Darwin made a mistake. At least that is what Derek Penn and his colleagues (2008) claim in a recent and controversial paper in Behavioral and Brain Sciences. Darwin (1871) famously argued that the difference between humans and animals was “one of degree, not of kind.”

This, according to Penn et al. is of course true from an evolutionary perspective, but in their view,

“the profound biological continuity between human and nonhuman animals masks an equally profound discontinuity between human and nonhuman minds” (Penn et al. 2008: 109).

They hold that humans are not simply smarter, but human cognition differs fundamentally and qualitatively from that of other animals.

One pervasive proposal is that we do not simply possess a unique set of cognitive capacities, but that it might be consciousness itself that is uniquely human as well, a view that goes back at least to Descartes (Burkhardt & Bekoff 2009: 41). However, there are also many scholars and researchers who agree that there is evidence for higher-order cognition in nonhuman animals ( ‘animals’ after this) and that they might possess at least some degree of consciousness (Burkhard & Bekoff 2009: 40f.).

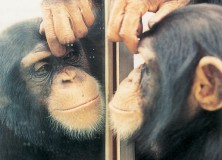

In this and my next post, I will write about three kinds of phenomena that are most often discussed in debates on whether animals have some form of higher-order cognition and consciousness or not: self-awareness, awareness of one’s own cognitive states, and awareness of others’ cognitive states and intentions.

Continue reading “Animal Cognition & Consciousness (I): Mirror Self-Recognition”