Culture, its evolution and anything inbetween

You sometimes hear people complaining about the use of the term “language evolution” when what people really mean is historical linguistics, language change or the cultural evolution of language. So what’s the difference?

Some people argue that evolution is a strictly biological phenomenon; how the brain evolved the structures which acquire and create language, and any linguistic change is anything outside of this.

Sometimes this debate gets reduced to the matter of whether there are enough parallels between the cultural evolution of language and biological evolution to justify them both having the “evolution” label. George Walkden recently did a presentation in Manchester on why language change is not language evolution and dedicated quite a large chunk of a presentation to where the analogy between languages and species fall down. It is true that there are a lot of differences between languages and species, and how these things replicate and interact, and of course it is difficult to find them perfectly analogous.

However, focussing on the differences between biological and cultural evolution in language causes one to overlook why a lot of evolutionary linguistics work looks at cultural evolution. Work on cultural evolution is trying to address the same question as studies looking directly at physiology, why is language structured the way it is? Obviously how structure evolved is the main question here, but how much of this was biological, and how much is cultural is still a very open question. And any work which looks at how structure comes about, either through biological or cultural evolution can, in my opinion, legitimately be called evolutionary linguistics.

Additionally, in the absence of direct empirical evidence in language evolution, the indirect evidence that we can gather, either through observing the structure of the world’s languages, or by using artificial learning experiments, can help us answer questions about our cognitive abilities.

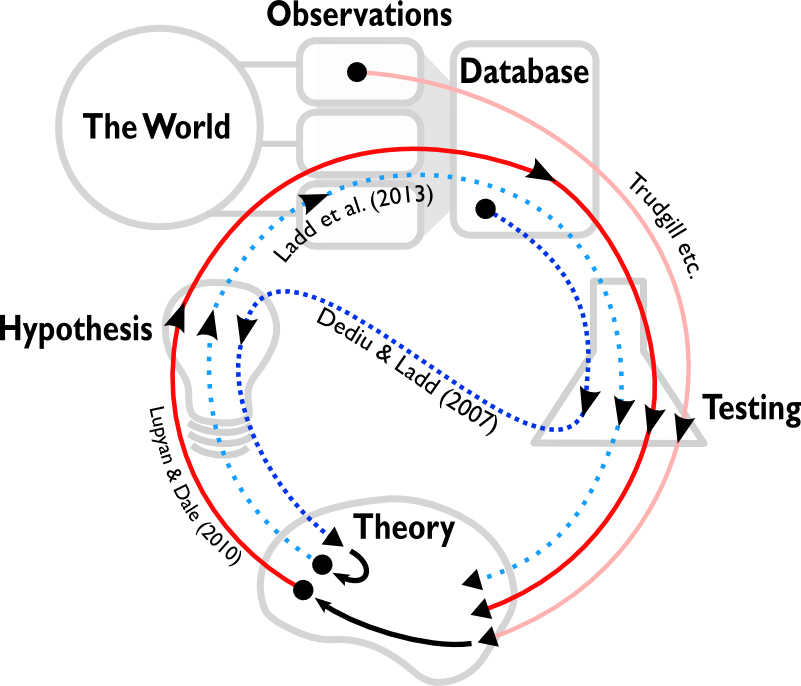

Furthermore, Kirby (2002) outlined 3 timescales of language evolution on the levels of biological evolution (phylogenetic), cultural evolution (glossogentic) and individual development (ontogentic). All of these timescales interact and influence each other, so it’s necessary to consider all of these levels in language evolution research, and to say work on any of these timescales is not language evolution research is not respecting the big picture.

So what’s the difference between language change and language evolution? As with almost everything, it’s not a black and white issue. I would say though that studies looking at universal trends in language, or cultural evolution experiments in the lab, are very relevant to language evolution. What I’d label historical linguistics, or studies on language change, however, is work which presents data from just one language, as it is hard to make inferences about the evolution of our universal capability for language with just one data point.

Figure 1 from: Kirby, S. (2002b). Natural language from artificial life. Artificial Life, 8(2):185-215.

This is a guest post by Joses Ho.

Science fiction has been called “the fiction of ideas”. In this series of blog posts we catalogue a (non-exhaustive) list of works in the genre that explore ideas about language and linguistics.

