Textbooks are boring. In most cases, they consist of a rather tiring collection of more or less undisputed facts, and they omit the really interesting stuff such as controversial discussions or problematic cases that pose a serious challenge to a specific scientific theory. However, Martin Hilpert’s “Construction Grammar and its Application to English” is an admirable exception since it discusses various potential problems for Construction Grammar at length. What I found particularly interesting was the problem of “meaningless constructions”. In what follows, I will present some examples for such constructions and discuss what they might tell us about the nature of linguistic constructions. First, however, I will outline some basic assumptions of Construction Grammar.

In Construction Grammar, constructions are defined as form-meaning pairings at various levels of abstraction. Probably the most well-known definition of a construction goes back to Goldberg (1995: 4):

C is a construction iffdef C is a form-meaning pair <Fi, S> such that some aspect of F, or some aspect of Si is not strictly predictable from C’s component parts or from other previously established constructions.

In addition, Goldberg (2006: 5) argues that “patterns are stored as constructions even if they are fully predictable as long as they occur with sufficient frequency.” Thus, we can distinguish two conditions determining construction status: a) the non-compositionality condition, b) the frequency condition. The latter is, however, quite controversial (cf. e.g. Stefanowitsch 2009 for discussion). In addition, there is some debate about the lowest level of abstraction. For example, Croft (2001) and Goldberg (2006) posit morpheme constructions, while Booij (2010) argues that bound morphemes cannot be seen as constructions in their own right. Some, like Diessel (forthc.), reserve the term “construction” for units that are not lexically specific, using the Saussurean term “sign” as a hyperonym for lexically specific items and “constructions” in this narrower sense. I prefer using the term in the broader sense for reasons which will hopefully become clear in the remainder of this post. Most importantly, I think that a word is arguably the most prototypical example of a non-compositional pairing of form and meaning. While it is true that some distinction should be made between lexically specific items and more abstract constructions (which is the main motivation for the distinction between lexical items and “constructions”), I will argue below that the boundary between both is seriously blurred.

This might seem quite counterintuitive. One could object that it is quite straightforward to deal with lexically specific items as facts of language use, while “construction” is first and foremost an interpretive, heuristic notion. In contrast to a word like “dog”, an abstract construction like the transitive construction does not “exist”. Instead, it is a generalization over many instantiations of the transitive construction. These concrete realizations are called “constructs”. One could argue now that a lexical item is a generalization over different instantiations, as well: A word like “dog” will evoke a slightly different mental simulation in every speaker, and even in a population of speakers using the same variety of a language, there might be subtle differences in the pronunciation of the word. Thus, assuming that a word like dog “exists” is as much an idealization as assuming that the transitive construction “exists”. But even if we agree that we have to assign a fundamentally different status to lexically specific items than to more abstract constructions, we are faced with a variety of questions, e.g.: When is a frequent combination of lexical items with specific features so frequent that language users draw a generalization over these instances of language use? When is a combination of lexical items so frequent that it counts as a lexically specific unit in its own right (as could be argued for many idioms)?

While questions like these are widely discussed, the basic definition of a construction is fairly uncontroversial: A construction is a pairing of form and meaning. However, as Hilpert (2014: 50-57) points out, there is considerable debate about the question whether all constructions have meaning. While it is fairly easy to posit an abstract meaning for e.g. the ditransitive construction, it seems much harder to find meaning in constructions such as the so-called filler-gap construction in (1) or the shared completion construction in (2) (examples from Hilpert 2014):

(1) One sock lay on the sofa, the other one under it.

(2) The South remains distinct from and independent of the North.

Gapping and shared completion constructions can be seen as elliptic constructions. As Hilpert (2014: 56) points out, they “have all the characteristics of traditional phrase structure rules, while not conveying any substantial meaning of their own.” Indeed, they can be seen as fairly regular patterns, but rather than conveying some kind of meaning by formal means, they are constituted by the systematic omission of (formal) material. In the first sentence, the verb is omitted in the second phrasal constituent; in the second one, “two adjectival phrases […] share a common ending” (Hilpert 2014: 54). Inserting the omitted elements does not entail a change in meaning:

(1′) One sock lay on the sofa, the other one lay under it.

(2′) The South remains distinct from the North and independent of the North.

Hilpert (2014: 57) points out that “Construction Grammarians need to face the critical evidence of patterns such as SHARED COMPLETION, GAPPING, and STRIPPING in order either to save the current idea of the construct-i-con or to adapt the theory in an ad-hoc way to accommodate the empirical facts. […] The worst that Construction Grammarians could do would be to look the other way, towards nice meaningful patterns such as THE X-ER THE Y-ER or the WAY construction, and pretend that the problem of meaningless constructions does not exist.”

