This is a guest post by Joses Ho.

Science fiction has been called “the fiction of ideas”. In this series of blog posts we catalogue a (non-exhaustive) list of works in the genre that explore ideas about language and linguistics.

Science fiction (abbreviated SF amongst devotees) has been called “the fiction of ideas”. And what a pantheon of eye-glazing, heart-palpitating, and brain-melting ideas: time travel, cyborg consciousness, alien invasions. However, does SF go further than mere fictive investigation of cool concepts? Can SF be a fiction of ideas about ideas?

One such idea about ideas, familiar to anyone who paid attention in any introductory undergraduate lecture on linguistics or cognitive science, is linguistic relativity (also popularly known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis). Briefly, for the benefit of the rest of us who fell asleep in aforementioned lectures, it conjectures that the language you speak determines and shapes the way you think and the way you perceive “the universe around you” (Star Trek fans will instantly think of the Tamarian language, which can only be understood if you know the cultural references). Below I discuss 3 works that play with this idea.

1. Story of Your Life

Our first example of a SF piece that explores linguistic relativity is the novella Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang, first published in 1998, and soon to be adapted into a movie.

An alien race of Heptopods has landed on Earth, and our protagonist and narrator, Louise Banks, is a linguist contacted by the US military to learn their language and communicate with them. As the tale unfolds, Louise’s very view of reality is radically altered as she masters the written language of the Heptopods. Louise tells the reader:

…Even though I’m proficient with [written Heptapod], I know I don’t experience reality the way a heptapod does. My mind was cast in the mould of human languages, and no amount of immersion in an alien language can completely reshape it. My world-view is an amalgam of human and heptapod.

Chiang brilliantly employs an unusual narrative structure to reflect this, and we are given a glimpse into how linguistic relativity might actually work in real time.

This novella is also characteristic of Chiang’s SF work, which consists solely of short stories, written with economic prose and crisp exposition fined-tuned to deliver devastatingly satisfying endings.

2. Words and Music

Another shorter example is Words And Music by Ronald D. Ferguson. Describing an alien species known as the Utmano, the narrator tells us:

.., Utmano translation doesn’t compare well to translations among human languages. The Utmano language has a peculiar view of tense, you know, past, present, future, in its sentences — well maybe not sentences, but the complete-thought communication structure. Psychologists claim that the Utmano have a lingering, vivid, recent memory combined with a mild prescience that blends with their perception of the ‘now’. It sounds like gobbledegook, but they claim that the Utmano idea of the present spans from the middle of last week to a couple of hours from now.

The above expository paragraph is more typical of how linguistic relativity is explored in SF. While Words and Music doesn’t quite go as far as Chiang does in using the narrative structure itself to illustrate the alien mode of perception being described, Ferguson uses a novel framing device to pack quite a bit of story and exposition into a short space.

3. Embassytown

Our last selection is novel by celebrated SF writer China Miéville. Embassytown was his ninth novel and features the Ariekei, an alien race whose spoken language involved vocalizing two words simultaneously.

This is not a terribly new idea; Ferguson makes mention of this in Words and Music. In Ferguson’s story, the humans successfully apply the obvious solution (used by real-world linguists in the field as well, and mentioned in Story of Your Life) to the problem of communicating with such an alien race: use pre-recorded or synthetic speech. But Miéville won’t have that.

Synthetic speech is indiscernible to the Ariekei, because they require an actual mind to be uttering each (simultaneous) syllable. And so, the intergalatic human Ambassadors are specially-bred twins whose minds are linked, able to speak with two mouths and one mind. (If that idea doesn’t make your eyes glaze and brain melt, you are probably an Ariekei.)

These Ambassadors are the only ones who can communicate with the Ariekei, and are crucial to human-Ariekei diplomatic and trade relations. The plot gets truly interesting when a new pair of ambassadors arrives to the city of the novel’s title. These two individuals are not genetically identical, but have been selected for linkage based on their high degree of empathy. When they speak the alien language (which Miéville simply christens, a little pompously, “Language”), the effect on the Ariekei is unprecedented: they become addicted to the new Ambassador’s speech.

The rest of the novel runs along on a action-filled plot, and still manages to raise questions about mind, intelligence, and the very nature of language.

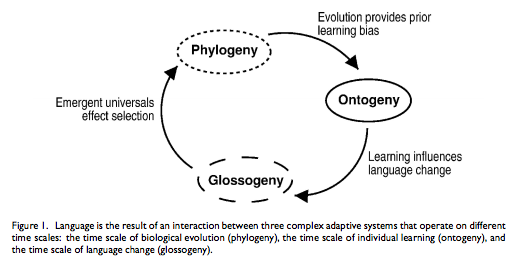

However, despite how strange the Ariekei appear, there are cases of human language use that are similar to the way their “Language” functions. Humans actually can speak two things simultaneously, using signed language and spoken language. This is called “code-blending”. Interestingly, the two words they speak and sign simultaneously can refer to different things, or are “semantically non-equivalent.”