Science fiction (abbreviated SF amongst devotees) has been called “the fiction of ideas”. And what a pantheon of eye-glazing, heart-palpitating, and brain-melting ideas: time travel, cyborg consciousness, alien invasions. However, does SF go further than mere fictive investigation of cool concepts? Can SF be a fiction of ideas about ideas?

One such idea about ideas, familiar to anyone who paid attention in any introductory undergraduate lecture on linguistics or cognitive science, is linguistic relativity (also popularly known as the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis). Briefly, for the benefit of the rest of us who fell asleep in aforementioned lectures, it conjectures that the language you speak determines and shapes the way you think and the way you perceive “the universe around you” (Star Trek fans will instantly think of the Tamarian language, which can only be understood if you know the cultural references). Below I discuss 3 works that play with this idea.

Our first example of a SF piece that explores linguistic relativity is the novella Story of Your Life by Ted Chiang, first published in 1998, and soon to be adapted into a movie.

An alien race of Heptopods has landed on Earth, and our protagonist and narrator, Louise Banks, is a linguist contacted by the US military to learn their language and communicate with them. As the tale unfolds, Louise’s very view of reality is radically altered as she masters the written language of the Heptopods. Louise tells the reader:

…Even though I’m proficient with [written Heptapod], I know I don’t experience reality the way a heptapod does. My mind was cast in the mould of human languages, and no amount of immersion in an alien language can completely reshape it. My world-view is an amalgam of human and heptapod.

Chiang brilliantly employs an unusual narrative structure to reflect this, and we are given a glimpse into how linguistic relativity might actually work in real time.

This novella is also characteristic of Chiang’s SF work, which consists solely of short stories, written with economic prose and crisp exposition fined-tuned to deliver devastatingly satisfying endings.

Another shorter example is Words And Music by Ronald D. Ferguson. Describing an alien species known as the Utmano, the narrator tells us:

.., Utmano translation doesn’t compare well to translations among human languages. The Utmano language has a peculiar view of tense, you know, past, present, future, in its sentences — well maybe not sentences, but the complete-thought communication structure. Psychologists claim that the Utmano have a lingering, vivid, recent memory combined with a mild prescience that blends with their perception of the ‘now’. It sounds like gobbledegook, but they claim that the Utmano idea of the present spans from the middle of last week to a couple of hours from now.

The above expository paragraph is more typical of how linguistic relativity is explored in SF. While Words and Music doesn’t quite go as far as Chiang does in using the narrative structure itself to illustrate the alien mode of perception being described, Ferguson uses a novel framing device to pack quite a bit of story and exposition into a short space.

Our last selection is novel by celebrated SF writer China Miéville. Embassytown was his ninth novel and features the Ariekei, an alien race whose spoken language involved vocalizing two words simultaneously.

This is not a terribly new idea; Ferguson makes mention of this in Words and Music. In Ferguson’s story, the humans successfully apply the obvious solution (used by real-world linguists in the field as well, and mentioned in Story of Your Life) to the problem of communicating with such an alien race: use pre-recorded or synthetic speech. But Miéville won’t have that.

Synthetic speech is indiscernible to the Ariekei, because they require an actual mind to be uttering each (simultaneous) syllable. And so, the intergalatic human Ambassadors are specially-bred twins whose minds are linked, able to speak with two mouths and one mind. (If that idea doesn’t make your eyes glaze and brain melt, you are probably an Ariekei.)

These Ambassadors are the only ones who can communicate with the Ariekei, and are crucial to human-Ariekei diplomatic and trade relations. The plot gets truly interesting when a new pair of ambassadors arrives to the city of the novel’s title. These two individuals are not genetically identical, but have been selected for linkage based on their high degree of empathy. When they speak the alien language (which Miéville simply christens, a little pompously, “Language”), the effect on the Ariekei is unprecedented: they become addicted to the new Ambassador’s speech.

The rest of the novel runs along on a action-filled plot, and still manages to raise questions about mind, intelligence, and the very nature of language.

However, despite how strange the Ariekei appear, there are cases of human language use that are similar to the way their “Language” functions. Humans actually can speak two things simultaneously, using signed language and spoken language. This is called “code-blending”. Interestingly, the two words they speak and sign simultaneously can refer to different things, or are “semantically non-equivalent.”

An example is given below; the capitalised text on the lower line represents the signs used (taken from Emmorey, Bornstein & Thompson (2005) and Emmorey et al., 2008).

