“a post on Pinker and Bloom’s original paper, and how the field has developed over these last twenty years, at some point in the next couple of weeks,”

Tag: adaptation

Some Links #6: We are all Keynesians now. Yeah, but which type?

If you think economic cuts are necessary, you’re being fooled. Martyn Winters (known to me as dad) writes about Joseph Stiglitz’s thoughts on George Osborne’s attempts to reduce the deficit:

You may have heard of Professor Joseph Stiglitz – he’s the Nobel laureate economist who correctly predicted the global crash. He’s distinctly unimpressed with Osbourne’s budget. This, he predicts, will make Britain’s recovery from recession longer, slower and harder than it needs to be. The rise in VAT could even tip us into a double-dip recession. He took time to offer George Osbourne a bit of advice – which will probably go unheeded, because Osbourne’s objectives aren’t necessarily to improve the economy. They are an ideological attack on the state, with the intention of shrinking it by forty percent.

The basis for this is part Keynesian, and has been echoed by other commentators such as Johann Hari, in that we must spend our way out of economic woes. Now I must admit I’m not too fond of how Osborne is going about reducing deficit (raising VAT… huh?), but, for reasons that’ll become apparent below, I do think we need to tackle the deficit.

Continue reading “Some Links #6: We are all Keynesians now. Yeah, but which type?”

Population size predicts technological complexity in Oceania

![]() Here is a far-reaching and crucially relevant question for those of us seeking to understand the evolution of culture: Is there any relationship between population size and tool kit diversity or complexity? This question is important because, if met with an affirmative answer, then the emergence of modern human culture may be explained by changes in population size, rather than a species-wide cognitive explosion. Some attempts at an answer have led to models which make certain predictions about what we expect to see when populations vary. For instance, Shennan (2001) argues that in smaller populations, the number of people adopting a particular cultural variant is more likely to be affected by sampling variation. So in larger populations, learners potentially have access to a greater number of experts, which means adaptive variants are less likely to be lost by chance (Henrich, 2004).

Here is a far-reaching and crucially relevant question for those of us seeking to understand the evolution of culture: Is there any relationship between population size and tool kit diversity or complexity? This question is important because, if met with an affirmative answer, then the emergence of modern human culture may be explained by changes in population size, rather than a species-wide cognitive explosion. Some attempts at an answer have led to models which make certain predictions about what we expect to see when populations vary. For instance, Shennan (2001) argues that in smaller populations, the number of people adopting a particular cultural variant is more likely to be affected by sampling variation. So in larger populations, learners potentially have access to a greater number of experts, which means adaptive variants are less likely to be lost by chance (Henrich, 2004).

Models aside, and existing empirical evidence is limited with the results being mixed. I previously mentioned the gradual loss of complexity in Tasmanian tool kits after the population was isolated from mainland Australia. Elsewhere, Golden (2006) highlighted the case of isolated Polar Inuit, who lost kayaks, the bow and arrow and other technologies when their knowledgeable experts were wiped out during a plague.Yet two systematic studies (Collard et al., 2005; Read, 2008) of the Inuit case found no evidence for population size being a predictor of technological complexity.

Continue reading “Population size predicts technological complexity in Oceania”

Answering Wallace's challenge: Relaxed Selection and Language Evolution

![]() How does natural selection account for language? Darwin wrestled with it, Chomsky sidestepped it, and Pinker claimed to solve it. Discerning the evolution of language is therefore a much sought endeavour, with a vast number of explanations emerging that offer a plethora of choice, but little in the way of consensus. This is hardly new, and at times has seemed completely frivolous and trivial. So much so that in the 19th Century, the Royal Linguistic Society in London actually went as far as to ban any discussion and debate on the origins of language. Put simply: we don’t really know that much. Often quoted in these debates is Alfred Russell Wallace, who, in a letter to Darwin, argued that: “natural selection could only have endowed the savage with a brain a little superior to that of an ape whereas he possesses one very little inferior to that of an average member of our learned society”.

How does natural selection account for language? Darwin wrestled with it, Chomsky sidestepped it, and Pinker claimed to solve it. Discerning the evolution of language is therefore a much sought endeavour, with a vast number of explanations emerging that offer a plethora of choice, but little in the way of consensus. This is hardly new, and at times has seemed completely frivolous and trivial. So much so that in the 19th Century, the Royal Linguistic Society in London actually went as far as to ban any discussion and debate on the origins of language. Put simply: we don’t really know that much. Often quoted in these debates is Alfred Russell Wallace, who, in a letter to Darwin, argued that: “natural selection could only have endowed the savage with a brain a little superior to that of an ape whereas he possesses one very little inferior to that of an average member of our learned society”.

