This week our paper on future tense and saving money is published (Roberts, Winters & Chen, 2015). In this paper we test a previous claim by Keith Chen about whether the language people speak influences their economic decisions (see Chen’s TED talk here or paper). We find that at least part of the previous study’s claims are not robust to controlling for historical relationships between cultures. We suggest that large-scale cross-cultural patterns should always take cultural history into account.

Does language influence the way we think?

There is a longstanding debate about whether the constraints of the languages we speak influence the way we behave. In 2012, Keith Chen discovered a correlation between the way a language allows people to talk about future events and their economic decisions: speakers of languages which make an obligatory grammatical distinction between the present and the future are less likely to save money.

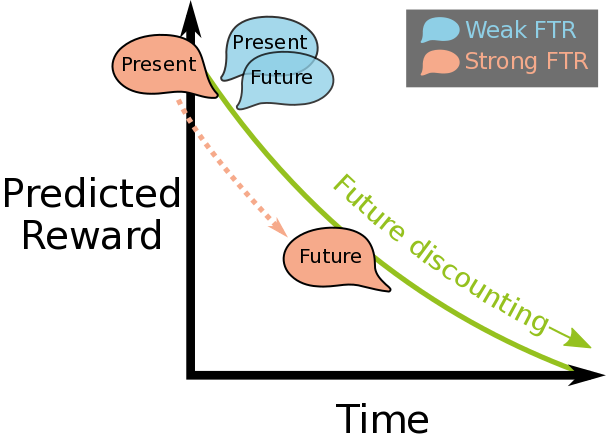

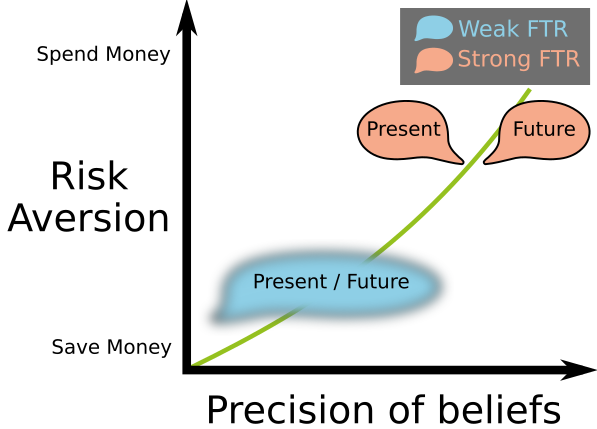

The general theory is that obligatory linguistic distinctions force speakers to think in a certain way which may influence their behaviour. Chen proposed two mechanisms by which the link with economics could come about. First, a constant pressure to mark the present tense as different from the future makes the temporal future seem further away by contrast. This would lead to a discounting of the potential reward in the future for a cost paid in the present and therefore bias a speaker to spend rather than save (saving money is risky, since you’re delaying a known reward in the present for an unknown reward in the future). Put another way, if the future seems further away, you are less concerned with preparing for the future.

The second hypothesised mechanism suggests is that a constant pressure to mark the present tense as different from the future could lead to more precise mental partitioning of time. This could lead to more precise beliefs about the exact point in time when the reward for saving would be higher than the reward for spending. The economic model in Chen’s original paper demonstrates that a more precise belief about the timing of a reward leads to greater risk aversion. This suggests that individuals with more precise beliefs would be more willing to spend money now rather than risk a possibly smaller reward in the future.

In the paper we review some studies which demonstrate that language can influence speakers’ perception of time. However, Chen’s study differed from many previous ones: it used a survey of hundreds of thousands of individual people, rather than an experiment or a typology of languages, and it linked language with long-term, important decisions instead of short-term processing biases.

Controlling for cultural history

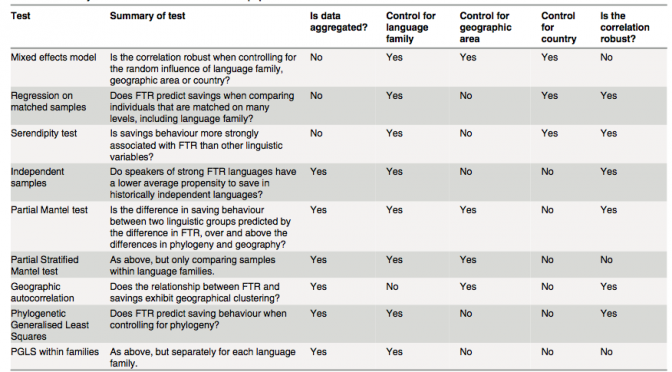

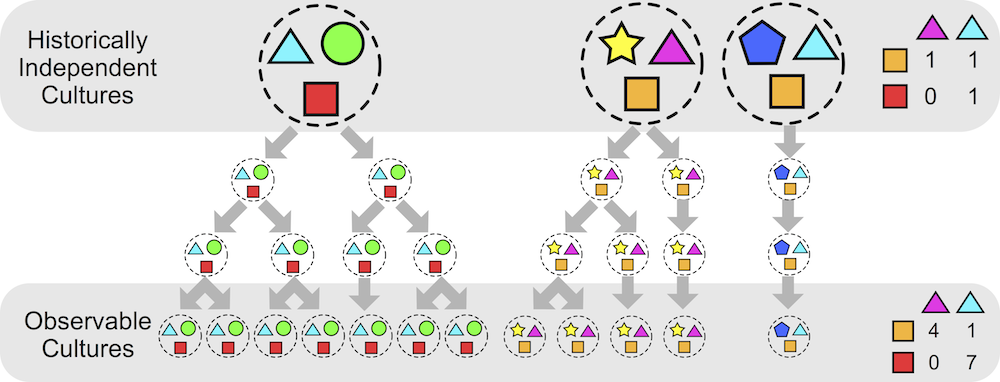

Linking economic behaviour and language could have a big impact on public policy, as well as theories in linguistics and economics. Therefore it is important to make sure that the correlation is real and not an artefact of big data analyses. One problem with looking at large samples of cross-cultural data is that some cultures are historically related, meaning that the data points are not strictly independent (see the work by James and me on spurious correlations). For example, The UK and Germany have similar cultures, languages and economy due to trade and cultural contact. It might therefore be unfair to count them as two independent data points. This is called ‘Galton’s problem’, (see figure below). In this paper, we run a series of analyses that attempt to control for this non-independence.

