In phonetics and phonology there is an important distinction to be made between sounds that can be broadly categorised into two divisions: consonants and vowels. For this post, however, I will be focusing on the second, and considered by some to be the more problematic, division. So, what are vowels? For one, they probably aren’t just the vowels (a, e, i, o, u) you were taught in during school. This is one of the big problems when teaching the sounds systems of a language with such an entrenched writing system, as in English, especially when there is a big disconnect between the sounds you make in speech and the representation of sound in orthography. To give a simple example: how many different vowels are there in bat, bet, arm, and say? Well, if you were in school, then a typical answer would be two: a and e. In truth, from a phonological standpoint, there are four different vowels: [æ], [e], [ɑː], [eɪ]. The point that vowel-sounds are different from vowel-letters is an easy one to get across. The difficultly arises in actually providing a working definition. So, again, I ask:

What are vowels?

One generally stated view comes from a phonetic viewpoint, where vowels are sounds “in which there is no obstruction to the flow of air as it passes from the larynx to the lips” (Roach, 2009, pg. 10). Okay, that seems to be a fair enough analysis, with vowels like ah! [ɑː] and oh! [oʊ] presenting an unobstructed view. Meanwhile, consonants like [s] and [d], as in the words stop and dog, quite clearly impede the airflow from passing through the mouth. However, there are instances where consonants are produced without much of a constriction in the vocal tract. The approximants [j] and [w] are good illustrations of this: try saying yes and wet to see what I mean by the clear lack of impediment. This leads us to the conflict between the phonetic definition of a vowel (a sound produced with no constriction in the vocal tract) and the phonological definition (vowels form the nucleus of syllables). In the above example, yes and wet are vowel-like in phonetic terms, yet they satisfy the phonological criteria of being consonants in that they form the syllable onset. Again, there are problems with accepting the phonological definition over the phonetic one, such as the syllabic l, but I’ll cover these problems in the post on syllables.

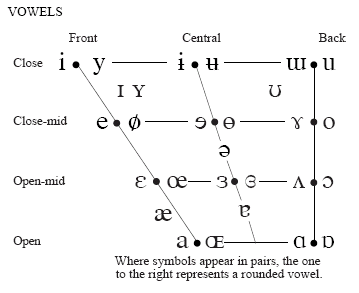

It seems, then, that a more parsimonious definition is one in which “the most important difference between vowel and consonant is not the way that they are made, but their different distributions” (ibid, pg. 11). Linguists also want to know about the ways vowels differ from each other. A useful delineation is to consider the relative shape and position of the tongue:

It is useful to simplify the very complex possibilities by describing just two things: firstly, the vertical distance between the upper surface of the tongue and the palate and, secondly, the part of the tongue, between front and back, which is raised highest.

For example, the [æ] vowel in cat, bat, or pat is considered to be a open front vowel: that is, it’s a vowel where there is a great deal of distance between the surface of the tongue and the roof of the mouth (hence, open), with the tongue being highest at the front of the mouth. The quadrilateral shape below shows what are known as the cardinal vowels. The vowels here don’t directly correspond to any particular language; instead, they are a reference point for the range of vowels that the human vocal apparatus can make. Classifying sounds in this manner is useful for describing, classifying and comparing vowels across and within languages. The pairing of vowels simply corresponds to roundedness: vowels on the left side of the pairing are unrounded, whilst those on the right are rounded. So, to return to our [æ] example: it is in fact a (near-)open front unrounded vowel.

We can now move onto the last section of this post: short vowels.

English Short Vowels

As you will discover in later posts: the length of vowel sounds are constrained by the context within which they are used. For our current purposes, however, we can consider vowel sounds in isolation as being differentiated by their length. In the case of English, there are six short vowels: [ɪ], [ɛ], [æ], [ʌ], [ɒ], [ʊ]. Borrowing heavily from Peter Roach’s brilliant book, English Phonetics and Phonology, I’ll now show the context in which these vowel sounds appear (along with a transcription):

- [ɪ] (example words: bit /bɪt/, pin /pɪn/, fish /fɪʃ/).

- [ɛ] (example words: bet /bɛt/, men /mɛn/, yes /jɛs/)

- [æ] (example words: bat /bæt/, man /mæn/, gas /gæs/)

- [ʌ] (example words: cut /kʌt/, come /kʌm/, rush /rʌʃ/)

- [ɒ] (example words: pot /pɒt/, gone /gɒn/, cross /krɒs/)

- [ʊ] (example words: put /pʊt/, pull /pʊl/, push /pʊʃ/)

There is one last short vowel that I’ve not yet mentioned, known as the schwa [ə]. This is heard in the first syllable of words like about /əbaʊt/ and oppose /əpoʊz/. It is normally kept separate from short vowels for several theoretical and observational purposes — and is something I’ll touch upon later on. In the next post, I’ll introduce three additional vowel concepts: long vowels, dipthongs and tripthongs.

Of course, regional variation has to be taken into account. In my speech (American Midlands accent, Maryland), the [ɒ] words have an unrounded vowel, there’s no distinction between [ʌ] and [ə], and “pull” is definitely not [pʊl].

Too true. I feel slightly stupid for not mentioning variation, as it’s the topic of one my next posts. Thanks.