In thinking about the recent LARB critique of digital humanities and of responses to it I couldn’t help but think, once again, about the term itself: “digital humanities.” One criticism is simply that Allington, Brouillette, and Golumbia (ABG) had a circumscribed conception of DH that left too much out of account. But then the term has such a diverse range of reference that discussing DH in a way that is both coherent and compact is all but impossible. Moreover, that diffuseness has led some people in the field to distance themselves from the term.

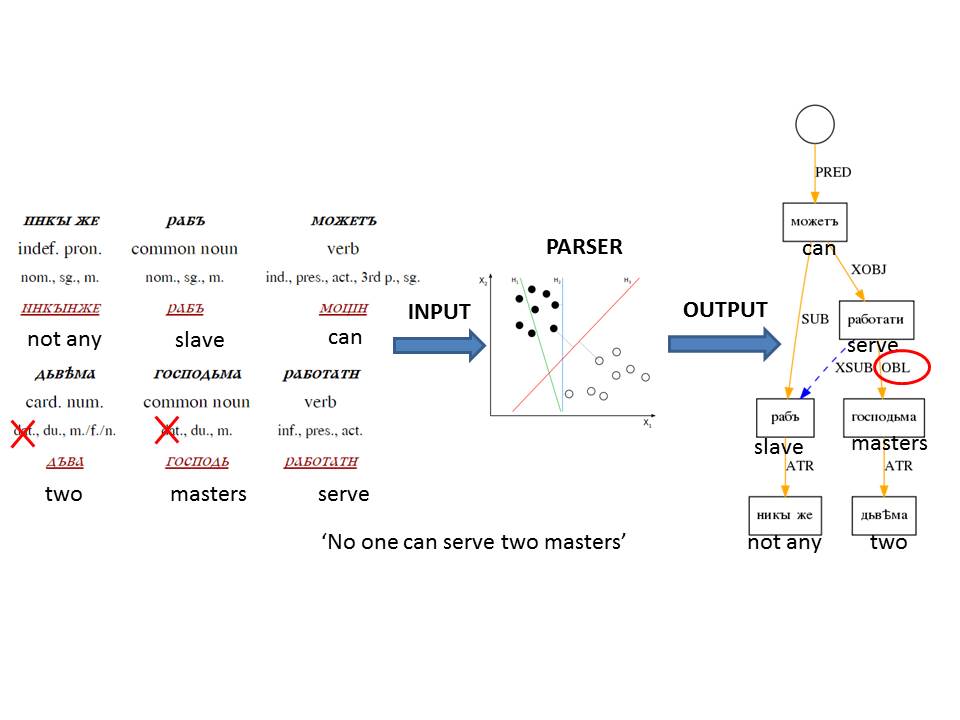

And so I found my way to some articles that Matthew Kirschenbaum has written more or less about the term itself. But I also found myself thinking about another term, one considerably older: “computational linguistics.” While it has not been problematic in the way DH is proving to be, it was coined under the pressure of practical circumstances and the discipline it names has changed out from under it. Both terms, of course, must grapple with the complex intrusion of computing machines into our life ways.

Digital Humanities

Let’s begin with Kirschenbaum’s “Digital Humanities as/Is a Tactical Term” from Debates in the Digital Humanities (2011):

To assert that digital humanities is a “tactical” coinage is not simply to indulge in neopragmatic relativism. Rather, it is to insist on the reality of circumstances in which it is unabashedly deployed to get things done—“things” that might include getting a faculty line or funding a staff position, establishing a curriculum, revamping a lab, or launching a center. At a moment when the academy in general and the humanities in particular are the objects of massive and wrenching changes, digital humanities emerges as a rare vector for jujitsu, simultaneously serving to position the humanities at the very forefront of certain value-laden agendas—entrepreneurship, openness and public engagement, future-oriented thinking, collaboration, interdisciplinarity, big data, industry tie-ins, and distance or distributed education—while at the same time allowing for various forms of intrainstitutional mobility as new courses are approved, new colleagues are hired, new resources are allotted, and old resources are reallocated.

Just so, the way of the world.

Kirschenbaum then goes into the weeds of discussions that took place at the University of Virginia while a bunch of scholars where trying to form a discipline. So:

A tactically aware reading of the foregoing would note that tension had clearly centered on the gerund “computing” and its service connotations (and we might note that a verb functioning as a noun occupies a service posture even as a part of speech). “Media,” as a proper noun, enters the deliberations of the group already backed by the disciplinary machinery of “media studies” (also the name of the then new program at Virginia in which the curriculum would eventually be housed) and thus seems to offer a safer landing place. In addition, there is the implicit shift in emphasis from computing as numeric calculation to media and the representational spaces they inhabit—a move also compatible with the introduction of “knowledge representation” into the terms under discussion.

How we then get from “digital media” to “digital humanities” is an open question. There is no discussion of the lexical shift in the materials available online for the 2001–2 seminar, which is simply titled, ex cathedra, “Digital Humanities Curriculum Seminar.” The key substitution—“humanities” for “media”—seems straightforward enough, on the one hand serving to topically define the scope of the endeavor while also producing a novel construction to rescue it from the flats of the generic phrase “digital media.” And it preserves, by chiasmus, one half of the former appellation, though “humanities” is now simply a noun modified by an adjective.

And there we have it. Continue reading “What’s in a Name? – “Digital Humanities” [#DH] and “Computational Linguistics””

![What’s in a Name? – “Digital Humanities” [#DH] and “Computational Linguistics”](http://www.replicatedtypo.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/20160514-_IGP6641-e1464037525388-672x372.jpg)