Wray and Grace (2007) propose that the structure of a language is dependent of the social structure of the population who speak it. Lupyan & Dale (2010) later showed this using statistical analysis. This has been discussed extensively on this blog before:

http://www.replicatedtypo.com/science/language-as-a-complex-adaptive-system/422/

One of the proposed reasons for why large population size is thought to affect linguistic structure is that larger populations will have a larger ratio of second language (L2) speakers to first language (L1) speakers.

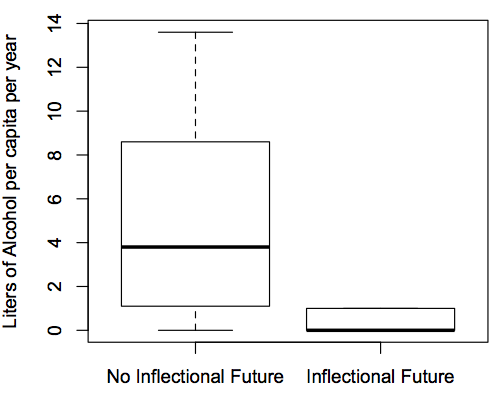

Languages within exoteric niches (large population and geographical spread with many language neighbors) have been shown to be more more morphologically isolating and, as a result, regular. This has proposed to be because of the biases of adult second language learners.

Esoteric languages are more irregular and morphologically complex and idiosyncratic. This is thought to be because of the biases of child learners.

There are studies which show that adult learners have a tendency to regularise languages but only under some circumstances. Hudson Kam & Newport (2009) show that adult learners will regularise unpredictable variability but only if it exists above a certain level of scatter and complexity.

As for the learning biases of children, Wray & Grace (2007) cite only one study which looked at children who were ‘native’ speakers of Esperanto (Bergen, 2001). Bergen (2001) found that the language that the children learnt displayed a loss of the accusative case and also displayed attrition in the tense system. Although Wray & Grace (2007) suggest that this explains patterns seen in esoteric communities, it may not be as straight forward as they suggest. The evidence suggests that esoteric conditions are going to display more morphological strategies in their languages which is the opposite to the biases the child learners of Esperanto are displaying. The children are rejecting morphological strategies in favour of attrition and word order.

I wanted to point out in this post that there is evidence to suggest that adult learners preserve irregularities and idiosyncrasies, while children learners regularize (suggesting the opposite to Wray & Grace).

Studies which have addressed these problems include Hudson Kam & Newport (2005) where adult learners of an artificial language preserved unpredictable variation and child learners of the same language regularized it. Hudson Kam & Newport (2009) show in a similar study that child learners of an artificial language will regularise unpredictable irregularity but, as mentioned above, adult learners will only do this where the irregularity passes a certain level of complexity.

However, some evidence does support Wray & Grace’s (2007) proposal about adult learners. Smith & Wonnacott (2010) show that despite there being a tendency within individual adult learners to maintain the level of unpredicted variability within the language learning process, when put into a diffusion chain of adult learners the language regularises. Smith & Wonnacott (2010) suggest that gradual processes such as this can explain the regularisation of languages over time. While this fits nicely with Wray & Grace’s (2007) theory there is still the problem that children are just as liable to regularise as adults if not more so.

This is just some relevant experiments which I thought lent something to the debate. I know there are other factors which have been proposed to have an effect on linguistic structure. I was just curious about people’s opinions on quite to what level L2 speakers have an effect.