Evolang is busy this year – 4 parallel sessions and over 50 posters. We’ll be positing a series of previews to help you decide what to go and see. If you’d like to post a preview of your work, get in touch and we’ll give you a guest slot.

Richard Littauer The Evolution of Morphological Agreement

Every lecture theatre but Lecture Theatre 1, all times except 14:45-15:05, and certainly not on Friday 16th

In this talk I’m basically outlining the debate as I see it about the evolution of morphology, focusing on agreement as a syntactic phenomenon. There are three main camps: Heine and Kuteva forward grammaticalisation, and say that agreement comes last in the process, and therefore probably last in evolution; Hurford basically states that agreement is part of semantic neural mapping in the brain, and evolved at the same time as protomorphology and protosyntax; and then there’s another, larger camp who basically view agreement as the detritus of complex language. I agree with Hurford, and I propose in this paper that it had to be there earlier, as, quite simply put, there is too much evidence for the use of agreement than for its lack. Unfortunately, I don’t have any empirical or experimental results or studies – this is all purely theoretical – and so this is both a work in progress and a call to arms. Which is to say: theoretical.

First, I define agreement and explain that I’m using Corbett’s (who wrote the book Agreement) terms. This becomes relevant up later. Then I go on to cite Carstairs-McCarthy, saying that basically there’s no point looking at a single language’s agreement for functions, as it is such varied functions. It is best to look at all languages. So, I go on to talk about various functions: pro-drop, redundancy, as an aid in parsing, and syntactic marking, etc.

Carstairs-McCarthy is also important for my talk in that he states that historical analyses of agreement can only go so far, because grammaticalisation basically means that we have to show the roots of agreement in modern languages in the phonology and syntax, as this is where they culturally evolve from in today’s languages. I agree with this – and I also think that basically this means that we can’t use modern diachronic analyses to look at proto-agreement. I think this is the case mainly due to Lupyan and Dale, and other such researchers like Wray, who talk about esoteric and exoteric languages. Essentially, smaller communities tend to have larger morphological inventories. Why is this the case? Because they don’t have as many second language learners, for one, and there’s less dialectical variation. I think that today we’ve crossed a kind of Fosbury Flop in languages that are too large, and I think that this is shown in the theories of syntacticians, who tend to delegate morphology wherever it can’t bother their theories. I’m aware I’m using a lot of ‘I think’ statements – in the talk, I’ll do my best to back these up with actual research.

Now, why is it that morphology, and in particular agreement morphology, which is incredibly redundant and helpful for learners, is pushed back after syntax? Well, part of the reason is that pidgins and creoles don’t really have any. I argue that this doesn’t reflect early languages, which always had an n-1 generation (I’m a creeper, not a jerk*), as opposed to pidgins. I also quote some child studies which show that kids can pick up morphology just as fast as syntax, nullifying that argument. There’s also a pathological case that supports my position on this.

Going back to Corbett, I try to show that canonical agreement – the clearest cases, but not necessarily the most distributed cases – would be helpful on all counts for the hearer. I’d really like to back this up with empirical studies, and perhaps in the future I’ll be able to. I got through some of the key points of Corbett’s hierarchy, and even give my one morphological trilinear gloss example (I’m short on time, and remember, historical analyses don’t help us much here.) I briefly mention Daumé and Campbell, as well, and Greenberg, to mention typological distribution – but I discount this as good evidence, given the exoteric languages that are most common, and complexity and cultural byproducts that would muddy up the data. I actually make an error in my abstract about this, so here’s my first apology for that (I made one in my laryngeal abstract, as well, misusing the word opaque. One could argue Sean isn’t really losing his edge.)

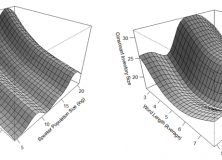

So, after all that, what are we left with? No solid proof against the evolution of morphology early, but a lot of functions that would seem to stand it firmly in the semantic neural mapping phase, tied to proto-morphology, which would have to be simultaneous to protosyntax. What I would love to do after this is run simulations about using invisible syntax versus visible morphological agreement for marking grammatical relations. The problem, of course, is that simulations probably won’t help for long distance dependencies, I don’t know how I’d frame that experiment, and using human subjects would be biased towards syntax, as we all are used to using that more than morphology, now, anyway. It’s a tough pickle to crack (I’m mixing my metaphors, aren’t I?)

—

And that sums up what my talk will be doing. Comments welcomed, particularly before the talk, as I can then adjust accordingly. I wrote this fast, because I’ll probably misspeak during the talk as well – so if you see anything weird here, call me out on it. Cheers.

*I believe in a gradual evolution of language, not a catastrophic one. Thank Hurford for this awesome phrase.

Selected References

Carstairs-McCarthy, A. (2010). The Evolution of Morphology. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Corbett, G. (2006). Agreement. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Heine, B., and Kuteva, T. (2007). The Genesis of Grammar. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Hurford, J.R. (2002). The Roles of Expression and Representation in Language Evolution. In A. Wray (Ed.) The Transition to Language (pp. 311–334). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lupan, G. & Dale, R (2009). Language structure is partly determined by social structure Social and Linguistic Structure.