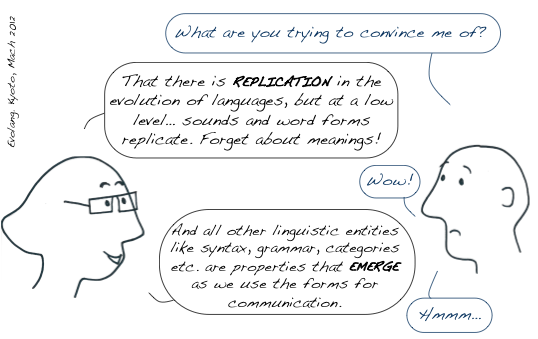

Now that the replicator meme is out and about I’ve got more to say. I’m going to republish two more posts from my 2010 cultural evolution series. These posts are about music. I have various reasons for using music as my cultural evolution conceptual sandbox. For one thing, it means that I don’t have to contend with semantic meanings arbitrarily associated with bits of music. In music, all we’ve got is the physical signal.

In these two posts I choose, not a simple musical example but, rather, a complex one, something jazz musicians know as Rhythm Changes. While I could talk about the four-note motif Beethoven used to construct the first movement of his Fifth Symphony, which is a memetic favorite, that’s too easy. Thinking about it won’t stretch our intuitions about the memetic properties of mere physical things. That motif has four notes, with specific durations and specific note-to-note pitch relationships.

Rhythm Changes isn’t like that. It’s an abstract property of a sound stream. There is now specific number of notes, no specific durations, and no specific note-to-note pitch relationships. Thousands upon thousands of specific musical streams, many quite different from one another, have exemplified the properties of Rhythm Changes.

In the previous post (in this series) I argued memes, the cultural parallel to the biological gene, are those physical properties of objects, events, and processes that allow different individuals to coordinate their participation in those things. In this view, memes are not physical objects, like genes, that spread through a population. Rather, memes are about sharability; they are physical properties that can easily be identified by human nervous systems and thus be the basis for shared (cultural) activity.

In that post I considered a very basic case, people making noise at regular intervals. In that case we have two memes, period (the interval between “hits”) and phase (the relationship between streams of hits by different individuals). Now I want to consider a considerably more complex case, the entity jazz musicians know as Rhythm Changes. This entity assumes that, for a given performance, period length and phase value are agreed upon. In fact it assumes a lot more. We’re dealing with a whole lot of memes here.

But I don’t want to get hung up in those details. I just want to characterize Rhythm Changes in a reasonable way and explain just why I insist that we regard Rhythm Changes as a structured collection of physical properties that can be ascribed to a stream of sound. While it would be nice to characterize Rhythm Changes using the language of acoustics, it’s not at all clear to me that we’ve got the necessary concepts. In any event, if we do, I don’t know them. Instead, I’ll couch my description in the schematic terms jazz musicians tend to use when talking about their craft; these terms are derived, in part, from descriptive and analytic concepts developed for European art music (i.e. classical music).

I’m going do this in two posts, the first will be confined to Rhythm Changes itself. The second will consider how Rhythm Changes came into being and how it functions in the popular music system. Continue reading “Wild Replicator’s Got Funky Rhythm, Part 1”