In my two previous posts (here and here) about imitation and social cognition I wrote about experiments which showed that

1) young children tend to imitate both the necessary as well as the unnecessary actions when shown how to get at a reward, whereas wild chimpanzees only imitate the necessary actions.

And that

2) both 14-month old human infants as well as enculturated, human raised-chimpanzees tend to ‘imitate rationally.’ That is, they tend to be able to differentiate whether an agent chose a specific way of performing an action intentionally, or whether the agent was forced to performing the action in this specific manner by some constraint.

The fact that human-raised chimpanzees also show this sensitivity suggests that enculturation plays an important part in this process.

In a very interesting study, Range et al. (2007) used an experimental setup similar to that of Gergely et al. (2002) (which i described in my second post, here) to test whether other ‘enculturated’ and domesticated animals show the same kind of sensitivity: dogs.

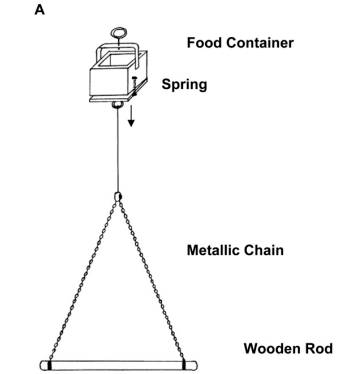

Range et al. (2007) presented dogs with an apparatus that required them to pull down a wooden rod, which then caused a food container to spring open so that the dogs got a food reward.

Range et al. (2007) presented dogs with an apparatus that required them to pull down a wooden rod, which then caused a food container to spring open so that the dogs got a food reward.When presented with this apparatus, dogs preferred to pull down the wooden rod wih their mouth.

What Range et al. (2007) were interested in was to see whether dogs would be influenced by seeing a “demonstrator dog” pull down the rod in a specific way before manipulating the apparatus themselves.

T

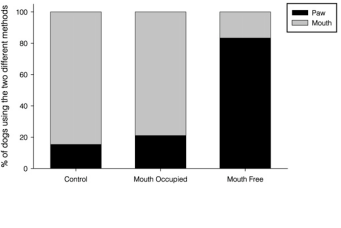

o test this, they trained an adult female dog to pull down the rod with their paw instead of using the preferred mouth action. Then in the experiment, two groups of “test dogs” first watched the “demonstrator dog” pulling the rod with her paw. In the first group the “demonstrator dog” carried a ball in her mouth, which “justified” using the non-preferred way of pulling down the rod.

In the second group however, she didn’t have a ball in her mouth. In this group then, no external constraint could explain why she chose this specific way of pulling the rod.

When the “test dogs” could manipulate the apparatus themselves, the dogs in the “Ball”/Mouth Occupied-Group did not imitate the way the demonstrator dog had pulled down the rod during their first attempt, but instead used the prefered way of pulling the rod with their mouth. Dogs in the “No Ball”/Mouth Free-group, however, used their paw to pull the rod in their first attempt of manipulating the apparatus, thus imitating the ‘demonstrator dog”s way of getting at the reward.

This means that dogs, just like 12-14 month old children and enculturated chimpanzees, tend to imitate rationally and selectively.

That is, dogs in the second group somehow inferred that the demonstrator dog’s way of pulling down the rod was somehow relevant, whereas dogs in the first group interpreted the demonstrator dog’s way of performing the action as the result of external constraints.

In their article, Range et al. state that is still an open question whether these results stem from dog’s evolutionary history as domesticated or their from their enculturation by humans. The correct answer is probably that both factors have an effect on dog’s capacitiy/motivation for imitation. But, as I mentioned above, the fact that enculturated chimpanzees also imitate rationally, whereas wild chimpanzees do not, suggests that enculturation is a very powerful influence in the development of social cognition. (see also Lyn et al. in press)

References:

Range F, Viranyi Z, & Huber L (2007). Selective imitation in domestic dogs. Current biology : CB, 17 (10), 868-72 PMID: 17462893

I find the evolution of dogs fascinating. I’ve spent a lot of time researching, trying to figure out how they saw man as companion/hunter/savior–whatever–that they would abandon their primal roots. It’s hard to believe it has only been the last 10-12k years, though that’s what research shows. I prefer to think early man–Homo erectus–enjoyed the company of dogs.

Great study. Thanks for sharing.

Kaminsky et al failed to replicate these results, however they ran an importatnt control condition which suggest that dogs cannot differentiate between rational and irrational acts. They have a low(er) level interpretation of the results. You should check this paper:

http://email.eva.mpg.de/~braeuer/pdf/Kaminski_et_al_2011.pdf