The relevant question, however, can be framed in various ways: a) Are these constructions really entirely meaningless or do they, after all, entail an ever so slight change in meaning? b) Can we conceive of a viable definition of constructions which does not posit meaningfulness as a necessary condition? (Note that this question relates to the non-compositionality debate mentioned above.) c) If so, how would this alter our conceptualization of the constructicon, i.e. the structured network of constructions that constitues language users’ linguistic knowledge? – I will address these questions in turn.

Same but different? The meaning of meaningless constructions

If we want to face the problem of meaningless constructions, we must first come to terms with the notion of “meaning”. Generations of linguists have struggled with the definition of this seemingly quite straightforward and self-explanatory term. However, I won’t delve too deeply into different theories of meaning and their history, but rather outline how I conceptualize “meaning” from a cognitive-linguistic point of view. Most cognitive linguists (and most construction grammarians, for that matter) agree that meaning can be unserstood in terms of embodied mental simulation. For instance, a word like wug serves as a prompt for mentally simulating a wug – if you know what a wug is, that is. Your mental simulation will of course crucially depend on your experience with wugs. The same goes for action terms: If you’re a programmer (or a corpus linguist), you will probably have a more accurate understanding and a more lively representation of a term like binge coding than an armchair linguist or a carpenter. In terms of Cognitive Grammar, meaning is “encyclopedic” (cf. Langacker 1987; Taylor 2002, 2003), i.e. the meaning of a linguistic expression depends on our knowledge about the concept which the expression denotes. In the emerging field of experimental semantics, more and more support for this view of meaning has been gathered. Bergen (2012) provides a good overview of much work in this field.

But given this view of meaning, how can we say that a construction like the ditransitive construction has “meaning”? – Some well-known examples illustrate that syntactic constructions do indeed modulate the meaning of the lexical material inserted into the respective “slots”. Consider a sentence like John baked Mary a cake, in which Mary is easily identified as the (intended) recipient of the cake, or Goldberg’s (1995) much-discussed illustration of the caused-motion construction: She sneezed the foam off the cappuchino. In both cases, it seems reasonable to assume a specific image schema evoked by the construction. Thus, the two sentences John gave Mary the book and John gave the book to Mary are not exactly synonymous, but differ in their construal of the situation. Psycholinguistic studies lend support to this analysis (cf. Bergen 2012: 107f.).

Image-schematic meaning (as we might call it) is of course different from “conceptual” meaning. This intuition is reflected in various distinctions that have been proposed in the literature. For example, Langacker (1987, 1991, 2008) distinguishes between the “conceptual content” of an expression and its “construal”. Langacker’s notion of construal is roughly identical to Talmy’s principle of “conceptual alternativity”, which he defines as the “cognitive capacity to construe an ideational complex in a range of ways” (Talmy 2000: 14). Talmy also makes a distinction between the semantics of open-class elements such as nouns and verbs on the one hand and closed-class elements such as prepositions or inflectional affixes on the other.

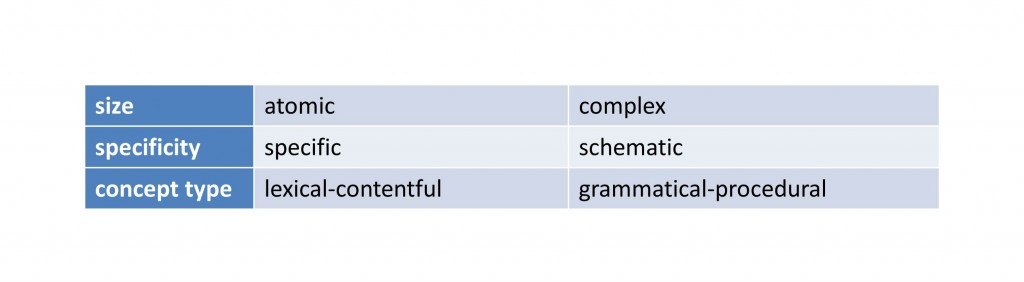

These distinctions are also reflected in the continuum of concept types proposed by Traugott & Trousdale (2013). They distinguish between lexical-contentful and grammatical-procedural constructions, adopting Terkourafi’s (2011: 358f.) definition of conceptual vs. procedural meaning:

[L]inguistic expressions can directly contribute concepts, that is, constituents of conceptual representations, in which case they encode CONCEPTUAL meaning; or they can contribute information about how to manipulate and combine these concepts into a conceptual representation. In the latter case, linguistic expressions encode PROCEDURAL meaning.

