An article in PLos ONE debunks the myth that hunter-gatherer societies borrow more words than agriculturalist societies. In doing so, it suggests that horizontal transmission is low enough for phylogenetic analyses to be a valid linguistic tool.

Lexicons from around 20% of the extant languages spoken by hunter-gatherer societies were coded for etymology (available in the supplementary material). The levels of borrowed words were compared with the languages of agriculturalist and urban societies taken from the World Loanword Database. The study focussed on three locations: Northern Australia, northwest Amazonia, and California and the Great Basin.

In opposition to some previous hypotheses, hunter-gatherer societies did not borrow significantly more words than agricultural societies in any of the regions studied.

The rates of borrowing were universally low, with most languages not borrowing more than 10% of their basic vocabulary. The mean rate for hunter-gatherer societies was 6.38% while the mean for 5.15%. This difference is actually significant overall, but not within particular regions. Therefore, the authors claim, “individual area variation is more important than any general tendencies of HG or AG languages”.

Interestingly, in some regions, mobility, population size and population density were significant factors. Mobile populations and low-density populations had significantly lower borrowing rates, while smaller populations borrowed proportionately more words. This may be in line with the theory of linguistic carrying capacity as discussed by Wintz (see here and here). The level of exogamy was a significant factor in Australia.

The study concludes that phylogenetic analyses are a valid form of linguistic analysis because the level of horizontal transmission is low. That is, languages are tree-like enough for phylogenetic assumptions to be valid:

“While it is important to identify the occasional aberrant cases of high borrowing, our results support the idea that lexical evolution is largely tree-like, and justify the continued application of quantitative phylogenetic methods to examine linguistic evolution at the level of the lexicon. As is the case with biological evolution, it will be important to test the fit of trees produced by these methods to the data used to reconstruct them. However, one advantage linguists have over biologists is that they can use the methods we have described to identify borrowed lexical items and remove them from the dataset. For this reason, it has been proposed that, in cases of short to medium time depth (e.g., hundreds to several thousand years), linguistic data are superior to genetic data for reconstructing human prehistory “

Excellent – linguistics beats biology for a change!

However, while the level of horizontal transmission might not be a problem in this analysis, there may be a problem in the paths of borrowing. If a language borrows relatively few words, but those words come from many different languages, and may have many paths through previous generations, there may be a subtle effect of horizontal transition that is being masked. The authors acknowledge that they did not address the direction of transmission in a quantitative way.

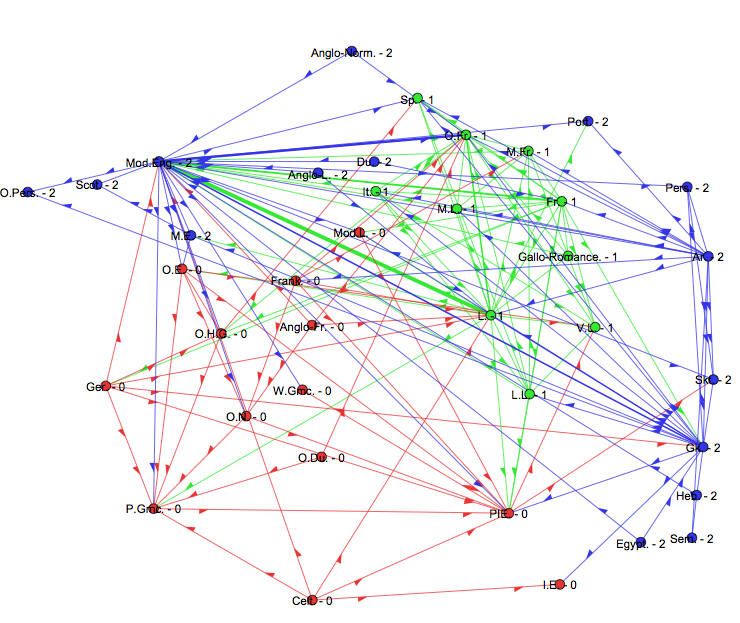

A while ago, I did study of English etymology trying to quantify the level of horizontal transmission through time (description here). The graph for English doesn’t look tree-like to me, perhaps the dynamics of borrowing works differently for languages with a high level of contact:

Claire Bowern, Patience Epps, Russell Gray, Jane Hill, Keith Hunley, Patrick McConvell, Jason Zentz (2011). Does Lateral Transmission Obscure Inheritance in Hunter-Gatherer Languages? PLoS ONE, 6 (9) : doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025195