A new working paper. Downloads HERE:

- SSRN: http://ssrn.com/abstract=2640687

- Academia.edu: https://www.academia.edu/14723447/An_Inquiry_into_and_a_Critique_of_Dennett_on_Intentional_Systems

Abstract, contents, and introduction below:

* * * * *

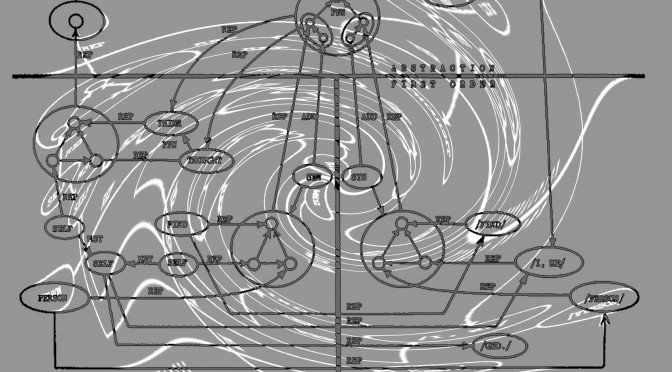

Abstract: Using his so-called intentional stance, Dennett has identified so-called “free-floating rationales” in a broad class of biological phenomena. The term, however, is redundant on the pattern of objects and actions to which it applies and using it has the effect of reifying the pattern in a peculiar way. The intentional stance is itself a pattern of wide applicability. However, in a broader epistemological view, it turns out that we are pattern-seeking creatures and that phenomenon identified with some pattern must be verified by other techniques. The intentional stance deserves no special privilege in this respect. Finally, it is suggested that the intentional stance may get its intellectual power from the neuro-mental machinery it recruits and not from any special class of phenomena it picks out in the world.

CONTENTS

Introduction: Reverse Engineering Dan Dennett 2

Dennett’s Astonishing Hypothesis: We’re Symbionts! – Apes with infected brains 6

In Search of Dennett’s Free-Floating Rationales 9

Dan Dennett on Patterns (and Ontology) 14

Dan Dennett, “Everybody talks that way” – Or How We Think 20

Introduction: Reverse Engineering Dan Dennett

I find Dennett puzzling. Two recent back-to-back videos illustrate that puzzle. One is a version of what seems to have become his standard lecture on cultural evolution, this time entitled

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=AZX6awZq5Z0

As such it has the same faults I identify in the lecture that occasioned the first post in this collection, Dennett’s Astonishing Hypothesis: We’re Symbionts! – Apes with infected brains. It’s got a collection of nicely curated examples of mostly biological phenomenon which Dennett crafts into an account of cultural evolution though energetic hand-waving and tap-dancing.

And then we have a somewhat shorter video that is a question and answer session following the first:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=beKC_7rlTuw

I like much of what Dennett says in this video; I think he’s right on those issues.

What happened between the first and second video? For whatever reason, no one asked him about the material in the lecture he’d just given. They asked him about philosophy of mind and about AI. Thus, for example, I agree with him that The Singularity is not going to happen anytime soon, and likely not ever. Getting enough raw computing power is not the issue. Organizing it is, and as yet we know very little about that. Similarly I agree with him that the so-called “hard problem” of consciousness is a non-issue.

How is it that one set of remarks is a bunch of interesting examples held together by smoke and mirrors while the other set of remarks is cogent and substantially correct? I think these two sets of remarks require different kinds of thinking. The second set involve philosophical analysis, and, after all Dennett is a philosopher more or less in the tradition of 20th century Anglo-American analytic philosophy. But that first set of remarks, about cultural evolution, is about constructing a theory. It requires what I called speculative engineering in the preface to my book on music, Beethoven’s Anvil. On the face of it, Dennett is not much of an engineer.

And now things get really interesting. Consider this remark from a 1994 article [1] in which Dennett gives an overview of this thinking up to that time (p. 239):

My theory of content is functionalist […]: all attributions of content are founded on an appreciation of the functional roles of the items in question in the biological economy of the organism (or the engineering of the robot). This is a specifically ‘teleological’ notion of function (not the notion of a mathematical function or of a mere ‘causal role’, as suggested by David LEWIS and others). It is the concept of function that is ubiquitous in engineering, in the design of artefacts, but also in biology. (It is only slowly dawning on philosophers of science that biology is not a science like physics, in which one should strive to find ‘laws of nature’, but a species of engineering: the analysis, by ‘reverse engineering’, of the found artefacts of nature – which are composed of thousands of deliciously complicated gadgets, yoked together opportunistically but elegantly into robust, self-protective systems.)

I am entirely in agreement with his emphasis on engineering. Biological thinking is “a species of engineering.” And so is cognitive science and certainly the study of culture and its evolution.

Earlier in that article Dennett had this to say (p. 236):

It is clear to me how I came by my renegade vision of the order of dependence: as a graduate student at Oxford, I developed a deep distrust of the methods I saw other philosophers employing, and decided that before I could trust any of my intuitions about the mind, I had to figure out how the brain could possibly accomplish the mind’s work. I knew next to nothing about the relevant science, but I had always been fascinated with how things worked – clocks, engines, magic tricks. (In fact, had I not been raised in a dyed-in-the-wool ‘arts and humanities’ academic family, I probably would have become an engineer, but this option would never have occurred to anyone in our family.)

My reaction to that last remark, that parenthesis, was something like: Coulda’ fooled me! For I had been thinking that an engineering sensibility is what was missing in Dennett’s discussions of culture. He didn’t seem to have a very deep sense of structure and construction, of, well, you know, how design works. And here he is telling us he coulda’ been an engineer.

Continue reading “An Inquiry into & a Critique of Dennett on Intentional Systems”