The dimension of concept type complements the defining properties of constructions as proposed by Croft (2001), who sees constructions as differing in size (atomic vs. complex) and phonological specificity (substantive vs. schematic). While nouns or adjectives like red are treated as contentful constructions by Traugott & Trousdale (2013: 12), plural -s or subject-auxiliary inversion are considered procedural constructions. The way construction (She elbowed her way through the crowd) is allocated between these two poles. In an evolutionary perspective, contentful constructions can be regarded as primary and thus “basic”, while procedural meaning emerges through usage factors. As Pleyer & Winters (2014: 35) point out, “repetition, chunking and expansion provide the raw material through which procedural functions can arise.”

Not all linguists share the assumption that procedural meaning is actually meaning. Regarding affixation patterns – which, in most cases, can be allocated towards the ‘procedural’ end of the continuum -, Marchand (1969: 215) famously stated that a bound suffix “has no meaning in itself, it acquires meaning only in conjunction with the free morpheme which it transposes.” According to Spencer (2001: 227), certain morphemes such as the so-called cranberry morphs “can be said to be meaningful only by stretching the meaning of ‘meaning’ rather uncomfortably”. Intriguingly, however, Spencer (ibid.) extends the notion of “meaningless morph” to cases such as morphologi-cal, nav-al, and poet-ic, as these adjectives “are really no different from the basic nouns but used in the syntactic contexts where an adjective is needed”. Indeed, on first glance, the suffixes don’t seem to do much more than saying, “Hey, I’m an adjective”. But actually, this seemingly simple syntactic transposition requires a major shift in construal. In addition, if we take the usage-based assumption that “[m]eaning is use” (Tomasello 2009: 69) seriously, any word-formation product will almost necessarily develop nuances of meaning that set it apart from its base: It is used in different contexts, exhibits different collocational preferences, etc. – all these aspects feed into its “meaning” in the broad sense.

In what has come to be one of the most influential illustrations of the notion of construction, Croft (2001: 18) sees the (conventional) meaning of a construction as composed of semantic, pragmatic, and discourse-functional properties. One example for the conventionalization of discourse-functional properties is the “What’s X doing Y” construction discussed by Bybee (2010), e.g. What’s that fly doing in my soup?, What are you doing with this knife? In this case, a simple Wh-question with doing has acquired a conventional implication of disapproval (cf. Bybee 2010: 27f.). Importantly, each usage event can modulate the coneptualization evoked by a linguistic unit. On the lexical level, we can find similar developments. Virtually every instance of semantic change can be attributed to such processes of dynamic meaning construal in interaction.

Now I have sketched two complementary approaches to meaning: The hypothesis of meaning as mental simulation and the hypothesis of meaning as use (for the latter, cf. e.g. Taylor 2012; Evans 2014). Both hypotheses might suggest that “empty” constructions differ in meaning from their “filled” counterparts. If the hypothesis that “meaning is use” is correct, it seems straightforward to assume that “empty” constructions are tied to specific discourse-pragmatic contexts. For instance, I would hypothesize that the shared completion construction is a feature of conceptually written language.

Being tied to specific contexts or registers is of course not an aspect of meaning per se, but it arguably adds certain element to our conceptualization of whatever the respective utterance conveys. Consider subject-predicate inversion in non-interrogative German main clauses, which marks the utterance as a joke: Kommt ein Mann in ne Bar ‘Comes a man into a bar’. (Cf. also the notorious joke Kommt ‘ne Frau beim Arzt ‘Comes a women at the doctor’s’, which makes use of the fact that German jokes frequently begin with Kommt ein(e)…). The additional text-pragmatic information conveyed by the construction governs our conceptualization of the conceptual content in question. From the point of view of the meaning-as-mental-simulation hypothesis, an additional argument in favor of a difference in meaning between “empty” and “filled” constructions can be put forward: As Bergen (2012) demonstrates, there is much evidence that in language processing, mental simulation takes place “early and often”. Garden path sentences are a nice illustration of what he calls incremental mental simulation: When comprehending a sentence like “The horse raced past the barn fell”, we just can’t wait patiently until the end of the sentence before we start mentally simulating the situation. Instead, mental simulation takes place right from the start – which is why we are surprised when we find that our initial conceptualization was partially wrong. Thus, we could argue that sentence (1) assigns less prominence to the position of the sock (lying instead of e.g. hanging) than (1′) since (1′) explicitly invits us to conceptualize “lying” or a “lying” image schema once again, whereas (1) relies on the common ground already established in the first phrasal constituent.

