Discussing the concept of recursion is like a rite of passage for anyone interested in language evolution: you go through it once, take a position and hope it doesn’t come back to haunt you. As Hannah pointed out last year, there are two definitions of recursion:

(1) embeddedness of phrases within other phrases, which entails keeping track of long-distance dependencies among phrases;

(2) the specification of the computed output string itself, including meta-recursion, where recursion is both the recipe for an utterance and the overarching process that creates and executes the recipe.

The case of grammatical recursion (see definition 1) is perhaps most famously associated with Noam Chomsky. Not only does he claim all human languages are recursive, but also that this ability is biologically hardwired as part of our genetic makeup. Countering Chomsky’s first claim is the debate surrounding a small Amazonian tribe called the Pirahã: even though they show signs of recursion, such as the ability to recursively embed structures within stories, the Pirahã grammar is claimed not to recursively embed phrases within other phrases. If true, then are numerous implications for a wide variety of fields in linguistics, but this is still an unsubstantiated claim: for the most part, we are relying on one specific researcher (Daniel Everett) who, despite having dedicated a large portion of his life to studying the tribe, could very well have been misled. That said, I retain a large amount of respect for Everett, having watched him speak at Edinburgh a few years ago and read his book on the topic: Don’t Sleep, There are Snakes: Life and Language in the Amazonian Jungle.

So, why am I rambling on about recursion? Well, besides its obvious relevance, — and perhaps under-representation on this blog (deserved or not, I’ll let you decide) — Everrett has recently published a series of slides about a corpus study of Pirahã grammar (see below).

[gview file=”http://tedlab.mit.edu/tedlab_website/researchpapers/piantadosi_et_al_piraha_lsa_2012.pdf”]

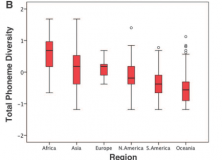

His tentative conclusion: there is no strong evidence for recursion among relative clauses, complement clauses, possessive structures and conjunctions/disjunctions. However, there is possible evidence of recursive structure in topics/repeated arguments. He also posits cultural pressures for longer or shorter sentences, such as writing systems (as I mentioned way back in 2009).

I’m sure this debate will be brought to the fore at this year’s EvoLang, with Chomsky Berwick Piattelli-Palmarini and many of the Biolinguistic crowd in attendance, and it’s a shame I’ll almost certainly miss it (unless someone wants to pay for my ticket… Just hit the donate button in the left-hand corner 😉 ).

Continue reading “Everett, Pirahã and Recursion: The Latest”