Note: Late on the evening og 7.20.15: I’ve edited the post at the end of the second section by introducing a distinction between prediction and explanation.

Thinking things over, here’s the core of my objection to talk of free-floating rationales: they’re redundant.

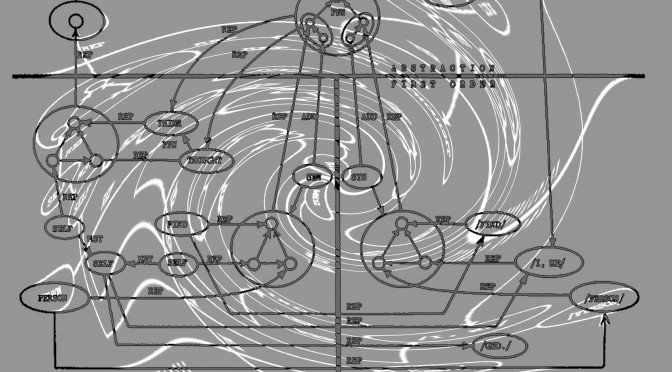

What authorizes talk of “free-floating rationales” (FFRs) is a certain state of affairs, a certain pattern. Does postulating the existence of FFRs add anything to the pattern? Does it make anything more predictable? No. Even considering the larger evolutionary context in which talk of FFRs adds nothing (p. 351 in [1]):

But who appreciated this power, who recognized this rationale, if not the bird or its individual ancestors? Who else but Mother Nature herself? That is to say: nobody. Evolution by natural selection “chose” this design for this “reason.”

Surely what Mother Nature recognized was the pattern. For all practical purposes talk of FFRs is simply an elaborate name for the pattern. Once the pattern’s been spotted, there is nothing more.

But how’d a biologist spot the pattern? (S)he made observations and thought about them. So I want to switch gears and think about the operation of our conceptual equipment. These considerations have no direct bearing on our argument about Dennett’s evolutionary thought, as every idea we have must be embodied in some computational substrate, the good ideas and the bad. But the indirect implications are worth thinking about. For they indicate that a new intellectual game is afoot.

Dennett on How We Think

Let’s start with a passage from the intentional systems article. This is where Dennett is imagining a soliloquy that our low-nesting bird might have. He doesn’t, of course, want us to think that the bird ever thought such thoughts (or even, for that matter, perhaps thought any thoughts at all). Rather, Dennett is following Dawkins in proposing this as a way for biologists to spot interesting patterns in the life world. Here’s the passage (p. 350 in [1]):

I’m a low-nesting bird, whose chicks are not protectable against a predator who discovers them. This approaching predator can be expected soon to discover them unless I distract it; it could be distracted by its desire to catch and eat me, but only if it thought there was a reasonable chance of its actually catching me (it’s no dummy); it would contract just that belief if I gave it evidence that I couldn’t fly anymore; I could do that by feigning a broken wing, etc.

Keeping that in mind, lets look at another passage. This is from a 1999 interview [2]:

The only thing that’s novel about my way of doing it is that I’m showing how the very things the other side holds dear – minds, selves, intentions – have an unproblematic but not reduced place in the material world. If you can begin to see what, to take a deliberately extreme example, your thermostat and your mind have in common, and that there’s a perspective from which they seem to be instances of an intentional system, then you can see that the whole process of natural selection is also an intentional system.

It turns out to be no accident that biologists find it so appealing to talk about what Mother Nature has in mind. Everybody in AI, everybody in software, talks that way. “The trouble with this operating system is it doesn’t realize this, or it thinks it has an extra disk drive.” That way of talking is ubiquitous, unselfconscious – and useful. If the thought police came along and tried to force computer scientists and biologists not to use that language, because it was too fanciful, they would run into fierce resistance.

What I do is just say, Well, let’s take that way of talking seriously. Then what happens is that instead of having a Cartesian position that puts minds up there with the spirits and gods, you bring the mind right back into the world. It’s a way of looking at certain material things. It has a great unifying effect.

So, this soliloquy way of mind is useful in thinking about the biological world and something very like it is common among those who have to work with software. Dennett’s asking us to believe that, because thinking about these things in that way is so very useful (in predicting what they’re going to do) that we might as well conclude that, in some special technical sense, they really ARE like that. That special technical sense is given in his account of the intentional stance as a pattern, which we examined in the previous post [3].

What I want to do is refrain from taking that last step. I agree with Dennett that, yes, this IS a very useful way of thinking about lots of things. But I want to take that insight in a different direction. I want to suggest that what is going on in these cases is that we’re using neuro-computational equipment that evolved for regulating inter personal interactions and putting it to other uses. Mark Changizi would say we’re harnessing it to those other purposes while Stanislaw Dehaene would talk of reuse. I’m happy either way. Continue reading “Dan Dennett, “Everybody talks that way” – Or How We Think”