Children are better than adults at learning second languages. Children find it easy, can do it implicitly and achieve a native-like competence. However, as we get older we find learning a new language difficult, we need explicit teaching and find some aspects difficult to master such as grammar and pronunciation. What is the reason for this? The foremost theories suggest it is linked to memory constraints (Paradis, 2004; Ullman, 2005). Children find it easy to incorporate knowledge into procedural memory – memory that encodes procedures and motor skills and has been linked to grammar, morphology and pronunciation. Procedural memory atrophies in adults, but they develop good declarative memory – memory that stores facts and is used for retrieving lexical items. This seems to explain the difference between adults and children in second language learning. However, this is a proximate explanation. What about the ultimate explanation about why languages are like this?

I have previously blogged about a theory by Hagen (2008) which sees this distinction in memory as adaptive to small, isolated populations in early humans. I tried to modify the theory by claiming that the adaptation was to different social tasks for children and adults (MacWhinney, 2001), and even went to the trouble of building a stupidly complex model of it all. However, I recently realised that this was the wrong approach.

Language changes to fit the cognitive niche of its learners (Christiansen & Chater, 2008), so the question should really be why are some aspects of language more easily learnable with procedural memory? That is, why has language adapted to procedural memory users? The simple answer is that the learners of language are usually children – if they cannot learn aspects of the language, those aspects will not be passed on. This creates a selective pressure on language to adapt to children. And since children are still in the process of developing declarative memory, aspects which are easily encoded by procedural memory are selected for.

So, here’s the hypothesis: Children favour procedural memory aspects such as morphology while adults would favour declarative memory aspects such as lexical forms of distinction. For example, a child may prefer morphological marking of the future tense (in Spanish hablo: I speak, hablaré: I will speak ) while an adult prefers lexical marking (as in English I speak, I will speak). This creates a prediction – that a language with many adult learners will tend to use lexical means of distinction rather than morphological.

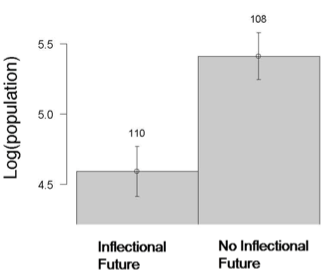

There is some support for this. Lupyan & Dale (2010) conducted a large-scale statistical analysis of the world atlas of languages (see posts here and here). They found that languages with many speakers spread over a large area and with many adult second-language learners tended to be less morphologically complex than languages spoken by small, contained, isolated communities. Below is a graph from Lupyan & Dale (2010) which shows that whether a language marks the future tense morphologically can be predicted by the language community’s population (Wintz also shows that there’s a link between population size and phoneme inventory size).

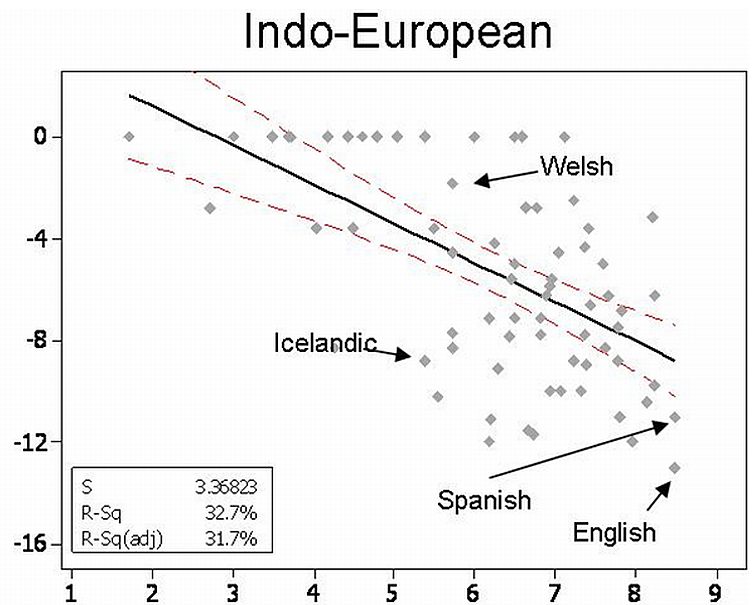

More generally, a population’s size is correlated with an index of morphological complexity. Below, we see that languages like English which is spoken by many people across the globe and has many second language speakers (it may now have more second language speakers than native speakers) scores very low on the morphological complexity scale.

The x-axis is log population, the y-axis is a morphological complexity score (the number of features for which each language relies on lexical versus morphological coding subtracted from 1).

This agrees with my prediction. Lupyan and Dale do state that

“the most frequent typologies … correspond to those known to be more easily learned by children whereas typologies common to high-population (i.e., exoteric) languages are those that are best learned by adults.”