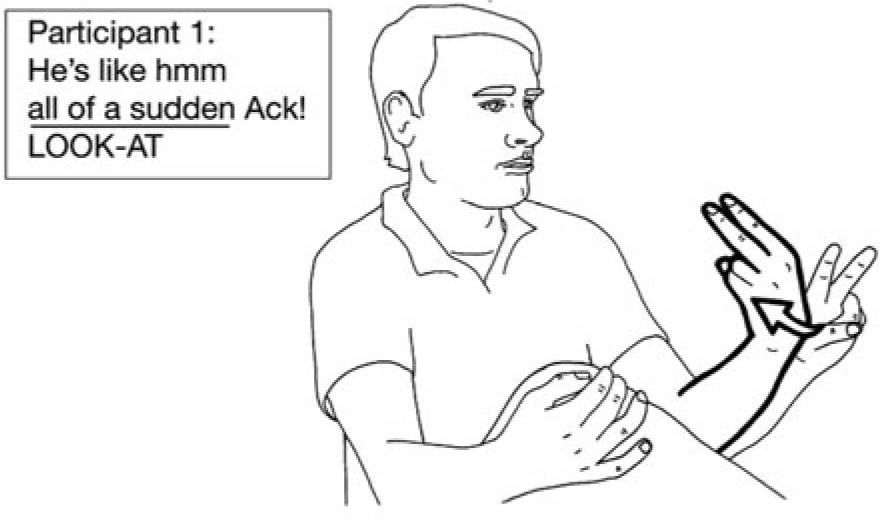

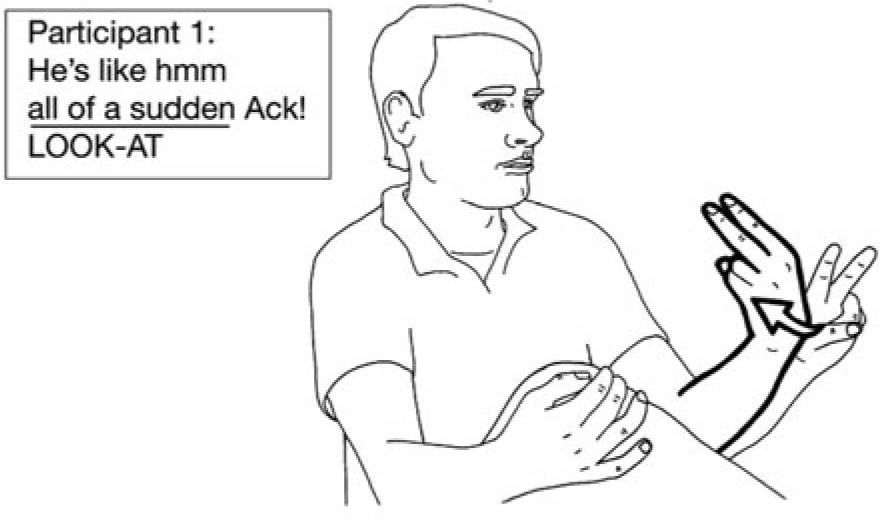

An example is given below; the capitalised text on the lower line represents the signs used (taken from Emmorey, Bornstein & Thompson (2005) and Emmorey et al., 2008).

In this picture, a man is describing a scene between the cartoon characters Sylvester the cat and Tweety the bird.

“He” refers to Sylvester who is nonchalantly watching Tweety swinging inside his bird cage on the window sill. Then all of a sudden, Tweety turns around and looks right at Sylvester and screams (“Ack!”). The sign glossed as LOOK-AT-ME is produced at the same time as the English words “all of a sudden.” [The emphasis is mine, and not in the original academic paper.]

The speaker is using both signed language and spoken language to narrate how Tweety suddenly turns to look at Sylvester sneaking up on him. So the simultaneous speech sounds of Miéville’s Ariekei might not be that far off from actual human communication.

This cross-modal flexibility in human communication may suggest that, no matter how intertwined language and thought may be, there may be no language that we truly won’t be able to understand.

Further reading

We are by no means the only ones to have noticed how linguistics is a well-explored topic in SF. There is an excellent entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction devoted to linguistics as a topic and a trope in science fiction; its exhaustive breadth (it is an encyclopedia article, after all) is remarkable, listing several source texts in a polished tone, although it omits to mention the specific pieces of fiction we have discussed above.

Dr. Maggie Browning, an associate professor in linguistics at Princeton, has compiled a bullet-point list on her website. The book recommendation site Goodreads features as well a crowdsourced list titled “Science Fiction using Languages or Linguistics as a Plot Device”. Both places are invaluable starting points for relevant primary material.

Last, but not least, there is the Alien Tongues blog, written by two graduate students in linguistics, and focussing on the links between SF and linguistics. It has several posts on the constructed languages found in much of SF.

We hope you have enjoyed this post, which we hope this will not be the last on this fascinating topic!

Joses Ho is a currently pursuing a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Oxford, and as a visiting researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. His interests also include science fiction, theology, and film. His fiction and poetry have appeared, respectively, in Nature Futures and Quarterly Literary Review Singapore. Follow him on Twitter; his handle is @jacuzzijo.