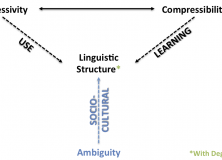

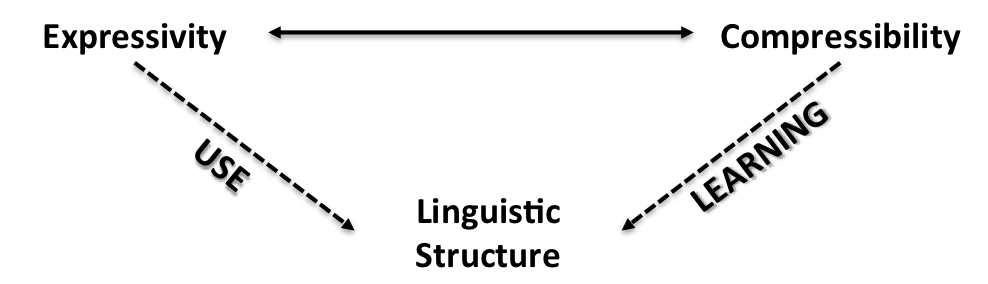

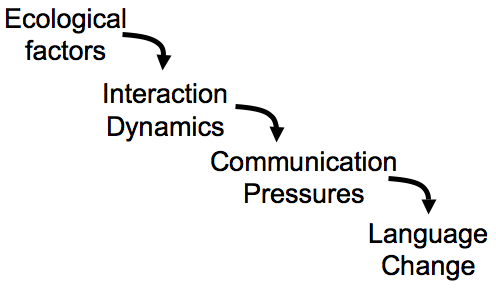

Two weeks ago my supervisor, Simon Kirby, gave a talk on some of the work that’s been going on in the LEC. Much of his talk focused on one of the key areas in language evolution research: the emergence of the basic design features that underpin language as a system of communication. He gave several examples of these design features, mostly drawn from the eminent linguist, Charles Hockett, before moving on to one of the main areas of focus over the past few years: compositionality (the ability for complex expressions to derive their meaning from the combined meaning of their parts; see Michael’s post and Sean’s post for some good previous coverage). Simon’s argument is that compositionality, as well as some other design features of language, emerge from two competing constraints: a pressure to be useful (expressivity) and a pressure to be learned (compressibility).

The general gist of the talk was that by varying the relative pressures of these two constraints we can evolve very different systems of communication. To get something approaching language we thus need to reach a balance between learning and use. First, naïve learning is required because it forces language to adapt to the learning bottleneck imposed by the maturational constraints on child learning. Still, even with this inter-generational learning pressure, language isn’t merely a passive task of remembering and reproducing a set of forms and meanings. Instead, we need to also account for usage dynamics: here, the system must display a capacity to be expressive, in so much that there is an ability for signals to differentiate between meanings within a language.

From Kirby, Cornish & Smith’s (2008) work we know that a language heavily biased towards maximally expressivity is very much like the initial generation of their experiments: there is an idiosyncratic set of one-form to one-meaning pairs without any systematic structure. It’s expressive because every possible meaning in the space has a label. By contrast, a stronger bias towards learnability results in highly compressible languages: that is, we see highly underspecified systems of communication, with the most extreme example being one-form to all-meanings. The result of balancing these two forces over Iterated Learning (henceforth, IL) is the emergence of compositionality: a learnable, yet highly structured communication system that is the result of a pressure to generalise over a set of novel stimuli.

Continue reading “Degeneracy emerges as a design feature in response to ambiguity pressures”