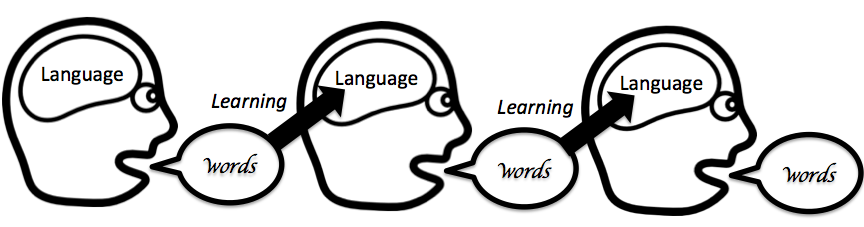

There is not currently a coursera on Language Evolution, so as a vague substitute, I thought I’d do a run down of places on the internet you can find some pretty decent free lectures on the evolution of language by some pretty big names.

1) The first are the videos of the plenaries from last year’s EvoLang conference in Kyoto. http://ocw.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/international-conference-en/31/video-en

I’m posting the direct links to all the videos because the above link keeps breaking:

| 1 | Massimo, Piattelli-Palmarini Three Models (and a Half) for the Description of Language Evolution |

Video |

| 2 | Minoru Asada Towards Language Acquisition by Cognitive Developmental Robotics |

Video |

| 3 | Cedric Boeckx Homo Combinans |

Video |

| 4 | Simon Kirby Why Language Has Structure: New Evidence from Studying Cultural Evolution in the Lab and What It Means for Biological Evolution |

Video |

| 5 | Jenny Saffran Out of the Brains of Babes: Domain-general Learning Mechanisms and Domain-specific Systems |

Video |

| 6 | Simon Fisher Molecular Windows into Speech and Language |

Video |

| 7 | Russell Gray The Evolution of Language Without Miracles |

Video |

| 8 | Rafael Núñez The Irreducible Semantic Communicative Drive |

Video |

| 9 | Tetsuro Matsuzawa Outgroup: The Study of Chimpanzees to Know the Human Mind |

Video |

| 10 | Tom Griffiths Neutral Models for Language Evolution。 |

Video |

| 11 | Terrence Deacon Neither Nature nor Nurture: Coevolution, Devolution, and Universality of Language |

Video |

The videos for the biolinguistics workshop can be found here: http://ocw.kyoto-u.ac.jp/en/international-conference-en/30/video-en

3) The videos from 2011’s ProtoLang can be viewed here: http://www.protolang.umk.pl/videos_and_links

There’s a link to the videos from 2009’s protolang at the bottom of that too, but they all seem to be broken. But you can actually still find them by searching for the author’s name on http://tv.umk.pl/

For example, searching Bart de Boer, you can find: http://tv.umk.pl/#movie=521

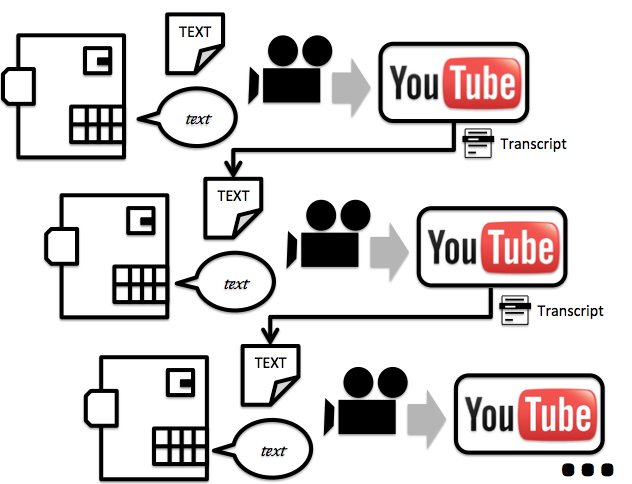

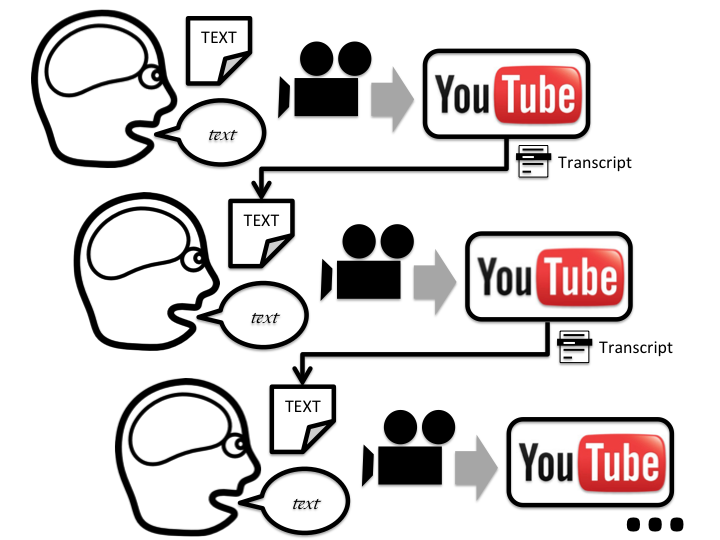

4) YouTube.

Highlights include Simon Kirby’s inaugural lecture at Edinburgh University, Kenny Smith at the University of Southampton earlier this year, more Terence Deacon, Luc Steels on robots and loads of other stuff, I am sure you are capable or googling the names of some language evolution folk.

Also, you can watch bbc horizon’s why do we talk featuring Techumseh Fitch, Simon Kirby and others here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=75XxjJYuV7I&list=PL9DD35E568234CA7F

And by request in the comments: Peter Richerson – How Possibly Language Evolved http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zxJMtZUaeZU

If anyone else has some good video resources please add them in the comments!