To be sure, stating that there is a difference between the meaning of construction A and the meaning of construction B does not mean that both constructions necessarily have meaning themselves – given that the assumption that constructions “have” or “carry” meaning is not a misconception itself. This leads us directly to the next issue.

Is meaningfulness a necessary condition for construction status?

The obvious answer seems to be Yes: If a linguistic unit or a specific configuration of linguistic units does not evoke or modify a certain conceptualization, there is no reason to call it a construction. However, matters are more complex. Apart from the examples mentioned by Hilpert (he actually mentions a lot more, but for all others, he provides good reasons to analyze them as meaningful constructions), some more examples come to mind in which the criterion of meaningfulness seems to prove problematic. Even on the lexical level, some items seem to be “meaningless”. For instance, the most widespread and de-facto standard grammar book of German explicitly treats conjunctions like dass ‘that’ as meaningless (Duden-Grammatik 2006: 632). For its English cognate that, the argument in favor of an analysis as a completely meaningless item seems even more straightforward, given that in many contexts, it can be omitted: I promise [that] I will provide a good argument soon; I told you [that] he’s a nerd. This seems to run counter to the strong hypothesis put forward e.g. in Cognitive Grammar that every symbolic unit carries meaning. On the other hand, language users are aware of the function of German dass, as becomes clear from the quite productive elliptic dass construction expressing, among other things, incredulity or disapproval (examples from the deWaC corpus, Baroni et al. 2009):

(3) Dass die Leute immer CDU und SPD wählen müssen! 👿 (http://bit.ly/1BJGNlZ) ‘[+> I don’t understand] That people always have to vote for [the political parties] CDU and SPD!’

(4) Daß ich dem User Francois einmal absolut zustimmen würde! 😮 (http://bit.ly/1D0Z7eI) ‘[+> I didn’t expect] That I would ever completely agree with the user Francois!’

The procedural meaning of the conjunction can therefore be considered part of the language users’ constructional knowledge. Concerning English that, we might argue in favor of its procedural meaning drawing on sentence pairs like He said the mayor’s a bum vs. He said that the mayor’s a bum, in which that can be argued to have a “distancing” effect (cf. Langacker 2008: 444).

Another interesting case are proper names. It is almost a commonplace in linguistic onomastics that proper names “don’t have meaning”. Again, the validity of such a statement depends our your definition of ‘meaning’. In uttering or comprehending phrases like Hannah’s experiment, James’ blog, Michael’s burger, I do have a conceptualization of Hannah or James or Michael in mind, which is decisive for a linguistic unit to have meaning according to the meaning-as-mental-simulation hypothesis. What sets proper names apart from appellatives is that they (ideally) refer to one specific concrete entity rather than a class of entities (cf. Nübling et al. 2012: 17f.). Therefore, the meaning of dog is, at first glance at least, very different from the meaning of James. Most importantly, the experiences and associations I connect with a specific name are not shared by anyone else, while there is certainly a great amount of convergence between my conceptualization of dogs and anyone else’s, despite individual differences. This is tightly connected to another important distinction, namely the distinction between the linguistic knowledge of an individual speaker on the one hand and a population of speakers on the other. As Plag (1999: 8) points out, “a large overlap of lexical knowledge between speakers is necessary for language to work.” The same goes for constructional knowledge, although recent research has called attention to individual differences in the comprehension of specific constructions such as e.g. passives (cf. Dąbrowska & Street 2006; Dąbrowska 2012).

Scott-Phillips (2015: 21-26) has recently distinguished two meanings of ‘meaning’, which are tied to two different approaches to communication: Within a code model of communication, meaning is used “to refer to a signal’s (direct) function” (Scott-Phillips 2015: 159). From the point of view of the approach advocated by Scott-Phillips, namely the ostensive-inferential model as proposed by Sperber & Wilson (1995), meaning is defined in a narrower way, namely as referring to speaker meaning (Scott-Phillips 2015: 158). With Grice (1957), he emphasizes the “auto-deictic character” of conventional codes, i.e. “the fact that ostensive stimuli are effectively pointers to the very intentions that triggered their production in the first place.” (Scott-Phillips 2015: 23) A constructionist account of meaning, I would argue, has to incorporate aspects of both definitions. On the one hand, constructions (all kinds of constructions: the notion of construction could in principle be extended from linguistic constructions in the narrow sense to the much broader area of semiotics) have to signal their own signalhood (Scott-Phillips et al. 2009). Clouds “mean” rain only in a colloquial sense of the word, as they are not auto-deictic in the Gricean sense just outlined. On the other hand, however, speaker meaning is only one aspect of meaning. Equally important is the hearer’s (re)interpretation of what has been said. As Verhagen (2005: 7) remarks, “[t]he point of a linguistic utterance, in broad terms, is that the first conceptualizer invites the second to jointly attend to an object of conceptualization in some specific way, and to update the common ground by doing so.”