This is obviously relevant for those of us studying language evolution. If, as Wallace challenged, natural selection (and more broadly, evolution) is unable to account for our mental capacities and behavioural capabilities, then what is the source behind our propensity for language? Well, I think we’ve come far enough to rule out the spiritual explanations of Wallace (although it still persists on some corners of the web), and whilst I agree that biological natural selection alone is not sufficient to explain language, we can certainly place it in an evolutionary framework.

Such is the position of Prof Terrence Deacon, who, in his current paper for PNAS, eloquently argues for a role for relaxed selection in the evolution of the language capacity. He’s been making these noises for a while now, as I previously mentioned here, with him also recognising evolutionary-similar processes in development. However, with the publication of this paper I think it’s about time I disseminated his current ideas in more detail, which, in my humble opinion, offers a more nuanced position than the strict modular adaptationism previously championed by Pinker et al (I say previously, because Pinker also has a paper in this issue, and I’m going to read it before making any claims about his current position on the matter).

Continue reading “Answering Wallace's challenge: Relaxed Selection and Language Evolution”

Some links #3

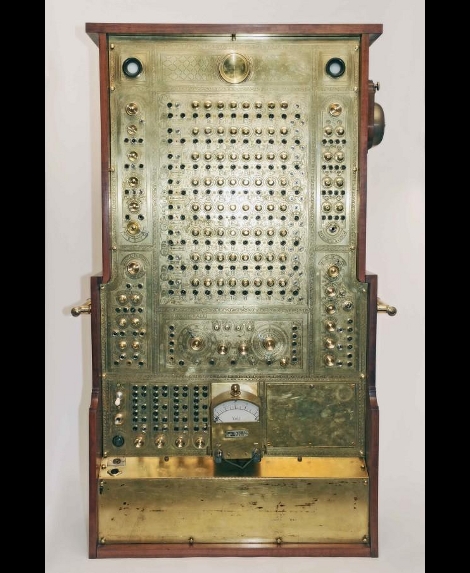

Of my random meanderings around the Internet, I think the coolest thing I’ve seen this past week certainly has to be the Steampunk sequencer:

With that out of the way, here are some links:

- In somewhat keeping with the theme from some links 2’s look at primitive writing systems, comes a post from the excellent Not Exactly Rocket Science: An 60,000-year old artistic movement recorded in Ostrich egg shells.

- More on topic of writing systems is Kevin Mitchell’s post on Why Johnny can’t read (but Jane can). Essentially, the post is asking: why dyslexia is about twice as common in boys as in girls?

- Is synaesthesia a high-level brain power? I’m not sure, but that’s the question being asked over at New Scientist.

- Science Daily claims: Simple math explains dramatic beak shape variation in Darwin’s finches. Key paragraph: “Using digitization techniques, the researchers found that 14 distinct beak shapes, that at first glance look unrelated, could be categorized into three broader, group shapes. Despite the striking variety of sizes and shapes, mathematically, the beaks within a particular group only differ by their scales.”

- Pamelia Brown has 50 Fascinating Lectures All About Your Brain. I’ve only managed to watch one of the videos (see below), so I’m certain that there is at least one fascinating lecture…

- Be sure to check out the Kahn Academy — a not-for-profit organisation that provides some great educational resources. For those of you interested in demographics and the quantitative analysis of movement, then here’s a whole section on differential equations.

- Dormivigilia provides a brief overview of a paper examining the neural origins of handedness.

- Razib Kahn over at GNXP has an in-depth discussion about the convergent evolution of skin pigmentation: OCA2 makes East Asians white and Europeans blue.

- How reliable are fMRI results? Another question I’m not so sure about. However, Prefrontal.org has a full paper on providing something of an answer. The key sentence: “the results from fMRI research may be somewhat less reliable than many researchers implicitly believe.”

- Jonah Leher has a lengthy, interesting piece over at the New York Times, asking: Is depression an adaptation? Probably not. But for a more balanced perspective, read Neurocritic’s brilliant analysis of the topic.

- Laelaps writes about a paper claiming the discovery a 4,300 year old chimpanzee nut-cracking site: Uncovering the “Chimpanzee Stone Age”.

- Lastly, Jeff Elman, UCSD professor of cognitive science and co-director of the Kavli Institute for Brain and Mind, presents a lecture on some of the latest research in our ability to use language and why it is so far removed from other animal communication systems:

Some Links #2

This week we all get to learn a new word, the potential origins of the written word and killing at a distance. Enjoy!

