![]() I went to a good talk almost a year ago at the Interfaces III conference at the University of Kent, and I said I’d write about it, but I never got around to it. The slides have been on my desktop ever since. Now that I have a couple hours to kill on the train coming back from the MPI in Nijmegen, here’s that promise fulfilled. I’m going mostly from the slides, so nicely sent to me, and any errors in the transcription from those are my own.

I went to a good talk almost a year ago at the Interfaces III conference at the University of Kent, and I said I’d write about it, but I never got around to it. The slides have been on my desktop ever since. Now that I have a couple hours to kill on the train coming back from the MPI in Nijmegen, here’s that promise fulfilled. I’m going mostly from the slides, so nicely sent to me, and any errors in the transcription from those are my own.

The evolution of numeral classifier constructions

Vipas Pothipath, Dept. of Thai, Chulalongkorn University

The talk was based on work done at both Chulalongkorm and the MPI for Evo. Anthr. in Leipzig, as well as on (then unpublished, although it might be now) Pothipath’s PhD thesis.

A number classifier is a morpheme typically appearing next to a numeral or a quantifier, categorizing the noun with which it co-occurs on a semantic basis. An example would be the Thai, where tua is the classifier:

- mǎ: sǎ:m tua

- dog three CLF (lit. ‘body’)

- three dogs

These can also be bound morphemes, and can co-occur with ordinal numerals or definitive markers. Pothipath focused on cardinal numerals, and defined numeral classifier constructions (NCCs) as syntactic constructions basically consisting of two core constituents, namely a cardinal numeral X and a numeral classifier Y. This case would be exemplified by the above Thai example, which is just as grammatical when mǎ: ‘dog’ is dropped and only the numeral and classifier remain. Now, based on WALS, these exist in many languages across the world (although not so much in Europe), and are sometimes optional and occasionally obligatory. The sample size was only 56 languages, so there might be more widespread variation. Pothipath claims that the optional/obligatory split shows a possibility of a typologial continuum, and that the evolution can be shown using an evolutionary ladder.

This continuum wouldn’t work if there weren’t different types of NCCs. He outlines these (although the names given here are mostly my own):

- Repeater: Where a noun is used as the numeral classifier for the noun itself, particularly when there isn’t a suitable classifier for that noun. (I wish there had been a bit of a more explicit statement about how this isn’t just a switch in syntax for noun and number, as can be seen in the example given (fǽm) hâ: fǽm ‘(file) five files’.)

- Free form classifier: Where there is a single form used for certain nouns that isn’t related morphologically or lexically synchronically.

- Affixal classifier: Like above, but bound to the numeral, as in mat=tol ‘CLF=three’ in Taba. (Bowden, 2001)

- Obligatory affixal classifier: Here, the classifier is a dependant morpheme on the numeral, as in maq-ond ‘CLF-one’ in Malto. (Steever 1998)

- Joined (unanalyzable) classifier: Where a different lexical form is used for the numeral depending on the nature of the noun.

Now, among the languages Pothipath looked at, some showed more than one morphological type of NCC. This might be a sign that, under the theory of grammaticalisation, free forms develop into the final lexically closed type of classifier. He goes on to show, using diachronich examples, where different languages show this change. Interestingly, he cites Hurford (2001) as a justification for the affixation of classifiers when they are numerals less than 4, as these behave differently than the other numeral words (as they are used more, among other reasons). I wonder if this has any implications for the broad use of the Swadesh list, especially in cases like in the ASJP database which only has around 40 words per language in it. Later, he also mentions Corbett (2000), as the Animacy Hierarchy influences the lexicalisation of classifiers in Warekena.

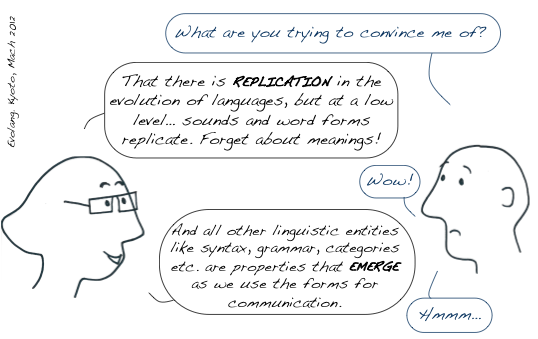

The argument stands on the idea that a cline of grammaticality in current systems may show a hypothetical evolutionary ladder, which Pothipath rightfully notes as tentative thikning. He also gives a counter example from Beijing Mandarin, which only had limited scope. But, in essence, this is another cyclic case for grammaticalisation theory. Overall, it’s good research, and adds a bit more to the puzzle.

——

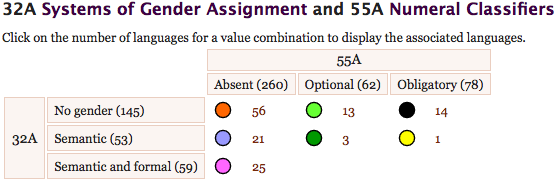

There was at least one open question for me after the talk, which a little WALSing was able to corroborate – is the link between gender assignment and numeral classifiers clear? How do they influence each other? Here’s the WALS markup for that.

As can be seen here, classifiers don’t appear when there is semantic and formal gender assignment. I think that’s interesting. I’d like to take a closer look and see if there are any cases where the numeral classifiers and semantic gender assignments clash – I suspect that they are linked, but that the evolutionary grammaticalisation cycle might be too complex to evolve easily. As I’ve got other evolutionary morphological processes on my mind (cf. my evolang talk), I won’t be looking into this soon, but it is an open question that might have some nice low hanging fruit.

References

- Bowden, J. (2001). Taba: description of a South Halmahera language. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

- Corbett, G. G. (2000). Number. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gil, D. (2005). Numeral classifiers. In M. Haspelmath, M. Dryer, D. Gil & B. Comrie (Eds.), (pp. 226-229).

- Hurford, J.R. (2001) Numeral Systems. In International Encyclopedia of the Social and Behavioral Sciences, edited by N.J.Smelser and P.B.Baltes, Pergamon, Amsterdam. pp.10756- 10761.

- Vipas Pothipath (2008). Typology and Evolution of Numeral-Noun Constructions Unpublished PhD Thesis at the University of Edinburgh

- Pothipath, V. (2011) The Evolution of numeral classifier constructions: a syntax-morphology-lexicon interface.

- Steever, S. B. (1998). Malto in S.B.Steever (ed.) The Dravidian languages. London: Routledge, pp. 359-387.