This is a guest post by Jeremy Collins

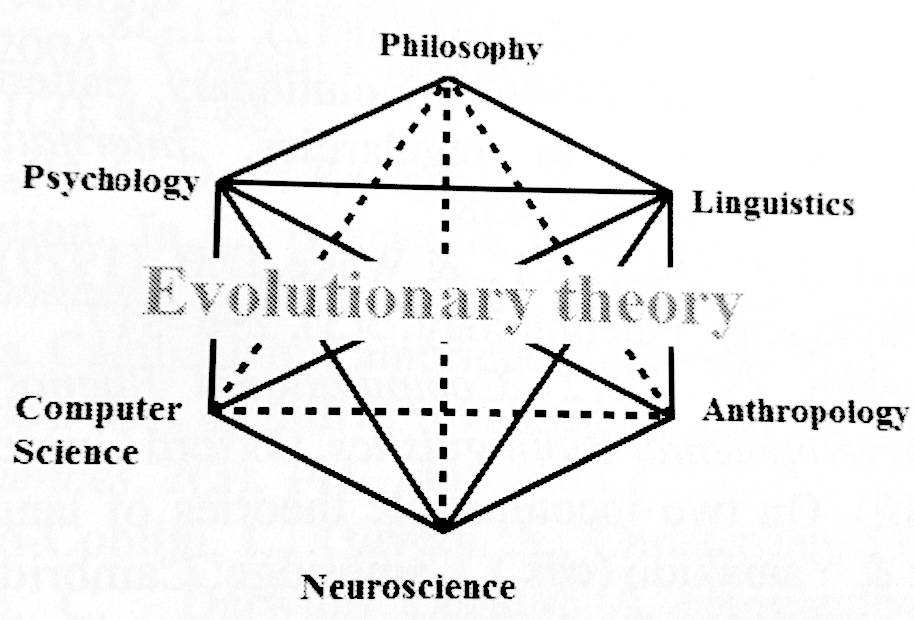

Hauser, Yang, Berwick, Tattersall, Ryan, Watamull, Chomsky and Lewontin have recently published an article entitled ‘The Mystery of Language Evolution‘ (see also Sean’s post), in which they argue that theories of language evolution today are ‘accompanied by a poverty of evidence’ and that ‘the most fundamental questions about the origins and evolution of our linguistic capacity remain as mysterious as ever’. Rather than criticise their article, I thought I would summarise what I think some of the empirical advances have been, in defence of the field. A few well-known lines of research seem to have fleshed out some details of how language evolved, even if they are still in their infancy.

1. Vocal learning in other species.

Culturally transmitted song has evolved multiple times in various bird species, dolphins and bats. Although Hauser et al. dismiss bird song as irrelevant in that it is ‘finite’ and lacks compositional meaning (p.6), these species shed light on why culturally transmitted vocalisation evolved in humans. These species typically live in groups of unrelated individuals, for instance, who co-operate in foraging. The complexity of their learnt song may have evolved in the context of recognising and being altruistic towards kin (Sharp et al. 2005) (or by extension any unrelated members who exploit this altruism by managing to acquire the song of the group). In a similar way, much of the complexity and cultural variability of human language may have developed in the context of in-group identification, such as our ability to detect subtle variations in accent (Fitch 2004). While sexual selection is an important reason for the evolution of vocal learning in some of these species, it is unlikely to be the main driving force in humans given the lack of sexual dimorphism in language use, in contrast with song birds (Fitch 2004), although its role in human pair bonding is similar to pair bonding in monogamous parrot species (Pepperberg 1999). Pepperberg (1999) showed that African Grey Parrots can learn to use spoken words and correctly answer questions involving abstract semantic categories, and with some understanding of syntax, showing how bird vocal learning is not necessarily as qualitatively different from human language acquisition as Hauser et al. suggest.

2. The genetics of language.

The precise relationships between genes and language are unknown, as the authors say; but specific language disorders at least show that syntax and fluency of speech are heritable, which is an advance in its own right. Vocabulary size and vocabulary acquisition patterns (e.g. rate of learning words at different ages in infancy) have also been shown to be heritable (Stromswold 2001). Although these are not genes ‘for’ these specific linguistic traits,they are likely to have been selected for partly in the context of language use, given the vast difference in syntactic complexity and vocabulary size between human languages and languages that primates, such as Kanzi or Nim Chimpsky, can acquire.

3. The neurobiology of language and tool use.

The neural circuitry for language is likely to have been co-opted in part from the transmission and use of tools; they both involve complex motor actions and have been suggested to use similar areas of the brain such as Broca’s area, which is activated in experiments involving complex tool manufacture (Higuchi et al. 2009), and which is often lateralised differently in the brain in left-handed individuals (Knecht et al. 2000). The prevalence of gesture in spoken languages, the fact that we can acquire complex sign languages, and the range of innate gestures in gorillas and chimpanzees (contrasted with their absence of vocalization) suggest that gesture may have been a platform for the evolution of language, and manual dexterity for the evolution of recursive syntax in particular (Arbib 2012). If the authors want an evolutionary origin for ‘discrete infinity’, this is one candidate.

