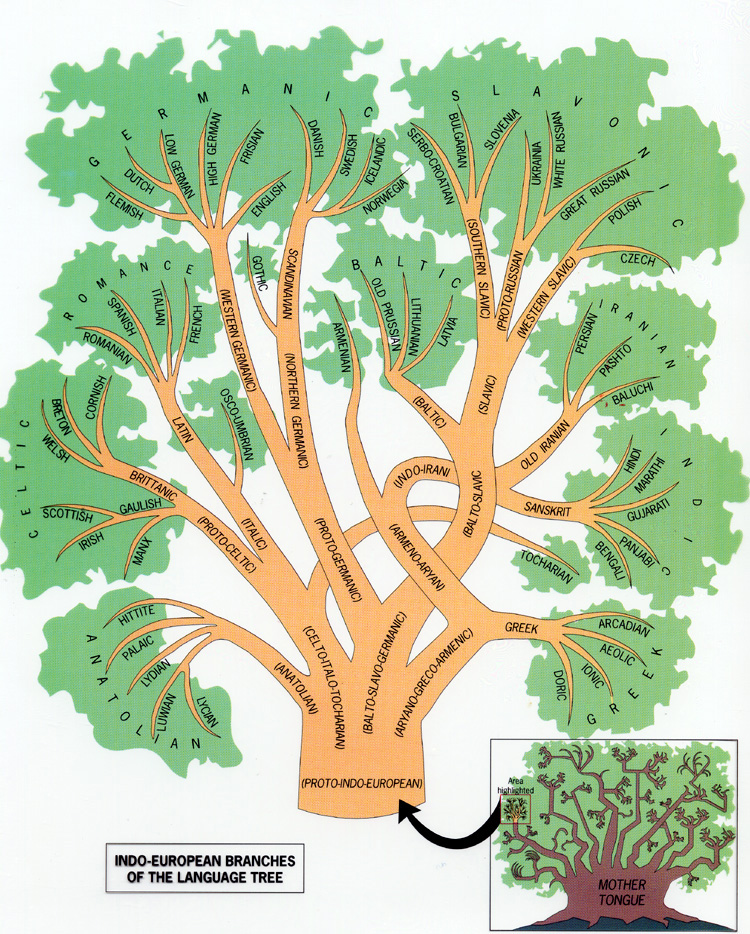

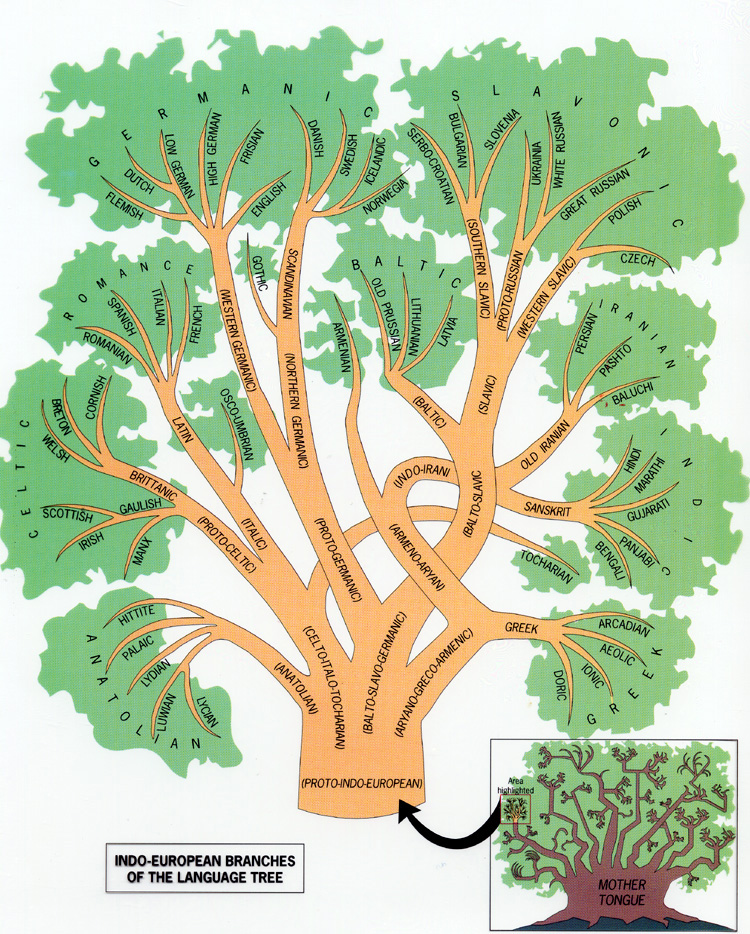

A recent post by Miko on Kirschner and Gerhart’s work on developmental constraints and the implications for evolutionary biology caught my eye due to the possible analogues which could be drawn with language in mind. It starts by saying that developmental constraints are the most intuitive out of all of the known constraints on phenotypic variation. Essentially, whatever evolves must evolve from the starting point, and it cannot ignore the features of the original. Thus, a winged horse would not occur, as six limbs would violate the basic bauplan of tetrapods. In the same way, a daughter language cannot evolve without taking into account the language it derives from and language universals. But instead of viewing this as a constraint which limits the massive variation we see biologically or linguistically between different phenotypes, developmental constraints can be seen as a catalyst for regular variation.

A recent post by Miko on Kirschner and Gerhart’s work on developmental constraints and the implications for evolutionary biology caught my eye due to the possible analogues which could be drawn with language in mind. It starts by saying that developmental constraints are the most intuitive out of all of the known constraints on phenotypic variation. Essentially, whatever evolves must evolve from the starting point, and it cannot ignore the features of the original. Thus, a winged horse would not occur, as six limbs would violate the basic bauplan of tetrapods. In the same way, a daughter language cannot evolve without taking into account the language it derives from and language universals. But instead of viewing this as a constraint which limits the massive variation we see biologically or linguistically between different phenotypes, developmental constraints can be seen as a catalyst for regular variation.

A recent post by Miko on Kirschner and Gerhart’s work on developmental constraints and the implications for evolutionary biology caught my eye due to the possible analogues which could be drawn with language in mind. It starts by saying that developmental constraints are the most intuitive out of all of the known constraints on phenotypic variation. Essentially, whatever evolves must evolve from the starting point, and it cannot ignore the features of the original. Thus, a winged horse would not occur, as six limbs would violate the basic bauplan of tetrapods. In the same way, a daughter language cannot evolve without taking into account the language it derives from and language universals. But instead of viewing this as a constraint which limits the massive variation we see biologically or linguistically between different phenotypes, developmental constraints can be seen as a catalyst for regular variation.

