearing a leopard growl or eagle shriek the monkeys will respond much more quietly. This is presumably because they still have the knowledge that there’s a predator about and so presume everybody still knows from last time and does not want to bring attention to itself when there’s predators about.

Problems

Zuberbühler (2000a) himself points out that using leopard growls and eagle shrieks is not the most ideal way of conducting this kind of experiment as neither species would normally emit such sounds when hunting. They are, apparently, more effective than things like motionless predator models though and also allow the experimenter to control variables such as distance, time delay, intensity and duration. Using vocalizations also ensures that all of the Diana monkeys learn of a predator at approximately the same time as each other.

I also have a problem with the priming studies because, although they show the monkeys are reacting differently (more quietly) after a five minute period, I am not convinced that this is evidence of the monkeys holding in their mind knowledge of a specific predator. It may just be as a result that they know that themselves and the rest of the monkeys are in an appropriate safe position away from the predator and so such a strong call may not be needed. That is to say their weak reaction is as a result of their position as opposed to their memory of the last call. I know it’s nice to give the monkey the benefit of the doubt but you have to be objective about these things.

References

Zuberbühler K (2000a). Referential labelling in Diana monkeys. Animal behaviour, 59 (5), 917-927 PMID: 10860519

Zuberbuhler, K. (2000b). Interspecies semantic communication in two forest primates Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 267 (1444), 713-718 DOI: 10.1098/rspb.2000.1061

Interesting post!

The questions about the functional referentiality of Monkey alarm calls and what kinds of mental representations are really interesting. I recall that James Hurford had an interesting Discussion of alarm calls in his 2007 book the Origins of meaning. His main point seems to be that in alarm call-producing monkeys there is no distinction between declarative and the procedural/performative aspects:

I totally agree with you that it is important not to be very careful in what kinds of mental representations to attribute to alarm-producing animals. I’m particularly sceptical about the claims by Con Slobodchikoff that prairie dogs have about 100 ‘words’ and can encode things like size, shape, and even colour in their alarm calls (see also language log, here and here).

Yeah this post was sort of born out with a discussion I was having with Jim Hurford. (He’s running the Origins of Language module). I need to read more about Vervets. For some reason I’ve started with Diana Monkeys who are probably less famous.

I hadn’t read this about Prairie dogs before. Thanks for the heads up. Rico the dog can understand 200 words! http://kobi.nat.uni-magdeburg.de/uploads/Courses/Kaminski_etal_Sci04.pdf – I thought that was pretty spectacular.

Could understand, I’m afraid :(. I went to a talk by Julia Fischer a couple of months ago, who said that he died some time ago. Seems like he’s joined the illustrous club of passed-away language-trained animals, like Nim Chimpsky, Washoe or Alex…

Oh I am sad to hear that. 🙁