I haven’t forgotten my on-going series of posts on the direction of cultural evolution; you know, the one that started with Matt Jockers’ Macroanalysis? But I’ve been busy with other things. Here’s another post to add to that pile. I’m not yet burned out on culture, but lordy lordy I’m gettin’ there. But there’s a few more ideas I’ve got to get out there before I can hang up these particular shoes. If only for awhile.

* * * * *

What do I mean by cultural beings? To be honest, I’m not quite sure. Let’s start by being conservative about it – though just what “conservative” means amid this kind of intellectual craziness is a curious question – let’s say that novels, like those Jockers considered, are cultural beings. So are musical performances, like those driving American culture; they’re also cultural beings. Cultural beings are things like THAT, but note that THAT ranges over culture in general and not merely so-called high culture. After all, most of Jockers’ novels and most of those musical performances are not high cultural phenomena. Many are distinctly low and vulgar, while others are merely middlebrow.

I am using “cultural being” as a term of art. It designates not merely the cultural artifact, whether it is a long narrative imprinted in a codex, a musical composition inscribed on score paper, or even a performance merely floating in the air and then gone forever, except for memories of it. Those physical things are just packages or envelopes, other terms of art I’m hereby proposing. And those packages or envelopes “contain” coordinators, the cultural analog to biological genes.

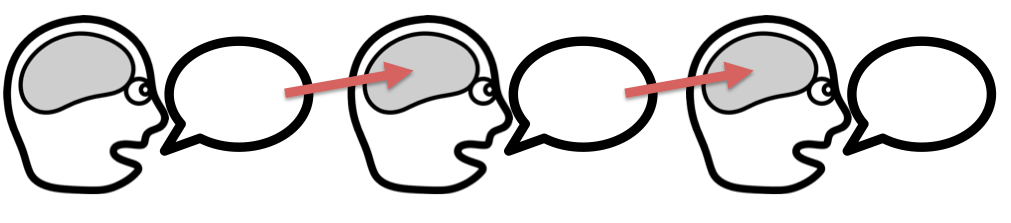

When we read texts or listen to (even participate in) performances, the coordinator packages elicit phantasms in the mind/brain. It is the phantasm that gives pleasure, and so leads to a desire for repetition, or not, in which case the package that elicited it is forgotten. Those phantasms belong to cultural beings as well. If you will, the package of coordinators is the body of a cultural being while the phantasm is its soul.

The Ontology of Culture

When I talk about the ontology of culture, then, I mean these entities and the relations between them: cultural beings, packages or envelopes, coordinators, and phantasms. The relations between them are complex and subtle and I don’t pretend to grasp them, though I’ve been writing and thinking about the at least since my book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil, if not longer.

The overall relationship among them, however, is given by the evolutionary dynamic of blind variation and selective retention:

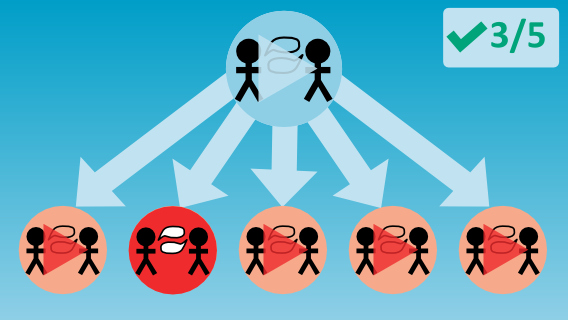

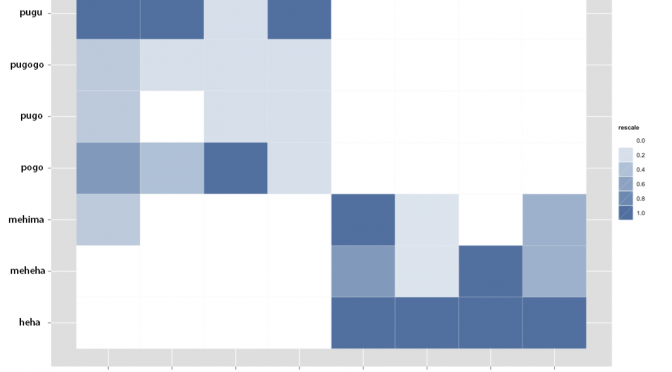

The evolution of cultural beings proceeds by blind variation among coordinators and selective retention of phantasms.

But what does it mean to retain a phantasm? Phantasms are (collective) mental events. They come and they go. How can they be retained?

They can’t. But they can be remembered and if the memory is compelling, one can re-create the phantasm. How do you do that? You re-experience the package of coordinators that gave rise to the phantasm in the first place. And so we have this modified formulation:

The evolution of cultural beings proceeds by blind variation among coordinators and selective retention of packages or envelopes.

Will that work? Will it do the job? I don’t know. I just thought it up.

Let us remember, however, that phantasms are the cultural analog to the biological phenotype. And what is retained in biological evolution is not the individual phenotypes. They all die and the matter of which they were composed rots. What’s retained is the phenotypic scheme, the Bauplan that emerges from a developmental process regulated by the genotype.

With that in mind, let’s move on. Continue reading “Cultural Beings, the Ontology of Culture, and a Return to Books and Blues”