By corpus I mean a collection of texts. The texts can be of any kind, but I am interested in literature, so I’m interested in literary texts. What can we infer from a corpus of literary texts? In particular, what can we infer about history?

Well, to some extent, it depends on the corpus, no? I’m interested in an answer which is fairly general in some ways, in other ways not. The best thing to do is to pick an example and go from there.

The example I have in mind is the 3300 or so 19th century Anglophone novels that Matthew Jockers examined in Macroanalysis(2013 – so long ago, but it almost seems like yesterday). Of course, Jockers has already made plenty of inferences from that corpus. Let’s just accept them all more or less at face value. I’m after something different.

I’m thinking about the nature of historical process. Jockers’ final study, the one about influence, tells us something about that process, more than Jockers seems to realize. I think it tells us that cultural evolution is a force in human history, but I don’t intend to make that argument here. Rather, my purpose is to argue that Jockers has created evidence that can be brought to bear on that kind of assertion. The purpose of this post is to indicate why I believe that.

A direction in a 600 dimension space

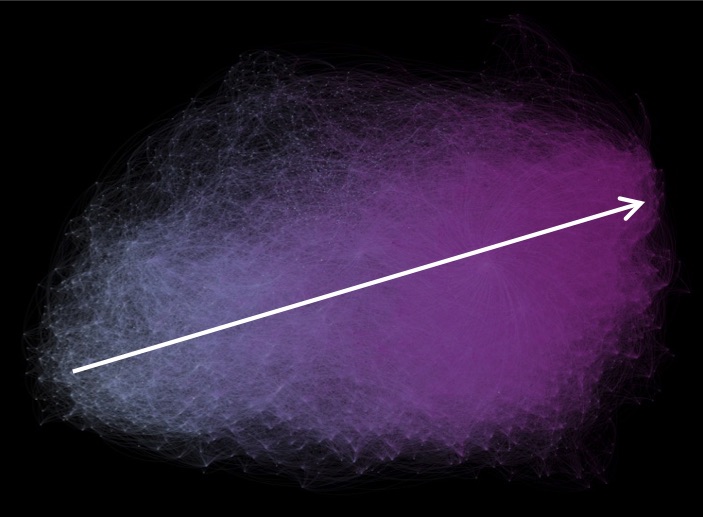

In his final study Jockers produced the following figure (I’ve superimposed the arrow):

Each node in that graph represents a single novel. The image is a 2D projection of a roughly 600 dimensional space, one dimension for each of the 600 features Jockers has identified for each novel. The length of each edge is proportional to the distance between the two nodes. Jockers has eliminated all edges above a certain relatively small value (as I recall he doesn’t tell us the cut off point). Thus two nodes are connected only if they are relatively close to one another, where Jockers takes closeness to indicate that the author of the more recent novel was influenced by the author of more distant one.

Each node in that graph represents a single novel. The image is a 2D projection of a roughly 600 dimensional space, one dimension for each of the 600 features Jockers has identified for each novel. The length of each edge is proportional to the distance between the two nodes. Jockers has eliminated all edges above a certain relatively small value (as I recall he doesn’t tell us the cut off point). Thus two nodes are connected only if they are relatively close to one another, where Jockers takes closeness to indicate that the author of the more recent novel was influenced by the author of more distant one.

You may or may not find that to be a reasonable assumption, but let’s set it aside. What interests me is the fact that the novels in this are in rough temporal order, from 1800 at the left (gray) to 1900 at the right (purple). Where did that order come from? There were no dates in 600D description of each novel. As far as I can tell, that must be a product of the historical process that produced those texts. That process must therefore have a temporal direction.

I’ve spent a fair amount of effort explicitly arguing that point [1], but don’t want to reprise that argument here. For the purposes of this piece, assume that that argument is at least a reasonable one to make.

What is that direction? I don’t have a name for it, but that’s what the arrow in the image indicates. One might call it Progress, especially with Hegel looking over your shoulder. And I admit to a bias in favor of progress, though I have no use for the notion of some ultimate telostoward which history tends. But saying that direction is progress is a gesture without substantial intellectual content because it doesn’t engage with the terms in which that 600D space is constructed. What are those terms? Some of them are topics of the sort identified in topic analysis, e.g. American slavery, beauty and affection, dreams and thoughts, Greek and Egyptian gods, knaves rogues and asses, life history, machines and industry, misery and despair, scenes of natural beauty, and so on [3]. Others are stylistic features, such as the frequency of specific words, e.g. the, heart, would, me, lady, which are the first five words in a list Jockers has in the “Style” chapter of Macroanalysis(p. 94).

In a post back in 2014 I suggested that Jockers’ image depicts the Geistof 19th century Anglo-American literary culture [2]. That’s what interests me, the possibility that we’re looking at a 21st century operationalization of an idea from 19th century German idealism. Here’s what the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy has to say about Hegel’s conception of history [4]:

In a sense Hegel’s phenomenology is a study of phenomena (although this is not a realm he would contrast with that of noumena) and Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit is likewise to be regarded as a type of propaedeutic to philosophy rather than an exercise in or work of philosophy. It is meant to function as an induction or education of the reader to the standpoint of purely conceptual thought from which philosophy can be done. As such, its structure has been compared to that of a Bildungsroman (educational novel), having an abstractly conceived protagonist—the bearer of an evolving series of so-called shapes of consciousness or the inhabitant of a series of successive phenomenal worlds—whose progress and set-backs the reader follows and learns from. Or at least this is how the work sets out: in the later sections the earlier series of shapes of consciousness becomes replaced with what seem more like configurations of human social life, and the work comes to look more like an account of interlinked forms of social existence and thought within which participants in such forms of social life conceive of themselves and the world. Hegel constructs a series of such shapes that maps onto the history of western European civilization from the Greeks to his own time.

Now, I am not proposing that Jockers’ has operationalized that conception, those “so-called shapes of consciousness”, in any way that could be used to buttress or refute Hegel’s philosophy of history – which, after all, posited a final end to history. But I am suggesting that can we reasonably interpret that image as depicting a (single) historical phenomenon, perhaps even something like an animating ‘force’, albeit one requiring a thoroughly material account. Whatever it is, it is as abstract as the Hegelian Geist.

How could that be? Continue reading “Notes toward a theory of the corpus, Part 1: History”