In this picture, a man is describing a scene between the cartoon characters Sylvester the cat and Tweety the bird.

“He” refers to Sylvester who is nonchalantly watching Tweety swinging inside his bird cage on the window sill. Then all of a sudden, Tweety turns around and looks right at Sylvester and screams (“Ack!”). The sign glossed as LOOK-AT-ME is produced at the same time as the English words “all of a sudden.” [The emphasis is mine, and not in the original academic paper.]

The speaker is using both signed language and spoken language to narrate how Tweety suddenly turns to look at Sylvester sneaking up on him. So the simultaneous speech sounds of Miéville’s Ariekei might not be that far off from actual human communication.

This cross-modal flexibility in human communication may suggest that, no matter how intertwined language and thought may be, there may be no language that we truly won’t be able to understand.

We are by no means the only ones to have noticed how linguistics is a well-explored topic in SF. There is an excellent entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction devoted to linguistics as a topic and a trope in science fiction; its exhaustive breadth (it is an encyclopedia article, after all) is remarkable, listing several source texts in a polished tone, although it omits to mention the specific pieces of fiction we have discussed above.

Dr. Maggie Browning, an associate professor in linguistics at Princeton, has compiled a bullet-point list on her website. The book recommendation site Goodreads features as well a crowdsourced list titled “Science Fiction using Languages or Linguistics as a Plot Device”. Both places are invaluable starting points for relevant primary material.

Last, but not least, there is the Alien Tongues blog, written by two graduate students in linguistics, and focussing on the links between SF and linguistics. It has several posts on the constructed languages found in much of SF.

We hope you have enjoyed this post, which we hope this will not be the last on this fascinating topic!

Joses Ho is a currently pursuing a PhD in neuroscience at the University of Oxford, and as a visiting researcher at the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics. His interests also include science fiction, theology, and film. His fiction and poetry have appeared, respectively, in Nature Futures and Quarterly Literary Review Singapore. Follow him on Twitter; his handle is @jacuzzijo.

Professor Russell Gray (University of Auckland, New Zealand) will present his work on the evolution of language, culture and cognition at the annual Nijmegen Lectures in January 2014.

Professor Russell Gray (University of Auckland, New Zealand) will present his work on the evolution of language, culture and cognition at the annual Nijmegen Lectures in January 2014.

In the Nijmegen lectures series, a leading scientist in the fields of psychology or linguistics presents a three-day series of lectures and seminars. The purpose of the series is to allow broad and intensive coverage of research topics by providing extensive interaction among the invited speaker and the participants. The series is a collaborative activity of the Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, the Donders Institute and the Radboud University Nijmegen.

Prof. Gray will present three lectures focussing on language, culture and cognition. A number of top researchers will serve as discussants to the series, including Bart de Boer, Katie Cronin, Harald Hammarström, Ceceila Heyes, Asifa Majid and Monica Tamariz.

Call for posters

The Nijmegen Lectures will include a poster session on topics related to this year’s theme: Evolution of language, culture and cognition. We invite submissions of abstracts for posters, particularly from junior researchers, and especially studies relating to the theme of the lectures.

Please submit an abstract of no more than 300 words by email to sean.roberts@mpi.nl. Please include a title, authors, affiliations and contact email addresses (not included in the word count). The deadline is November 15th, 2013. Abstracts will be moderated by the Nijmegen lectures committee and candidates will be informed of decisions by November 29th.

The poster session will take place on January 28th from 16:30-18:00. We remind candidates that admission to the Nijmegen lectures is free, but registration is required for the afternoon discussion sessions. Please visit http://www.mpi.nl/events/nijmegen-lectures-2014 for more details. We regret that we cannot offer financial support to candidates.

That’s a guest post I’ve contributed to Language Log. The disciplines are literary criticism on the one hand, and computational linguistics on the other. Here’s an abstract:

Though computational linguistics (CL) dates back to the first efforts in machine translation in the mid 1950s, it is only in the last decade or so that it has had a substantial impact on literary studies through the statistical techniques of corpus linguistics and data mining (know as natural language processing, NLP). In this essay I briefly review the history of computational linguistics, from its early days involving symbolic computing to current developments in NLP, and set that in relationship to academic literary study. In particular, I discuss the deeply problematic struggle that literary study has had with the question of evaluation: What makes good literature? I argue that literary studies should own up to this tension and recognize a distinction between ethical criticism, which is explicitly concerned with values, and naturalist criticism, which sidesteps questions of value in favor of understanding how literature works in the mind and in culture. I then argue that the primary relationship between CL and NLP and literary studies should be through naturalist criticism. I conclude by discussing the relative roles of CL and NLP in a large-scale and long-term investigation of romantic love.

