It’s over but there’s loads of cool papers I didn’t cover. Below is probably not a definitive list because there are SO MANY papers here, but here’s a good flavour of of the more language evolutiony offerings. In no particular order.

Language and Gesture Evolution by Call, Goldin-Meadows, Hobaiter, Liebal and Tomasello

Abstract:

In humans, gestural communication is closely intertwined with language: adults perform a variety of manual gestures, head movements and body postures while they are talking, children use gestures before they start to speak, and highly conventionalized sign systems can even replace spoken language. Because of this role of gestures for human com-munication, theories of language evolution often propose a gestural origin of language. In searching for the evolutionary roots of language, a comparative approach is often used to investigate whether any precursors to human language are also present in our closest relatives, the great apes, because of our shared phylogenetic history. Therefore, the aim of this symposium is to present recent progress in the field of language evolution from both a developmental and compa-rative perspective and to discuss the question if and to what extent a comparison with nonhuman primates is suitable to shed light on possible scenarios of language evolution.

Abstract:

When English speakers successively pile-sort colors, their sorting recapitulates an independently proposed hierarchy of color category evolution during language change (Boster, 1986). Here we extend that finding to the semantic domain of spatial relations. Levinson et al. (2003) have proposed a hierarchy of spatial category evolution, and we show that English speakers successively pile-sort spatial scenes in a manner that recapitulates that proposed evolutionary hierarchy. Thus, in the spatial domain, as in color, proposed universal patterns of language change based on cross-language observations appear to reflect general cognitive forces that are available in the minds of speakers of a single language.

Abstract:

Systematicity is a basic property of language and other culturally transmitted behaviours. Utilising a novel experimental task consisting of initially independent sequence learning trials, we demonstrate that systematicity can unfold gradually via the process of cultural transmission.

Experimental insights on the origin of combinatoriality by Roberts and Galantucci

Abstract:

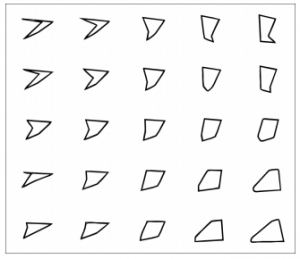

Combinatoriality—the recombination of a small set of basic forms to create an infinite number of meaningful units—has long been seen as a core design feature of language, but its origins remain uncertain. Two hypotheses have been suggested. The first is that combinatoriality is a necessary solution to the problem of conveying a large number of meanings; the second is that it arises as a consequence of conventionalisation. We tested these hypotheses in an experimental-semiotics study. Our results supported the hypothesis based on conventionalisation but offered little support for the hypothesis based on the number of meanings.

Combinatorial structure and iconicity in artificial whistled languages by Verhoef, Kirby and de Boer

Abstract:

This article reports on an experiment in which artificial languages with whistle words for novel objects are culturally transmitted in the laboratory. The aim of this study is to investigate the origins and evolution of combinatorial structure in speech. Participants learned the whistled language and reproduced the sounds with the use of a slide whistle. Their reproductions were used as input for the next participant. Cultural transmission caused the whistled systems to become more learnable and more structured. In addition, two conditions were studied: one in which the use of iconic form-meaning mappings was possible and one in which the use of iconic map- pings was experimentally made impossible, so that we could investigate the influence of iconicity on the emergence of structure.

Linguistic structure is an evolutionary trade-off between simplicity and

expressivity by Smith, Tamariz and Kirby

Abstract:

Language exhibits structure: a species-unique system for expressing complex meanings using complex forms. We present a review of modelling and experimental literature on the evolution of structure which suggests that structure is a cultural adaptation in response to pressure for expressivity (arising during communication) and compressibility (arising during learning), and test this hypothesis using a new Bayesian iterated learning model. We conclude that linguistic structure can and should be explained as a consequence of cultural evolution in response to these two pressures.

Communicative biases shape structures of newly acquired languages by Fedzechkina, Jaeger and Newport

Abstract:

Languages around the world share a number of commonalities known as language universals. We investigate whether the existence of some recurrent patterns can be explained by the learner’s preference to balance the amount of information provided by the cues to sentence meaning. In an artificial language learning paradigm, we expose learners to two languages with optional case-marking – one with fixed and one with flexible word order. We find that learners of the flexible word order language, where word order is uninformative of sentence meaning, use significantly more case-marking than the learners of the fixed word order language, where case is a redundant cue. The learning outcomes in our experiment parallel a variety of typological phenomena, providing support for the hypothesis that communicative biases can shape language structures.

Regularization behavior in a non-linguistic domain by Ferdinand, Thompson, Kirby and Smith

Abstract:

Language learners tend to regularize unpredictable variation and some claim that is due to a language-specific regularization bias. We investigate the role of task difficulty on regularization behavior in a non-linguistic frequency learning task and show that adults regularize variable input when tracking multiple frequencies concurrently, but reliably reproduce the variation they have observed when tracking one frequency. These results suggest that regularization behavior may be due to domain-general factors, such as memory limitations.

Abstract:

Communication systems reliably self-organize in populations of interacting agents under certain conditions. The various fields which model this – game theory, cognitive science and evolutionary linguistics – make different assumptions about the learning and behavioral processes which are responsible. We created an exemplar-based framework to directly compare these approaches by reproducing previously published models. Results show that a number of mechanisms are shared by the systems which can construct optimal communication. Three general factors are then proposed to underlie any self-organizing learned system.

Abstract:

Models of cognitive processes often include simplifications, idealisations, and fictionalisations, so how should we learn about cognitive processes from such models? Particularly in cognitive science, when many features of the target system are unknown, it is not always clear which simplifications, idealisations, and so on, are appropriate for a research question, and which are highly misleading. Here we use a case-study from studies of language evolution, and ideas from philosophy of science, to illustrate a robustness approach to learning from models. Robust properties are those that arise across a range of models, simulations and experiments, and can be used to identify key causal structures in the models, and the phenomenon, under investigation. For example, in studies of language evolution, the emergence of compositional structure is a robust property across models, simulations and experiments of cultural transmission, but only under pressures for learnability and expressivity. This arguably illustrates the principles underlying real cases of language evolution. We provide an outline of the robustness approach, including its limitations, and suggest that this methodology can be productively used throughout cognitive science. Perhaps of most importance, it suggests that different modelling frameworks should be used as tools to identify the abstract properties of a system, rather than being definitive expressions of theories.

And last but not least…replicated typo’s very own Sean Roberts with A Bottom-up approach to the cultural evolution of bilingualism

Abstract:

The relationship between individual cognition and cultural phenomena at the society level can be transformed by cultural transmission (Kirby, Dowman, & Griffiths, 2007). Top-down models of this process have typically assumed that individuals only adopt a single linguistic trait. Recent extensions include ‘bilingual’ agents, able to adopt multiple linguistic traits (Burkett & Griffiths, 2010). However, bilingualism is more than variation within an individual: it involves the conditional use of variation with different interlocutors. That is, bilingualism is a property of a population that emerges from use. A bottom-up simulation is presented where learners are sensitive to the identity of other speakers. The simulation reveals that dynamic social structures are a key factor for the evolution of bilingualism in a population, a feature that was abstracted away in the top-down models. Top-down and bottom-up approaches may lead to different answers, but can work together to reveal and explore important features of the cultural transmission process.