An article in PLos ONE debunks the myth that hunter-gatherer societies borrow more words than agriculturalist societies. In doing so, it suggests that horizontal transmission is low enough for phylogenetic analyses to be a valid linguistic tool.

Lexicons from around 20% of the extant languages spoken by hunter-gatherer societies were coded for etymology (available in the supplementary material). The levels of borrowed words were compared with the languages of agriculturalist and urban societies taken from the World Loanword Database. The study focussed on three locations: Northern Australia, northwest Amazonia, and California and the Great Basin.

In opposition to some previous hypotheses, hunter-gatherer societies did not borrow significantly more words than agricultural societies in any of the regions studied.

The rates of borrowing were universally low, with most languages not borrowing more than 10% of their basic vocabulary. The mean rate for hunter-gatherer societies was 6.38% while the mean for 5.15%. This difference is actually significant overall, but not within particular regions. Therefore, the authors claim, “individual area variation is more important than any general tendencies of HG or AG languages”.

Interestingly, in some regions, mobility, population size and population density were significant factors. Mobile populations and low-density populations had significantly lower borrowing rates, while smaller populations borrowed proportionately more words. This may be in line with the theory of linguistic carrying capacity as discussed by Wintz (see here and here). The level of exogamy was a significant factor in Australia.

The study concludes that phylogenetic analyses are a valid form of linguistic analysis because the level of horizontal transmission is low. That is, languages are tree-like enough for phylogenetic assumptions to be valid:

“While it is important to identify the occasional aberrant cases of high borrowing, our results support the idea that lexical evolution is largely tree-like, and justify the continued application of quantitative phylogenetic methods to examine linguistic evolution at the level of the lexicon. As is the case with biological evolution, it will be important to test the fit of trees produced by these methods to the data used to reconstruct them. However, one advantage linguists have over biologists is that they can use the methods we have described to identify borrowed lexical items and remove them from the dataset. For this reason, it has been proposed that, in cases of short to medium time depth (e.g., hundreds to several thousand years), linguistic data are superior to genetic data for reconstructing human prehistory “

Excellent – linguistics beats biology for a change!

However, while the level of horizontal transmission might not be a problem in this analysis, there may be a problem in the paths of borrowing. If a language borrows relatively few words, but those words come from many different languages, and may have many paths through previous generations, there may be a subtle effect of horizontal transition that is being masked. The authors acknowledge that they did not address the direction of transmission in a quantitative way.

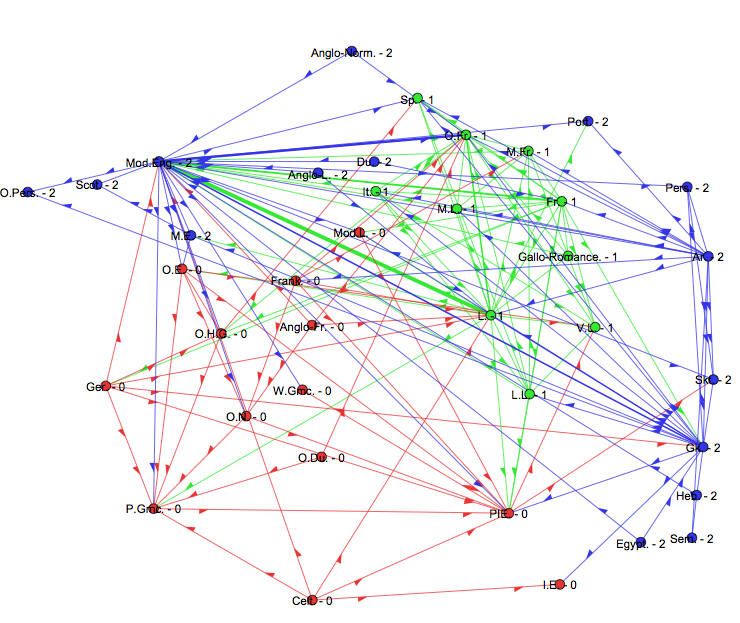

A while ago, I did study of English etymology trying to quantify the level of horizontal transmission through time (description here). The graph for English doesn’t look tree-like to me, perhaps the dynamics of borrowing works differently for languages with a high level of contact:

Claire Bowern, Patience Epps, Russell Gray, Jane Hill, Keith Hunley, Patrick McConvell, Jason Zentz (2011). Does Lateral Transmission Obscure Inheritance in Hunter-Gatherer Languages? PLoS ONE, 6 (9) : doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025195

If you want to know where people’s culture comes from, as opposed to their genes, then yes.

