Consider these three words: gavagai, gabagaí, gabagool. If you’ve been binge watching episodes in the Star Trek franchise you might suspect them to be the equivalent of veni, vidi, vici, in the language of a space-faring race from the Gamma Quadrant. The truth, however, is even stranger.

The first is a made-up word that is well-known in certain philosophical circles. The second is not quite a word, but is from Pirahã, the Amazonian language brought to our attention by ex-missionary turned linguist, Daniel Everett, and can be translated as “frustrated initiation,” which is how Everett characterized his first field trip among the Pirahã. The third names an Italian cold cut that is likely spelled “capicola” or “capocolla” when written out and has various pronunciations depending on the local language. In New York and New Jersey, Tony Soprano country, it’s “gabagool”.

Everett discusses first two in his wide-ranging new book, Dark Matter of the Mind: The Culturally Articulated Unconscious (2016), which I review at 3 Quarks Daily. As for gabagool, good things come in threes, no?

Why gavagai? Willard van Orman Quine coined the word for a thought experiment that points up the problem of word meaning. He broaches the issue by considering the problem of radical translation, “translation of the language of a hitherto untouched people” (Word and Object 1960, 28). He asks us to consider a “linguist who, unaided by an interpreter, is out to penetrate and translate a language hitherto unknown. All the objective data he has to go on are the forces that he sees impinging on the native’s surfaces and the observable behavior, focal and otherwise, of the native.” That is to say, he has no direct access to what is going on inside the native’s head, but utterances are available to him. Quine then asks us to imagine that “a rabbit scurries by, the native says ‘Gavagai’, and the linguist notes down the sentence ‘Rabbit’ (of ‘Lo, a rabbit’) as tentative translation, subject to testing in further cases” (p. 29).

Quine goes on to argue that, in thus proposing that initial translation, the linguist is making illegitimate assumptions. He begins his argument by nothing that the native might, in fact, mean “white” or “animal” and later on offers more exotic possibilities, the sort of things only a philosopher would think of. Quine also notes that whatever gestures and utterances the native offers as the linguist attempts to clarify and verify will be subject to the same problem.

As Everett notes, however, in his chapter on translation (266):

On the side of mistakes never made, however, Quine’s gavagai problem is one. In my field research on more than twenty languages—many of which involved monolingual situations …, whenever I pointed at an object or asked “What’s that?” I always got an answer for an entire object. Seeing me point at a bird, no one ever responded “feathers.” When asked about a manatee, no one ever answered “manatee soul.” On inquiring about a child, I always got “child,” “boy,” or “girl,” never “short hair.”

Later:

I believe that the absence of these Quinean answers results from the fact that when one person points toward a thing, all people (that I have worked with, at least) assume that what is being asked is the name of the entire object. In fact, over the years, as I have conducted many “monolingual demonstrations,” I have never encountered the gavagai problem. Objects have a relative salience… This is perhaps the result of evolved perception.

Frankly, I forget how I reacted to Quine’s thought experiment when I first read it as an undergraduate back in the 1960s. I probably found it a bit puzzling, and perhaps I even half-believed it. But that was a long time ago. When I read Everett’s comments on it I was not surprised to find that the gavagai problem doesn’t arise in the real world and find his suspected explanation, evolved perception, convincing.

As one might expect, Everett devotes quite a bit of attention to recursion, with fascinating examples from Pirahã concerning evidentials, but I deliberately did not bring that up in my review. Why, given that everyone and their Aunt Sally seem to be all a-twitter about the issue, didn’t I discuss it? That’s why, I’m tired of it and think that, at this point, it’s a case of the tail wagging the dog. I understand well enough why it’s an important issue, but it’s time to move on.

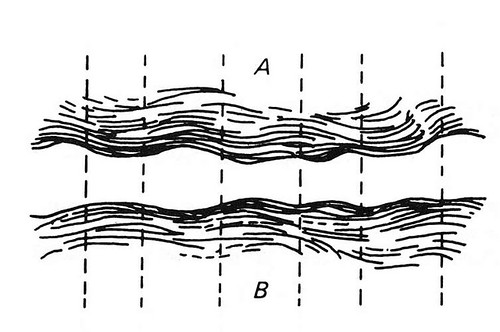

The important issue is to shift the focus of linguistic theory away from disembodied and decontextualized sentences and toward conversational interaction. That’s been going on for some time now and Everett has played a role in that shift. While the generative grammarians use merge as a term for syntactic recursion it could just as well be used to characterize how partners assimilate what they’re hearing with what they’re thinking. Perhaps that’s what syntax is for and why it arose, to make conversation more efficient–and I seem to think that Everett has a suggestion to that effect in his discussion of the role of gestures in linguistic interaction.

Anyhow, if these and related matters interest you, read my review and read Everett’s book.