However, they don’t explicitly invoke the procedural/declarative memory model. In doing so, we can make further predictions: Any demographic change that results in an imbalance between procedural and declarative memory abilities will affect the selection pressure on language. For example, because alcohol damages procedural but not declarative memory, there may be differences in the language of cultures that traditionally drink beer to those that drink tea (suggested by my collegue Eric Johnstone).

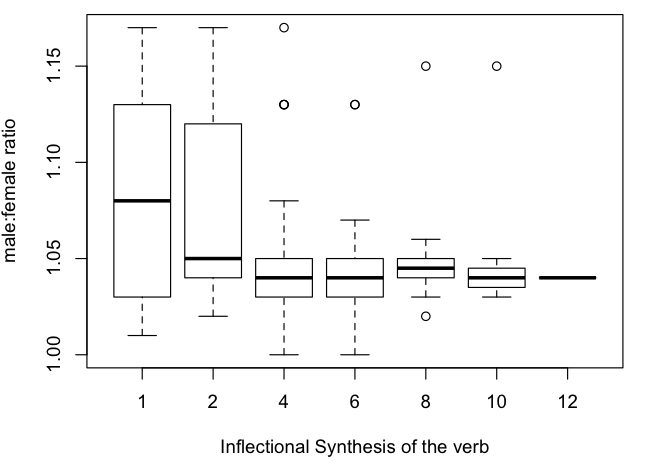

Also, females are better than males at tasks requiring declarative memory (Hartstone & Ullman, 2005). So, we’d expect a population with more females to have less morphological complexity. Using the World Atlas of Language Structures, and sex-ratio data from Wikipedia, I tested this and to my surprise found a significant negative correlation between sex ratio and the inflectional synthesis of the verb (134 languages, r = -0.17, p < 0.05):

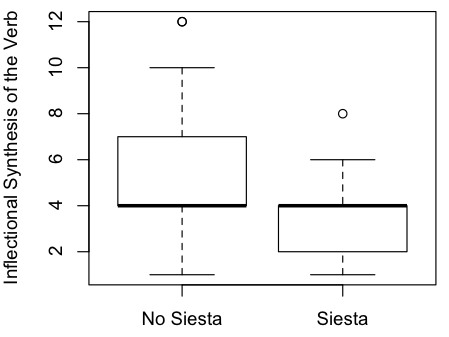

Other research shows that daytime naps improve procedural memory (Backhaus & Junghanns, 2006). So, cultures which take siestas may have adults with better procedural memory, shielding the language from a lexical selection bias. In fact, countries that take siesta (as listed on Wikipedia) have languages with less morphological complexity than countries that do not take siesta (134 languages, t = 3.47, p =0.001):

Astute readers will note that these are in fact the opposite of what I predicted. Backhaus and Junghanns also find that females regularise more than males, which is not what they initially expected, and I’m still trying to get my head around their explanation.

At any rate, the statistics above should not be taken too seriously (Wikipedia data is highly suspicious and the actual data processing was done on a train from Krakow to Warsaw) and I’m not controlling for many aspects (language phylogenies, latitude, wars etc.). They do suggest, however, that there may be something worth exploring here.

I conclude with a tentative hypothesis: Different languages may depend differentially on different brain structures because of functional pressures. That is, languages may be radically different from each other given the different needs of the population. In fact, because the function of language is so different in different cultures, a general theory of language may be so abstract that it is just the theory of Evolution. Biologists come up against this problem too: the theory of Evolution is pervasive, but a particular adaptation needs to be studied in terms of its context. How should linguists incorporate this approach? Taking a nap after lunch seems to be a good starting point.

L. Kirk Hagen (2008). The bilingual brain: Human evolution and second language acquisition Evolutionary Psychology, 6, 43-63

Lupyan G, & Dale R (2010). Language structure is partly determined by social structure. PloS one, 5 (1) PMID: 20098492

Christiansen, M., & Chater, N. (2008). Language as shaped by the brain Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 31 (05) DOI: 10.1017/S0140525X08004998

Hartshorne JK, & Ullman MT (2006). Why girls say ‘holded’ more than boys. Developmental science, 9 (1), 21-32 PMID: 16445392

BACKHAUS, J., & JUNGHANNS, K. (2006). Daytime naps improve procedural motor memory Sleep Medicine, 7 (6), 508-512 DOI: 10.1016/j.sleep.2006.04.002

the theory of Evolution is pervasive, but a particular adaptation needs to be studied in terms of its context

I agree that this also applies to language. And I like the clever thinking on the notion that imbalances between procedural and declarative memory will affect the selection pressure on language. Still, I wonder if there is some general signature of selection, as in biological evolution, to distinguish between aspects of languages that are adapting and those that are drifting. I suppose one ideal way would be to assign fitness values to particular utterances. Those utterances that rapidly spread through a population show signs of selection, whereas differences in frequency between utterances may just be the result of exposure to a particular variant (equivalent to bio drift)… Really, I’m just repeating the work of William Croft and others.