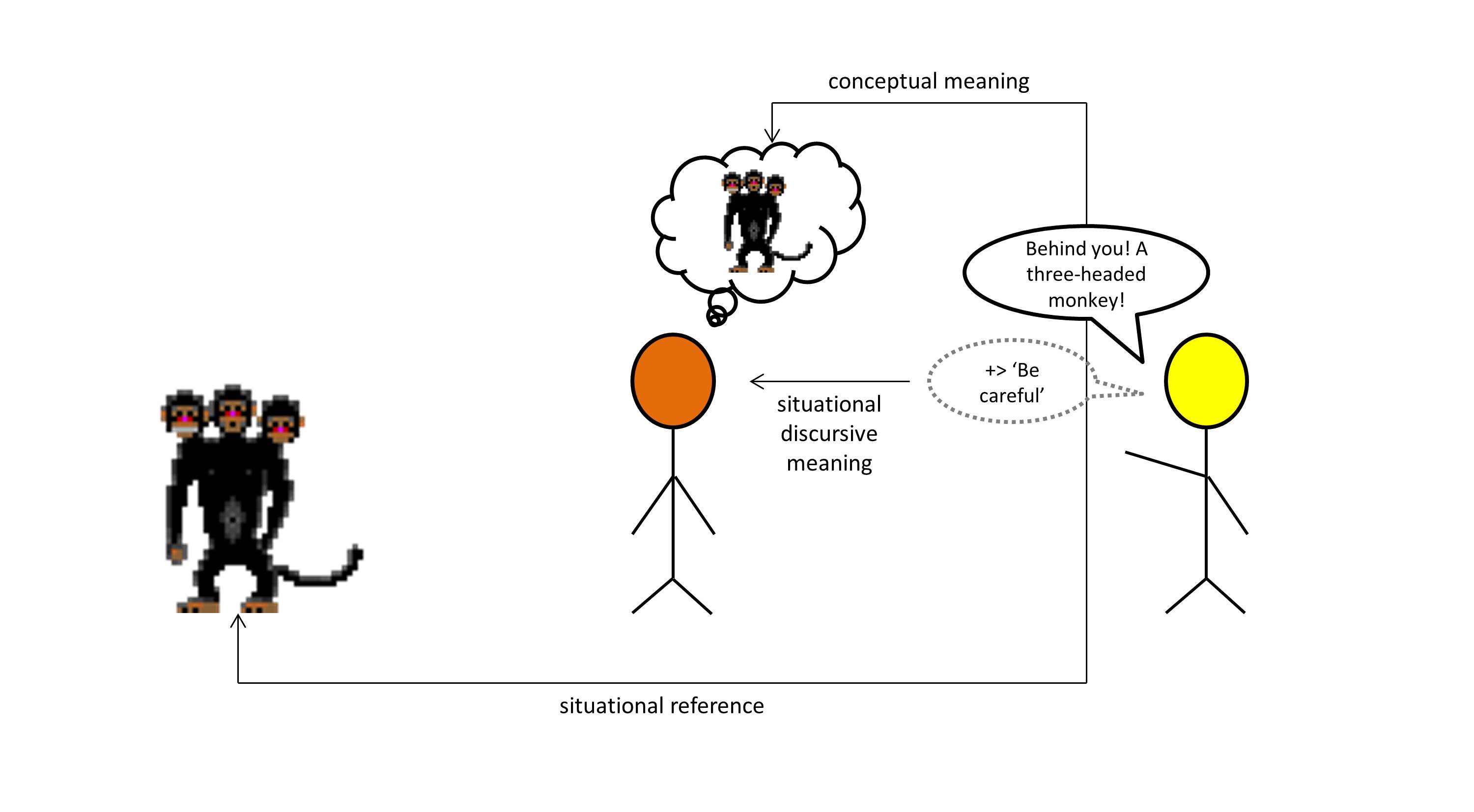

Returning to proper names, then, it seems straightforward to say that they are used to invite a conceptualizer to attend to an object of conceptualization. In a specific communicative setting, a proper name serves to identify an entity (e.g. a person, a town, a building) in a clear and unambiguous way. Thus, they do evoke a mental simulation, which makes them meaningful according to the meaning-as-mental-simulation hypothesis. In addition, proper names are easily recognized as such, as they tend to exhibit a variety of e.g. phonological and grammatical pecularities that set them apart from appellatives. And as for the meaning-as-use hypothesis: Even if you don’t know who James is, you will easily infer that I’m most probably talking about a human being (or, less likely, a pet). And when I talk about the Brocken, you might not know that it’s a mountain, but you probably have an ever so abstract idea that it must be some kind of entity: You don’t have a concept for it (yet), but you do know that it refers to something. Thus, we can distinguish between conceptual meaning on the one hand and referential meaning on the other. The latter is characteristic of, but not restricted to proper names. We can draw a more fine-grained distinction between situational and conventionalized referential meaning. James conventionally refers to a specific person, and appellatives like the sun or the moon conventionally refer to specific celestial bodies (unless of course I’m talking about the moons of Jupiter or the two suns of Tattooine). Expressions like this dog or The door on the left, by contrast, refer to a specific extralinguistic entity in a specific communicative situation, but not conventionally so – this dog can be a Dalmatian in one situation and a Chihuahua in another. As Construction Grammar seeks to capture generalizations (cf. e.g. Goldberg 2006), construction grammarians are particulary interested in the conventional meaning of linguistic signs, which of course often emerges from generalizations over situational meaning (cf. our discussion of the “What’s X doing Y” construction above).

Another potentially problematic case are formulaic expressions like Hello or Bye, which Langacker (2008: 475) calls ‘expressives’. As in the case of proper names, they often go back to expressions with a “lexical” meaning, e.g. French adieu < à Dieu (commant) ‘([I] command you) to God’. Langacker (2008: 475f.) argues that

For their part, expressives are not altogether lacking in descriptive content. They too invoke cognitive domains and impose a particular construal. […]

Like expressions used descriptively, expressives evoke conceptual content and direct attention within it. Among the cognitive domains invoked are interactive scenarios:

those of people meeting and exchanging greetings (for Hi, Hello, Greetings), of asking and answering a question (Yes, No), of helping one another and being polite (Please, Thanks, You’re welcome), and so on.

The “content” of expressives “is a facet of the interaction itself.” (Langacker 2008: 475). Langacker (ibid.) points out that many other expressions have “expressive or emotive import” as well, e.g. gay vs. queer, good vs. absolutely marvelous. Therefore, he argues that the difference between descriptive expressions and expressives is a matter of degree. Following his line of reasoning, we could say that expressives evoke “discursive” meaning. This is again very much in line with Scott-Phillips’ notion of “non-natural”/ostensive meaning.