A pretty and random tree showing variation among IE languages.

Looking back over my courses, I’m surprised by how little I’ve noticed (different from how much was actually said) about reasons for linguistic variation. The modes of change are often noted: <th> is fronted in Fife, for instance, leading to the ‘Firsty Ferret’ instead of the ‘Thirsty Ferret’ as a brew, for instance. However, why the <th> is fronted at all isn’t explained beyond cursory hypothesis. But that’s a bit besides the point: what is the point is that phenotypic variation is not necessarily random, as there are constraints – due to the “buffering and canalizing of development” – which limit variation to a defined range of possibilities. There clearly aren’t any homologues between biological embryonic processes and linguistic constraints, but there are developmental analogues: the input bottleneck (paucity of data) given to children, learnability constraints, the necessity for communication, certain biological constraints to do with production and perception, etc. These all act on language to make variation occur only within certain channels, many of which would be predictable.

Another interesting point raised by the article is the robustness of living systems to mutation. The buffering effect of embryonic development results in the accumulation of ‘silent’ variation. This has been termed evolutionary capacitance. Silent variation can lay quiet, accumulating, not changing the phenotype noticeably until environmental or genetic conditions unmask them. I’ve seen little research (not that I don’t expect there to be plenty) on the theoretical implications of the influence of evolutionary capacitance on language change – in other words, how likely a language is to make small variations which don’t affect language understanding before a new language emerges (not that the term language isn’t arbitrary based on the speaking community, anyway). Are some languages more robust than others? Is robustness a quality which makes a language more likely to be used in multilingual settings – for instance, in New Guinea, if seven languages are mutually indistinguishable, is it likely the that local lingua franca is forced by its environment to be more robust in order to maximise comprehension?