Say hi to your “colleague” Eric Johnstone – haven’t heard from him in a while. Icelandic as a second language and morphological complexity…I don’t get the scale of the graph – can you elaborate what it’s based on really (seriously!)?

Wintz – good point about drift. I’ll have to moderate my claims.

Rags – you’re right, I didn’t label the graph. The particular languages in the graph were picked out by the original authors.

Along the bottom is the log population and up the side is a morphological complexity score. This score is based on “the number of features for which each language relies on lexical versus morphological coding”, based on features such as number of case markings, number of grammatical categories on the verb, possessive markings, number of distinctions in adpositions, distinctions of possibility and evidentiality and inflectional synthesis of the verb.

I agree that this score seems to be a bit arbitrary, and many languages will have fairly unique ways of making distinctions (e.g. Welsh marks gender by mutating initial consonants). Some of the gaps were filled in using regression analyses (most likely values given the other languages). However, this result is robust when the analysis is done with all languages, by language family and by geographic area.

Icelandic is a language spoken by few people who are relatively isolated and it has very few second-language speakers. It should, according to the theory, be very morphologically complex.

What about Russian? High consumption of alcohol, lots of people using it as a second language (parts of Eastern Europe and Central Asia), complicated morphology…

zhp – Good point, there will doubtless be outliers, and we’re talking about very small biases. However, there are several languages spoken in Russia, with a range of morphological complexity. Just on the synthesis of the verb there is:

Ket (1)

Nenets (2)

Chukchi (4)

Stanard Russian (4)

Evenki (6)

Hunzib (6)

Adyghe (8)

Nivkh (8)

Ingush (10)

The real problem is not having enough fine-grained data on sex ratio or alcohol consumption – it’s not really good enough to have one datapoint for a country the size of Russia! Lupyan & Dale had much finer data on population size.

The thing is, how do you suppose this whole idea actually works? In real life? It’s not that adult people are suddenly seized by the desire to learn English based purely on its morphological simplicity. In the Middle Ages, Latin was probably the widest-spoken second language, and its morphology 1)is relatively complicated; 2) doesn’t seem to have ungergone much change because of so many people learning it.

I think you have the causality the wrong way around- the idea is that aspects of language which are more difficult to learn are less likely to be passed on to the next generation of speakers. If a language can express something morphologically and lexically (e.g. in English you can form the past tense of ‘I blog’ as ‘I blogged’ or ‘I did blog’), then adults learning this system are more likely to use the lexical form more often. So any adults learning from them are even more likely to use only the lexical form. Over several generations, this small bias will compound until the language is very different. This isn’t my idea, but based on many researcher’s work such as Morten Christiansen, Nick Chater and Simon Kirby.

Classical Latin has indeed been preserved, mainly because of it’s importance in written literature. However, languages do change over time – Italian is just Latin that’s undergone change.

The development of analytical tendencies over time is a feature of all Indo-European languages, as well as the tendency for favouring regular forms over irregular, but it is hard to see this direct casuality based on differences in memory, gender makeup of the population or alcohol consumption.

I’m not following regular forms being favoured over irregular.

Highly frequent verbs maintain irregularity whereas less frequent are analogically formed. Also, frequent usage of what may be considered an irregular form can produce analogical (regular) paradigms. Regularity is a question of diachronic perspective.

Sean,

What do you think of Hagen? I have his second language acquisition book buried in a pile waiting to be read. Does he do justice to language evolution in your opinion?

Jonathan – I don’t know anything about Hagen’s general work on language acquisition, but I gave a talk about Hagen’s theory concerning language evolution recently (and will give another on the 8th of October at Edinburgh). The problem is that he tries to infer things about social structure of very early societies from the structure of memory. He argues that the atrophy of procedural memory in adults is evidence that there was no selective pressure for second language learning in adulthood. There are a few problems with this:

1) The atrophy of procedural memory is more likely linked to general decline of cognitive plasticity, while the later development of declarative memory may be linked to different non-linguistic social pressures on adults and children (MacWhinney, 2008 – children need to gain protection and adults need to find mates and co-ordinate for hunting).

2) Cultural evolution changes language faster than biological evolution changes genes. It’s therefore more likely that language adapted to our memory constraints rather than the other way around (Christiansen & Chater, 2008).

3) There is archaeological evidence for group interaction: Hirchfield (2008) is a reply to Hagen (2008) and brings up some inconsistencies.

4) Hagen argues that linguistic diversity suggests that early communities were isolated, but recent research suggests that linguistic diversity doesn’t entail isolation (G.Roberts, 2010, Nettle & Romaine, 2000).

In short, I think Hagen has the wrong end of the stick. Hagen is not alone in this – Chater & Christiansen (2010) have recently urged the field of language acquisition to keep language evolution in mind (see my post here ). However, I can’t find any other papers about evolution and the capacity to learn more than one language.