The extensive discussion of some potentially problematic cases might have brought us a bit closer to what may be considered a constructionist theory of meaning, which is an important prerequisite for dealing with the problem of meaningless constructions. Summing up what we discussed so far, we can distinguish between different kinds of meaning which contribute to the overall meaning of a construction (both its conventional and its situational meaning):

- LEXICAL/CONCEPTUAL meaning refers to the conceptualization conventionally evoked by a linguistic construction.

- PROCEDURAL meaning refers to conventional patterns of construal and perspectivation imposed by an at least partly schematic linguistic construction.

- DISCURSIVE meaning refers to the (conventional or situational) expressive import of a construction in social-interactional contexts.

- REFERENTIAL meaning refers to the “signifying” relationship (in the Saussurean sense) between linguistic signs and extralinguistic entities.

Of course, these distinction are only heuristic in nature, as all these kinds of meaning interact in actual usage. Also, the list of different kinds of meaning may still be incomplete.

Returning to the empty constructions we started with, we can now check if they can be argued to have lexical, procedural, discursive, and/or referential meaning. Of course they don’t have lexical and referential meaning – what about procedural and discursive meaning, then? As mentioned above, we could argue that they evoke a slightly different conceptualization than their “filled” counterparts (procedural meaning) and that they might be associated with more formal communicative situations (discursive meaning). In addition, it could be argued that although these constructions “yield sentences with meanings that can be worked out by processing the meanings of the component words” (Hilpert 2014: 55), it is crucial to be aware of the convention that the meaning of one phrasal constituent is “filled up”, as it were, with the meaning of the other one. In this respect, shared completion is quite similar to simple coordination patterns, cf. e.g. a long and winding road: We know that both long and winding refer to the road. Thus, shared completion could also be treated as a non-prototypical case of coordination constructions. Gapping is a bit more peculiar in that the meaning of the first constituent is taken up again. But this, too, is not without parallel, cf. e.g. Some people in the bar were singing, the others dancing. Here, the others refers to the other people in the bar, relying on the common ground established by the first phrasal constituent. What is non-compositional about such constructions, then, is that they specify how the content of their constituents has to be combined. This is a matter of convention, and thus, not all ellipses are well-formed, cf. *One sock lay on the sofa, the other _____ under it. (In German, by contrast, the equivalent construction would be perfectly well-formed.) Could we thus assume something like (for lack of a better term) “metaconstructional meaning”? Well, we could, but that might really be tantamount to “stretching the meaning of ‘meaning’ rather uncomfortably”.

