Imitation is often seen as one of the crucial foundations of culture because it is the basis of social learning and social transmission. Only by imitating others and learning from them did human culture become cumulative, allowing humans to build and improve on the knowledge of previous generations. Thus, it may be one of the key cognitive specializations that sparked the success of the human evolutionary story:

Much of the success of our species rests on our ability to learn from others’ actions. From the simplest preverbal communication to the most complex adult expertise, a remarkable proportion of our abilities are learned by imitating those around us. Imitation is a critical part of what makes us cognitively human and generally constitutes a significant advantage over our primate relatives (Lyons et al. 2007: 19751).

Indeed, there have been some interesting experiments suggesting that the human capacity -and, above all, motivation – for imitation is an important characteristic that separates us from the other great apes.

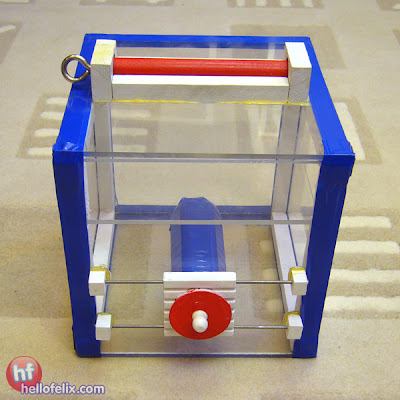

In a series of intriguing experiments by Victoria Horner and Andrew Whiten from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, and Derek Lyons and his colleagues from Yale University, young wild-born chimpanzees and Children aged 3 to 4 were shown how to get a little toy turtle/ a reward out of a puzzle box. In the first condition of the experiment the puzzle box was transparent, whereas in the second condition the puzzle box was opaque.

And here’s the catch: both chimpanzees and children were not shown the ‘right’ or ‘simple’ solution to how to get the reward but one that was actually more complicated and involved unnecessary steps.