Language scientists in Nijmegen have been showing off their artistic side, capturing their research in photography. Head over to Taal in Beeld for a look at the entries – some of them are really stunning.

My entry was a picture of my fieldsite (my computer), made up of 36,864 graphs which show how every linguistic variable in the World Atlas of Language Structures correlates with every other variable. You can see it here. It’s inspired by my work with James Winters on spurious correlations in cultural traits.

I’m a computational linguist who looks at cross-cultural patterns in typology. With increasing amounts of data available for free, correlations are being discovered all the time between unlikely variables: Future tense and economic decisions; altitude and ejective sounds; linguistic gender and political power; linguistic diversity and traffic accidents. There’s a rush to discover interesting correlations, but actually little rigour in how the statistics are controlled.

When looking at the image, it’s tempting to try and find some correlations that look significant and imagine a causal story. However, the text on the screen (taken from artist Nathan Coley’s work “There will be no miracles here“) reminds us that, while we’d like to believe that anyone could make a chance discovery that explains how language works, we must remain rational and keep in mind the bigger picture.

You can download the full image here (22MB). And here’s the R script that made the picture.

The Taal in Beeld exhibition will be on display throughout October in the central hall of the Mariënburg Library in the center of Nijmegen.

James and I have a new paper out in PLOS ONE where we demonstrate a whole host of unexpected correlations between cultural features. These include acacia trees and linguistic tone, morphology and siestas, and traffic accidents and linguistic diversity.

We hope it will be a touchstone for discussing the problems with analysing cross-cultural statistics, and a warning not to take all correlations at face value. It’s becoming increasingly important to understand these issues, both for researchers as more data becomes available, and for the general public as they read more about these kinds of study in the media (e.g. recent coverage in National Geographic, the BBC and TED). But why are the public fascinated with these findings? Here’s my guess:

People are always intrigued by stories of scientific discovery. From Mary Anning‘s discovery of a fossilised ichthyosaur when she was just 12 years old, to Fleming’s accidental production of penicilin to Newton’s apple, it’s tempting to think that anyone could trip over a major breakthrough that is out there just waiting to be found. This is perhaps why there has been so much media interest recently in studies which show surprising statistical links between cultural features such as chocolate consumption and Nobel laureates, future tense and economic decisions, linguistic gender and power or geography and phoneme inventory.

Caleb Everett, who recently discovered a link between altitude and the use of ejective sounds, describes his discovery in these terms:

Everett recalled being shocked by his discovery. “I remember stepping out from my desk and saying, ‘Okay, this is kind of crazy,'” he said. “My first question was, How had we not noticed this?”

That is, we live in an age when there is more data available than ever before, it’s more widely available and there are better tools to do analyses. Anyone with an ordinary laptop and access to the internet could make these discoveries. Indeed, we’ve uncovered many unexpected correlations at Replicated Typo. However, just as Anning’s discoveries were made as the theory of biological evolution was still developing, the ability to detect correlations in cultural features is outstripping the understanding of how to assess these findings. Early reconstructions of fossils included a lot of errors, some of which have been difficult to redress in the public’s mind. Without a good understanding of cultural evolution, similar mistakes might be made during the current race to find statistical links in our field.

Everyone knows that correlation does not imply causation, but there are other problems inherent in studies of cultural features. One problem that is often discounted in these kinds of study is the historical relationship between cultures. Cultural features tend to diffuse in bundles, inflating the apparent links between causally unrelated features. This means that it’s not a good idea to count cultures or languages as independent from each other. Here’s an example: Suppose we look at a group of highschool students and wonder whether the colour of their t-shirts correlates with the kind of food they bring for lunch. We survey 10 children, and see that 5 wear red t-shirts and eat peanut-butter sandwiches. This appears to be strong evidence for a link, but then we see that these 5 pupils come from the same family. There’s now a better explanation for the trend – the children from the same family tend to have the same choice of clothes and are given the same lunch by their parents. The same problem exists for languages. Languages in the same historical families, like English and German, tend to have inherited the same bundles of linguistic features. For this reason, it can be quite complicated to work out whether there really are causal links between cultural properties.