In addition, all this doesn’t answer the main question: Is it or is not a construction? And independently of that, does a construction necessarily require meaning? As Hilpert (2014: 57) points out,

purely formal generalizations, that is, constructions without meaning, have no natural place in the construct-i-con. In fact, if Construction Grammar is to be seen as a veritable theory of linguistic knowledge, then this theory will make the strong claim that there should not be any constructions without meanings. A scientific theory is usually considered ‘good’ if it makes claims that can be falsified. Construction Grammar is thus only a good theory of linguistic knowledge if it is clear what empirical observations could show that it is wrong.

In other words, Occam’s razor requires us to keep our theory as parsimonious as possible. Therefore, the idea that a language can be comprehensively described in terms of constructions is quite appealing since the notion of construction is a nice heuristic device that keeps theoretical preassumptions to a minimum: Starting from the very general idea that a construction is a form-meaning pair, the constructions constituting any language can be described in an empirical, bottom-up way. But constructions are more than heuristic devices – they are also hypotheses. As Bergen & Chang (2013: 169) point out, “each constructional form-meaning pair represents a hypothesis to be validated through observations of behavior in natural and experimental settings.” (Bergen & Chang 2013: 169) Likewise, as becomes clear from Hilpert’s quote, the idea that all units constituting any language in the world can be seen as constructions is a hypothesis.

But is it really a hypothesis that can be addressed empirically? I don’t have an answer to this question and I hope there will be a lively discussion in the comments section. Even though I’ve tried to disentangle the different notions of “meaning” a bit and to propose definitions that can be operationalized empirically, there remains a certain vagueness to the term. But let’s assume, for the sake of the argument, that we can and do prove empirically that there are constructions without meaning. Would this mean that “these […] patterns do not form part of the construct-i-con, as envisioned by current practicioners of the Construction Grammar framework” (Hilpert 2014: 57)? That the constructicon needs an “appendix”? Or would the notion of construction itself have to be modified?

One argument in favor of the latter approach might be that much in language seems to be “a matter of brute usage”, as Taylor (2012: 108) puts it. Constructions are, first and foremost, conventions. The preassumption that all conventions have to be meaningful, however, seems to make the theory less parsimonious – especially in a usage-based approach that sees language as a complex adaptive system, i.e. a system whose global behavior arises from local interactions among a large number of agents (cf. Frank & Gontier 2010: 37; cf. also Kirby 2012).

This is basically the flip side of the argument for compositional constructions (cf. the frequency condition discussed at the very beginning of this post): Just like a phrase such as I love you (discussed in Langacker 2005) can be seen as conventionalized patterns due to their high frequency, “meaningless constructions” could be seen as conventionalized combinatorial patterns that have become established in a population of speakers. This would still be in line with the idea that “a construction is a generalization that speakers make across a number of encounters with linguistic forms.” (Hilpert 2014: 9)

To sum up, then, I think that the notion of a construction as applied in “mainstream” Construction Grammar, i.e. defined as a form-meaning pairing with non-compositional/non-predictable properties, is an enormously helpful heuristic device in describing the structure of languages and in describing language change. However, it might be problematic to assume that all linguistic conventions can be described as meaningful. In addition, I’m not sure if this is actually a testable hypothesis, since finding any conterexamples crucially depends on your definition of “meaning”, which is, however, an incredibly vague notion. Note, however, that it is not only the notion that is vague – arguably, meaning itself is, by its very nature, vague and elusive. Scott-Phillips (2015) argues that underdeterminacy is an important design feature of language – thus, despite the generalizations that can be captured as “conventional meaning”, meaning is always in flux. It is always emergent from contextual and situational cues. Paraphrasing Hopper’s (1987: 148) well-known remark on grammaticalization, one could say that “there are no constructions, just constructionalization.”

If you’re not convinced by or not satisfied by my account, don’t worry – neither am I. But that’s exactly why I’m discussing it here…

References

Baroni, Marco, Silvia Bernardini, Adriano Ferraresi & Eros Zanchetta (2009): The WaCky Wide Web. A Collection of Very Large Linguistically Processed Web-Crawled Corpora. In: Language Resources and Evaluation 43 (3), 209–226.