4. The study of sound symbolism.

Three lines of evidence suggest that sound-symbolism helped spoken language evolve: robust sound-meaning pairings tested across 6000 languages, controlling for language family and region (such as proximal demonstratives and words for ‘small’ using a front vowel) (Blasi et al. 2014); rich systems of ideophones, namely words similar to onomatopoeia but which go beyond sound in being able to depict appearance, texture, motion, tastes, and emotions, in language families in Africa, Southeast Asia and the Americas (Dingemanse 2012); and innate associations of sounds and shapes independent of language, as suggested by ideophones, and the bouba/kiki and similar tests (Ramachandran 2013).

5. The study of the diversity of grammar.

As an example, grammatical categories regularly develop from simpler, lexical categories, in ways that recur across many language families: e.g.pre-/post-positions develop from abstract nouns and verbs, adjectives develop from forms of nouns and verbs, tense and aspect markers develop from adverbs or nominalizers (e.g. the development of English ‘-ing’ from a nominal affix to a gerund marker to a participle marker), and so on (Heine and Kuteva 2007). Cross-linguistic work can therefore shed light on what the first languages may have been like, such as having more weakly differentiated grammatical categories (e.g. collapsing adjectives or adpositions with nouns and verbs). Studies on patterns of basic word order suggest that that subject-object-verb order is likely to have been used, given its dominance in spoken languages today when controlling for geography and language family (Gell-Mann and Ruhlen 2011, Dryer 1992), and the way that people spontaneously converge on that word order when gesturing (Goldin-Meadow et al. 2008). Languages spoken by small populations tend to develop case-marking and other complex morphology (Lupyan and Dale 2010), suggesting that this may also have been a feature of early languages. Increasingly detailed surveys of linguistic diversity can help generate hypotheses like these, and hopefully soon allow ways of testing them.

Hauser et al.’s paper has some valid criticisms of the field (such as of models of the cultural evolution of compositionality, and the evidence for Neanderthal language), but I think that their assessment that ‘the fundamental questions remain as mysterious as ever’ is too pessimistic. Others have noted that none of the authors were at the last Evolution of Language conference, which is not surprising given what I remember of meeting Charles Yang, the second author on that paper, at the previous conference in Kyoto. He was sitting gloomily at dinner with a group of Japanese generativists, who were not talking. I asked him whether he had enjoyed any of the talks, and he said ‘Almost none. Their notion of language is so…impoverished.’ He brightened up when the conversation turned back to Chomsky, whom he had had dinner with recently. ‘We drank a lot of wine. And Noam had two desserts.’

Jeremy Collins designs kitchens and bathrooms at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. His homepage is here.

References

Arbib M. A. (2012) Tool use and constructions. Behav Brain Sci. 35(4):218-9.

Blasi et al. (2014) Sound symbolism and the origins of language. IN

Cartmill, Roberts, Lyn & Cornsih (Eds. ) The Evolution of Language: Proceedings of the 10th EvoLang Conference.

Dingemanse, Mark. 2012. “Advances in the Cross-Linguistic Study of

Ideophones.” Language and Linguistics Compass 6 (10): 654–72.

doi:10.1002/lnc3.361.

Dryer, M. (1992). The Greenbergian word order correlations. Language, pages 81–138.

Fitch, W. T. (2004). The evolution of language. In: The Cognitive Neurosciences (3rd Edition, Ed. by Gazzaniga, M.). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press

Gell-Mann, M. and Ruhlen, M. (2011). The origin and evolution of word order. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 108(42):17290–17295.

Goldin-Meadow, S., So, W. C., O ̈zyu ̈rek, A., and Mylander, C. (2008). The natural order of events: How speakers of different languages represent events nonverbally. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 105(27):9163–9168.

Higuchi, S., Chaminade, T., Imamizu, H., and Kawato, M. (2009). Shared neural correlates for language and tool use in broca’s area. Neuroreport, 20(15):1376–1381.

Knecht, S., Dr ̈ager, B., Deppe, M., Bobe, L., Lohmann, H., Fl ̈oel, A., Ringelstein, E.-B., and Henningsen, H. (2000). Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain, 123(12):2512–2518.

Lupyan, G. and Dale, R. (2010). Language structure is partly determined by social structure. PLoS ONE, 5(1):e8559.

Pepperberg, I.M. (1999). The Alex Studies: Cognitive and Communicative Abilities of Grey Parrots. Harvard.

Sharp, S.P., McGowan, A., Wood, M.J., and Hatchwell, B.J. (2005). Learned kin recognition cues in a social bird. Nature, 434:1127-1130

Stromswold, K. (2001). The heritability of language: A review and metaanalysis of twin, adoption, and linkage studies. Language, 77(4):647–723.