The article goes on about the cost of robustness: stasis. This can be seen clearly in Late Latin, which was more robust than the daughter languages as it was needed to communicate in different environments where the language had branched off into the Romance languages, and an older form was necessary in order for communication to ensue. Thus, Latin retained usage well after the rest of it had evolved into other languages. Another example would be Homeric Greek, which retained many features lost in Attic, Doric, Koine, and other dialects, as it was used in only a certain environment and was therefore resistant to change. This has all been studied before better than I can sum it up here. But the point I am making is that analogues can be clearly drawn here, and some interesting theories regarding language become apparent only when seen in this light.

A good example, also covered, would be exploratory processes, as Kirschner and Gerhart call them. These are processes which allow for variation to occur in environments where other variables are forced to change. The example given is the growth of bone length, which requires corresponding muscular, circulatory, and other dependant systems to also change. The exploratory processes allow for future change to occur in the other systems. That is, they expedite plasticity. So, for instance, an ad hoc linguistic example would be the loss of a fixed word order, which would require that morphology step in to fill the gap. In such a case, particles or affixes or the like would have to have already paved the way for case markers to evolve, and would have had to have been present to some extent in the original word order system. (This may not be the best example, but I hope my point comes across.)

Naturally, much of this will have seemed intuitive. But, as Miko stated, these are useful concepts for thinking about evolution; and, in my own case especially, the basics ought to be brought back into scrutiny fairly frequently. Which is justification enough for this post. As always, comments appreciated and accepted. And a possible future post: clade selection as a nonsensical way to approach phylogenic variation.

References:

Caldwell, M. (2002). From fins to limbs to fins: Limb evolution in fossil marine reptiles American Journal of Medical Genetics, 112 (3), 236-249 DOI: 10.1002/ajmg.10773

Gerhart, J., & Kirschner, M. (2007). Colloquium Papers: The theory of facilitated variation Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (suppl_1), 8582-8589 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0701035104

Gerhart, J., & Kirschner, M. (2007). Colloquium Papers: The theory of facilitated variation Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 104 (suppl_1), 8582-8589 DOI: 10.1073/pnas.0701035104

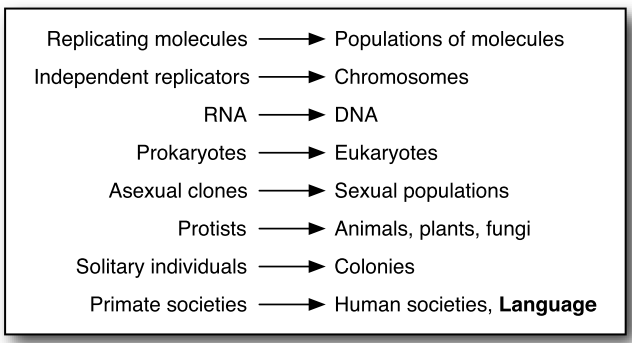

![]() Just before Christmas I found myself in the pub speaking to Sean about his work on bilingualism, major transitions and the contrast between language change and the cultural evolution of language. Now, other than revealing that our social time is spent discussing our university work, the conversation brought up a distinction not often made: whilst language change is part of language evolution, the latter is also what we consider to be a major transition. As you evolutionary biologists will know, this concept is perhaps best examined and almost certainly popularised in Maynard Smith & Szathmáry’s (1995) The Major Transitions in Evolution. Here, the authors are not promoting the fallacy of guided evolution, where the inevitable consequence is increased and universal complexity. Their thesis is more subtle: that some lineages become more complex over time, with this increase being attributable to the way in which genetic information is transmitted between generations. In particular, they note eight transitions in the evolution of life:

Just before Christmas I found myself in the pub speaking to Sean about his work on bilingualism, major transitions and the contrast between language change and the cultural evolution of language. Now, other than revealing that our social time is spent discussing our university work, the conversation brought up a distinction not often made: whilst language change is part of language evolution, the latter is also what we consider to be a major transition. As you evolutionary biologists will know, this concept is perhaps best examined and almost certainly popularised in Maynard Smith & Szathmáry’s (1995) The Major Transitions in Evolution. Here, the authors are not promoting the fallacy of guided evolution, where the inevitable consequence is increased and universal complexity. Their thesis is more subtle: that some lineages become more complex over time, with this increase being attributable to the way in which genetic information is transmitted between generations. In particular, they note eight transitions in the evolution of life: What’s notable about these transitions, and why they aren’t necessarily an arbitrary list, is that all of them share some broad commonalities, namely:

What’s notable about these transitions, and why they aren’t necessarily an arbitrary list, is that all of them share some broad commonalities, namely: