Here I’m just thinking out loud. I want to play around a bit.

Conrad’s Heart of Darkness is well within the 1820-1919 time span covered by Underwood and Sellers in How Quickly Do Literary Standards Change?, while Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, published in 1813, is a bit before. And both are novels, while Underwood and Sellers wrote about poetry. But these are incidental matters. My purpose is to think about literary history and the direction of cultural change, which is front and center in their inquiry. But I want to think about that topic in a hypothetical mode that is quite different from their mode of inquiry.

So, how likely is it that a book like Heart of Darkness would have been published in the second decade of the 19th century, when Pride and Prejudice was published? A lot, obviously, hangs on that word “like”. For the purposes of this post likeness means similar in the sense that Matt Jockers defined in Chapter 9 of Macroanalysis. For all I know, such a book may well have been published; if so, I’d like to see it. But I’m going to proceed on the assumption that such a book doesn’t exist.

The question I’m asking is about whether or not the literary system operates in such a way that such a book is very unlikely to have been written. If that is so, then what happened that the literary system was able to produce such a book almost a century later?

What characteristics of Heart of Darkness would have made it unlikely/impossible to publish such a book in 1813? For one thing, it involved a steamship, and steamships didn’t exist at that time. This strikes me as a superficial matter given the existence of ships of all kinds and their extensive use for transport on rivers, canals, lakes, and oceans.

Another superficial impediment is the fact that Heart is set in the Belgian Congo, but the Congo hadn’t been colonized until the last quarter of the century. European colonialism was quite extensive by that time, and much of it was quite brutal. So far as I know, the British novel in the early 19th century did not concern itself with the brutality of colonialism. Why not? Correlatively, the British novel of the time was very much interested in courtship and marriage, topics not central to Heart, but not entirely absent either.

The world is a rich and complicated affair, bursting with stories of all kinds. But some kinds of stories are more salient in a given tradition than others. What determines the salience of a given story and what drives changes in salience over time? What had happened that colonial brutality had become highly salient at the turn of the 20th century?

That’s one line of inquiry, but hardly the only one. There are also matters of literary form and technique. Though in a way it’s a minor matter, but only two of the characters in Conrad’s book are given names, Kurtz and Marlow. The others are known by phrase or title, the Intended, the Director. How would that have been received in 1813? What would readers at the time have made of a book with almost no plot to speak of, just one event after another? Marlow doesn’t seem to do anything except get a job (with the help of his aunt) and then react to the (often ghastly) circumstances of his employment. What made such a story acceptable at the beginning of the 20th century when it wasn’t acceptable early in the 19th century?

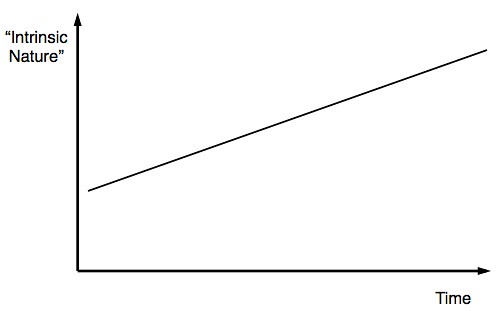

Let’s think about Macroanalysis, Chapter 9. What Jockers discovered is that novels that are published relatively close together in time resemble one another more than novels that are far apart in time. Consider this simple chart:

We have time running from left to right and we have “intrinsic nature” running from bottom top. We need to worry about just what that “intrinsic nature” is; just think of it as a crude abstract characterization of a text. Texts that are published close together in time will thus be close together along the horizontal axis. They will also be close together along the vertical axis.

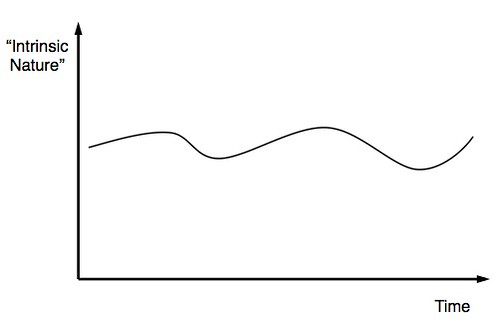

This chart is a bit different:

Here texts that are close together in time will also be close together with respect to “intrinsic nature.” But, unlike the first case, which is what Jockers found, texts that are quite distant in time may also be close together with respect to “intrinsic nature.” In this case the literary system seems to be wandering about in “literary space” while in the first case it seems to have a direction in “literary space.”

The literary system we’ve got for the 19th century seems like the first case, not the second? Why?

The system may be operating according to “historically contingent standards” (Underwood and Sellers p. 21) but those standards seem to have evolved a relatively long-term direction. Let me suggest that, in the first place, at any given time the system has quite a bit of “inertia”, if you will. I cannot make large sudden changes of direction. What we need to understand are the conditions in which the cumulative effect of relatively small changes can: 1) move from novels like Pride and Prejudice to ones like Heart of Darkness, and 2) that that turns out to be a continuous change in one direction.

I leave it as an exercise to the reader to consider the conditions under which a novel like Pride and Prejudice would have been written in the early 20th century. Is this question just like the one we’ve been thinking about, or is it quite different in character?

How is what you’re discussing different from what Jorge Luis Borges already tackled with his “Pierre Menard, autor del Quijote” in 1944? It seems to me, given the unknowables inherent in cultural studies across time, that Borges already has the advantage, since he realized that this type of undertaking was, in essence, an excursion into speculative fiction.