Bergen, Benjamin K. (2012): Louder than Words. The New Science of How the Mind Makes Meaning. New York: Basic Books.

Bergen, Benjamin & Nancy Chang (2013): Embodied Construction Grammar. In: Thomas Hoffmann & Graeme Trousdale (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Construction Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 168–190.

Croft, William (2001): Radical Construction Grammar. Syntactic Theory in Typological Perspective. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dąbrowska, Ewa (2012): Different Speakers, Different Grammars. Individual Differences in Native Language Attainment. In: Linguistic Approaches to Bilingualism 2 (3), 219–253.

Dąbrowska, Ewa & James Street (2006): Individual Differences in Language Attainment. Comprehension of Passive Sentences by Native and Non-Native English Speakers. In: Language Sciences 28, 604–615.

Duden (2006) = Duden. Die Grammatik. 7th ed. Mannheim: Dudenverlag.

Evans, Vyvyan (2014): The Language Myth. Why Language is Not an Instinct. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Frank, Roslyn M. & Nathalie Gontier (2010): On Constructing a Research Model for Historical Cognitive Linguistics (HCL). Some Theoretical Considerations. In: Margaret E. Winters, Heli Tissari & Kathryn Allan (eds.): Historical Cognitive Linguistics. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 31–69.

Goldberg, Adele E. (1995): Constructions. A Construction Grammar Approach to Argument Structure. Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press.

Goldberg, Adele E. (2006): Constructions at Work. The Nature of Generalization in Language. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Grice, H. P. (1957): Meaning. In: The Philosophical Review 66 (3), 377–388.

Hopper, Paul J. (1987): Emergent Grammar. In: Proceedings of the Thirteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, 139–157.

Kirby, Simon (2012): Language is an Adaptive System. The Role of Cultural Evolution in the Origins of Structure. In: Maggie Tallerman & Kathleen R. Gibson (eds.): The Oxford Handbook of Language Evolution. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 589–604.

Langacker, Ronald W. (1987): Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. 1. Theoretical Prerequisites. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, Ronald W. (1991): Foundations of Cognitive Grammar. Vol. 2. Descriptive Application. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Langacker, Ronald W. (2005): Construction Grammars. Cognitive, Radical, and Less So. In: Francisco J. de Ruiz Mendoza Ibáñez & M. Sandra Peña Cervel (eds.): Cognitive Linguistics. Internal Dynamics and Interdisciplinary Interaction. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter, 101–159.

Langacker, Ronald W. (2008): Cognitive Grammar. A Basic Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Marchand, Hans (1969): The Categories and Types of Present-Day English Word Formation. A Synchronic-Diachronic Approach. München: Beck.

Nübling, Damaris, Fabian Fahlbusch & Rita Heuser (2012): Namen. Eine Einführung in die Onomastik. Tübingen: Narr.

Plag, Ingo (1999): Morphological Productivity. Structural Constraints in English Derivation. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter.

Pleyer, Michael & James Winters (2014): Integrating Cognitive Linguistics and Language Evolution Research. In: Theoria et Historia Scientiarum 11, 19–43.

Scott-Phillips, Thom (2015): Speaking Our Minds. Why Human Communication is Different, and How Language Evolved to Make It Special. London: Pelgrave.

Scott-Phillips, Thomas C., Simon Kirby & Graham R.S. Ritchie (2009): Signalling Signalhood and the Emergence of Communication. In: Cognition 113, 226–233.

Spencer, Andrew (2001): Morphology. In: Mark Aronoff & Janie Rees-Miller (eds.): The Handbook of Linguistics. Oxford: Blackwell, 213–237.

Sperber, Dan & Deirdre Wilson (1995): Relevance. Communication and Cognition. 2nd ed. Oxford: Blackwell.

Stefanowitsch, Anatol (2009): Bedeutung und Gebrauch in der Konstruktionsgrammatik. Wie kompositional sind modale Infinitive im Deutschen? In: Zeitschrift für Germanistische Linguistik 37, 562–592.

Talmy, Leonard (2000): Toward a Cognitive Semantics. 2 vol. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Taylor, John R. (2002): Cognitive Grammar. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, John R. (2003): Linguistic Categorization. 3rd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Taylor, John R. (2012): The Mental Corpus. How Language is Represented in the Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tomasello, Michael (2009): The Usage-Based Theory of Language Acquisition. In: Edith Laura Bavin (ed.): The Cambridge Handbook of Child Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 69–87.

Traugott, Elizabeth Closs & Graeme Trousdale (2013): Constructionalization and Constructional Changes. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Verhagen, Arie (2005): Constructions of Intersubjectivity. Discourse, Syntax, and Cognition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.