- Archaeogenetics — yet another call for multi-discipline research? Yes, and the latest issue of Current Biology has a load of free (yes, free) papers on archaeogenetics. I haven’t had chance to read all of them, but it’s certainly worth checking out these two: Archaeogenetics — towards a ‘New Synthesis’? and The Genetics of Human Adaptation: Hard Sweeps, Soft Sweeps, and Polygenic Adaptation.

- New Scientist discusses research into the discovery of primitive writing systems from 35,000 years ago. Obviously, this has massive implications for those of us who thought the seeds of writing were only starting to emerge approximately 5000-years-ago. The key paragraph: “What emerged was startling: 26 signs, all drawn in the same style, appeared again and again at numerous sites (see illustration). Admittedly, some of the symbols are pretty basic, like straight lines, circles and triangles, but the fact that many of the more complex designs also appeared in several places hinted to von Petzinger and Nowell that they were meaningful – perhaps even the seeds of written communication.” They’ve also got some pretty pictures.

- If you’re looking for good news regarding the economy, then don’t go over to Washington’s Blog. He has a short post on Alan Greenspan’s assertion that we’re in the worst financial crisis ever.

- I’ve been reading a lot of articles over at the brilliant blog, Emergent Fool. Of particular interest are posts relating to my recent article on cumulative culture and coordinated behaviour: Rafe Furst discusses three types of cooperation, cultural agency and complex systems concept summary. Meanwhile, Plektix writes about how human cultural transformation was triggered by dense populations.

- Emergent Fool also led me to an in-depth essay by Professor Yaneer Bar-Yam on emergence and complexity: complexity rising: from human beings to human civilization, a complexity profile.

- Lastly, American Scientist has a podcast on the evolution of the human capacity for killing at a distance. Here’s the summary: “Duke University anthropologist Steven Churchill presents his research on the evolutionary origins of projectile weaponry, and how weapon use changed interactions between humans and other species—including, perhaps, the Neandertals.”

How do biology and culture interact?

In the year of Darwin, I’m not too surprised at the number of articles being published on the interactions between cultural change and biological evolution — this synthesis, if achieved, will certainly be a crucial step in explaining how humans evolved. Still, it’s unlikely we’re going to see the Darwin of culture in 2009, given we’re still disputing some of the fundamentals surrounding these two modes of evolution. One of these key arguments is whether or not culture inhibits biological evolution. That we’re seeing accelerated changes in the human genome seems to suggest (for some) that culture is one of these evolutionary selection pressures, as John Hawks explains:

Continue reading “How do biology and culture interact?”

Current Issues in Language Evolution

As part of my assessment this term I’m to write four mock peer-reviewed items for a module called Current Issues in Language Evolution. It’s a great module run by Simon Kirby, examining some of the best food for thought in the field. Alone this is an interesting endeavour, after all we’re right in the middle of a language evolution renaissance, however, even cooler are the lectures, where students get to do their own presentations on a particular paper. I already did my presentation at the start of this term, on Dediu and Ladd’s paper, which went rather well, even if one of my slip ups did not go unnoticed (hint: always label the graphs). So, over the next few weeks, in amongst additional posts covering some of the presentations in class, I’ll hopefully be writing articles on these four five papers:

Schizophrenia and brain evolution (plus bold adjectives)

![]() When exploring the etiology of schizophrenia, a feat that has mostly eluded understanding for over 100 years, a common denominator emerges in that associated deficiencies are rooted in cognitively demanding tasks. One suggestion is that, where schizophrenic individuals are involved, disorganised thoughts, abnormal speech, auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions are symptomatic consequences of our haphazardly evolved brains. It might not seem revelatory, nor is it a particularly new thought on the matter, yet this disorder clearly has ties with human-specific, recently evolved behaviours, such as language and social relationships. And it is here in which our problem emerges: we don’t even know how language or social relationships evolved. In fact, the evolution of the human brain is still very much an enigma, despite the whole host of literature having you believe otherwise. As Darwin put it: “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge[…]”.

When exploring the etiology of schizophrenia, a feat that has mostly eluded understanding for over 100 years, a common denominator emerges in that associated deficiencies are rooted in cognitively demanding tasks. One suggestion is that, where schizophrenic individuals are involved, disorganised thoughts, abnormal speech, auditory hallucinations and paranoid delusions are symptomatic consequences of our haphazardly evolved brains. It might not seem revelatory, nor is it a particularly new thought on the matter, yet this disorder clearly has ties with human-specific, recently evolved behaviours, such as language and social relationships. And it is here in which our problem emerges: we don’t even know how language or social relationships evolved. In fact, the evolution of the human brain is still very much an enigma, despite the whole host of literature having you believe otherwise. As Darwin put it: “Ignorance more frequently begets confidence than does knowledge[…]”.

Continue reading “Schizophrenia and brain evolution (plus bold adjectives)”