And did you really mean to imply that phylogenetics is not OK for biology? I’m a biological phylogeneticist and find myself rather surprised…

I admit, the title was just for hype. Phylogenetics is a cornerstone of biology and has been very productive. Although the authors are suggesting that the assumptions made by some phylogenetic analyses (e.g. no horizontal transmission) are more valid in linguistics than in biology. I’m not so sure about this – I actually think that linguistics is very confused when it comes to this kind of analysis – we haven’t really settled on a unit of inheritance in the same way as biology has settled on the gene. As it stands, we don’t really have very good data on other levels of inheritance such as syntax or phonology. Also, as I mention above, I think there is actually quite a lot of horizontal transmission.

It all depends on the data type, right? The language data they’re talking about in this paper is basic vocabulary which is more resistant to borrowing than the wider vocabulary. In English about 60% of the lexicon is borrowed from Romance languages, but only about 6% of the basic vocabulary is borrowed. Sean, your (very nice) network there is on wide English lexicon so it’ll show up much much more reticulation than the basic vocab. Russell, Dave Bryant and I talked about these issues in this paper, and show that a network of Indo-European basic vocab is surprisingly tree-like.

Oh – and re: levels of inheritance. Don’t be fooled into thinking that biologists have this sorted out. The debate about the levels of inheritance is brutal and very much on-going.

As always, you pick and choose your data to answer the question you care about. Do we care about the history of the languages (which might correspond to the history of their _cultures_)? or the history of the genes? Do we care about the population history (in which case we should look at basic vocab), or do we care about the history of contact (in which case, the wider vocab is a better source).

Simon

Your ideas about the ‘shape’ and ‘fabric’ of cultural history are really interesting. I’ll look forward to reading the article in depth.

One thing I’ve been thinking about recently is how langauge is represented in agent-based models of language evolution. Often the focus is on how individuals co-ordinate to use one of a fixed set of ‘languages’, where these languages have almost no internal structure and don’t change or develop. On the other hand, the theoretical and empirical side is more concerned with how structure emerges, but don’t focus so much on the descent of individuals. There has to be a way of representing both dynamic cultural features like langauge AND how they are distributed over individuals. A phylogenetic approach do this for real data, but I’m not sure how to import this balance into agent-based models.

Hi Sean,

A good point – I don’t know much about ABMs (it’s one of the many areas where I need to read more!), but I think there is a huge disconnect between what historical linguists do, and what sociolinguists do. Evolutionary biology has had a lot of work done linking phylogenetics (which is pretty much the analogous level of historical linguistics) and population genetics (~= the level of sociolinguistics). Unfortunately there hasn’t been too much done (that I’ve seen at least!) in linguistics.We really need some ways of investigating and working out what and how much variation happens within a language, and what and how much variation happens between languages. Two papers that go some way towards tackling this are Labov’s (2007) paper that talks about transmission and diffusion, and Malcolm Ross’s paper on the link phylogenetic/family tree structure to the outcomes of specific processes and patterns in social network break-up.

–Simon

Labov, W. 2007. Transmission and Diffusion. Language 83 (2): 344.

Ross, M. 1997. Social networks and kinds of speech-community event.â Archaeology and language I: theoretical and methodological orientations: 209.

Regarding phylogenetics in linguistics vs. biology, we need to stay with linguistics and HUMAN biology to be able to compare apples to apples. Most of the recent research seems to indicate that languages are better predictors of ethnic origin than genes. Basques are hardly different from neighboring Indo-Europeans, but linguistically they are very distinct. Same for some groups of Roma in Europe, Burushaski and Munda in India, Kets in Siberia. However, genetics is very versatile: when mtDNA phylogenies are obscured by later gene flow, Y-DNA phylogenies are a closer match with linguistics (again, Munda is good example). Hence, linguistics is more economical than genetics in answering the origins questions. Needless to say, Paleolithic linguistics is a murky territory and phylogenies haven’t been worked out beyond first-order language families. But human population genetics is equally muddled when it comes to ancient population processes, and the effects of many a layer of admixture (post 1492 European among Amerindians, Neolithic agricultural in Europe all the way down to archaic sapient admixture in Eurasia and Africa) can obfuscate genetic phylogenies beyond recovery.

I believe it’s a draw between linguistics and genetics, maybe with linguistics having an edge over genetics at least because it has a longer history of research behind it.