The graph below, taken from the paper, demonstrates how spurious correlations can be caused by cultural inheritance:

At the top are three independent historical cultures, each of which has a bundle of various traits which are represented as coloured shapes. Each trait is causally independent of the others. On the right is a contingency table and there is no particular relationship between the colour of triangles and the colour of squares. However, over time these cultures split into new cultures. Along the bottom are the currently observable cultures. We now see a pattern has emerged in the raw numbers (pink triangles occur with orange squares, and blue triangles occur with red squares). The mechanism that brought about this pattern is simply that the traits are inherited together: there is no causal mechanism whereby pink triangles are more likely to cause orange squares (more here).

In our paper, we attempt to test whether Chen’s correlation can be explained by this process.

Big data

It may seem easy to test this correlation. Over two years ago, I wrote a blog post about an initial statistical test. However, the analysis was quite complicated. Indeed, the structure of the data was so complicated, we uncovered a bug in the standard R package for mixed effects modelling! (it’s being addressed here)

The challenge was to link behavioural data from individuals (whether they saved money or not) with population-level data from languages (whether they mark the future tense). We use a number of methods, but the best solution was mixed effects modelling. This tried to predict the behaviour of individuals while controlling for the bias from historical relations.

The original study suggested that speakers of weak FTR languages were 30% more likely to save money. When controlling for historical relatedness, the effect size was only about half as strong, and not significantly different from chance. Essentially, countries with similar economic conditions also had languages which were related, and therefore had similar grammatical structures, boosting the apparent correlation.

Furthermore, after the initial submission of the paper the World Values Survey, from which the individual-level data comes, released a new wave of results. We re-analysed this and discovered that the relationship between tense and saving becomes weaker as data is added. This contrasts with other variables such as employment status which increase in statistical strength as more data is available.

Alternative explanations

There were several other criticisms of Chen’s paper, such as the suitability of the distinction between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’, questions about confounding variables, bilingualism and so on. While all of these alternative explanations are valid, in our paper we wanted to ask a very simple question: is obligatory future tense correlated with reduced propensity to save when controlling for historical relatedness?

It’s a strange paper in the sense that it tries hard to find a negative result. Still, we think that the kinds of methods used in our paper should be applied to any study attempting to demonstrate a correlation between cross-cultural variables.

Progress

An over-simplistic story would be that Chen was wrong. However, the findings are quite complicated and the general theory is far from disproved. The correlation was robust to some other analyses such as a replication of the original regression on matched samples. Furthermore, Chen’s original study and some follow-ups also looked at other aspects such as diet and smoking and other sources of data such as the use of the future tense in weather reports and average bank account savings. The influence of language on economics may be real, but proving it will require a consideration of cultural history.

Ultimately, large-scale cross-cultural statistics may not constitute the best evidence for or against Chen’s theory. In this case, a psycholinguistic experiment could quite easily be done (and I’m in the early stages of working with a PhD student to try to do this). Indeed, not only might an experiment have more explanatory power, it might be quicker and easier to do: this paper asked whether two variables were correlated, and it took nearly 3 years to write and includes 7 different statistical methods and 116 pages of supplementary materials!

More interesting, I think, is that Chen put his money where his mouth is and tried testing the previous finding to breaking point in the name of science. Both James and I have been very impressed with Chen’s attitude throughout our collaboration: Chen has been engaged and open and just interested in finding out the answer, rather than defending a pet project. In an age where funding is often won by hype and prestige, this demonstrates that it’s still possible to be faithful to basic scientific practice: find a pattern, try to explain it, then try to confirm or rule out your explanation with data.

Many others helped us along the way, but particularly crucial to this project was the input of Bodo Winter, who provided overwhelmingly helpful advice and suggestions.

A clear positive message from this paper is that collaboration is good for science. The phenomenon under investigation spanned linguistics, economics and statistics, and would be impossible to do without expertise in each area. Hopefully, future studies which seek to demonstrate correlations in large-scale cross-cultural data will pay attention to the kinds of biases uncovered in this paper.

In the next post I hope to get into the nitty-gritty of the methods!

Roberts SG, Winters J, Chen K (2015) Future Tense and Economic Decisions: Controlling for Cultural Evolution. PLoS ONE 10(7): e0132145. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0132145

This is a wonderful piece of work. And, yes, cultural evolution should be taken into account.

Excellent. Now I am thrilled to see if media will be as interested this time as when Chen published his original study.

All copies of the WALS database should be deleted from the internet and any remaining hard copies (in whatever format) should be buried in concrete bunkers deep under the earth. This seems to be necessary to prevent naive young researchers from ruining their lives by publishing overelaborate hypotheses based on the oversimplified garbage found in WALS.

I agree that there’s a bit of a goldrush which might lead some to make hasty conclusions. However, I think that making data public is a good idea, though we haven’t yet quite caught up with methods to deal with so much of it. While easily accessible data makes it easier to find misleading correlations, it also makes it easier to refute them.

Also, just a note: Chen’s study was not based on WALS data. It was based on typological data from the Eurotyp project and a survey of hundreds of thousands of people from the World Values Survey.