Our paper tries to demonstrate the importance of controlling for this problem by pointing out a chain of statistically significant links, some of which are unlikely to be causal. The diagram below shows the links, those marked with ‘Results’ are links that we’ve discovered and demonstrate in the paper.

For instance, linguistic diversity is correlated with the number of traffic accidents in a country, even controlling for population size, population density, GDP and latitude. While there may be hidden causes, such as state cohesion, it would be a mistake to take this as evidence that linguistic diversity caused traffic accidents.

In the paper we suggest that correlation studies should demonstrate at least two things:

We discuss some methods for achieving this, and demonstrate that they can debunk the spurious correlations that we discover in the first section. Many of these methods are straightforward and can be done quickly, so there’s no excuse for avoiding them.

As well as careful statistical controls, correlation studies can also be assessed based on whether they are motivated by prior theory or not. For example, Lupyan & Dale’s (2010) demonstration of a correlation between population size and morphological complexity was motivated by a long line of research on languages in contact. However, both kinds of discovery can be useful if they are seen in the context of a wider scientific method. We argue that correlation studies should be viewed as explorations of data, and as a sort of feasibility study for further, experimental, research. For example, the chance discovery of a link between genes and tone by Dediu & Ladd was not only statistically well controlled, but was used as the inspiration for more detailed laboratory experiments, rather than being seen as proof in itself.

Coming across statistical patterns by chance has always been part of the scientific process. However, with culture, it’s much more difficult to intuitively distinguish real patterns from noise or historical influence. Correlations between unexpected features will continue to be exciting, but researchers should apply the right controls and see the studies as motivational rather than direct tests of hypotheses.

Roberts, S. & Winters, J. (2013). Linguistic Diversity and Traffic Accidents: Lessons from Statistical Studies of Cultural Traits. PLOS ONE, 8 (8) e70902 : doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0070902

An Essay in Cognitive Rhetoric

I want to step back from the main thread of discussion and look at something else: the discussion itself. Or, at any rate, at Dennett’s side of the argument. I’m interested in how he thinks and, by extension, in how conventional meme theorists think.

And so we must ask: Just how does thinking work, anyhow? What is the language of thought? Complicated matters indeed. For better or worse, I’m going to have to make it quick and dirty.

Embodied Cognition

In one approach the mind’s basic idiom is some form of logical calculus, so-called mentalese. While some aspects of thought may be like that, I do not think it is basic. I favor a view called embodied cognition:

Cognition is embodied when it is deeply dependent upon features of the physical body of an agent, that is, when aspects of the agent’s body beyond the brain play a significant causal or physically constitutive role in cognitive processing.

In general, dominant views in the philosophy of mind and cognitive science have considered the body as peripheral to understanding the nature of mind and cognition. Proponents of embodied cognitive science view this as a serious mistake. Sometimes the nature of the dependence of cognition on the body is quite unexpected, and suggests new ways of conceptualizing and exploring the mechanics of cognitive processing.

One aspect of cognition is that we think in image schemas, simple prelinguistic structures of experience. One such image schema is that of a container: Things can be in a container, or outside a container; something can move from one container to another; it is even possible for one container to contain another.

Memes in Containers

The container scheme seems fundamental to Dennett’s thought about cultural evolution. He sees memes as little things that are contained in a larger thing, the brain; and these little things, these memes, move from one brain to another.

This much is evident on the most superficial reading of what he says, e.g. “such classic memes as songs, poems and recipes depended on their winning the competition for residence in human brains” (from New Replicators, The). While the notion of residence may be somewhat metaphorical, the locating of memes IN brains is not; it is literal.

What I’m suggesting is that this containment is more than just a contingent fact about memes. That would suggest that Dennett has, on the one hand, arrived at some concept of memes and, on the other hand, observed that those memes just happen to exist in brains. Yes, somewhere Over There we have this notion of memes as the genetic element of culture; that’s what memes do. But Dennett didn’t first examine cultural process to see how they work. As I will argue below, like Dawkins he adopted the notion by analogy with biology and, along with it, the physical relationship between genes and organisms. The container schema is thus foundational to the meme concept and dictates Dennett’s treatment of examples.

The rather different conception of memes that I have been arguing in these notes is simply unthinkable in those terms. If memes are (culturally active) properties of objects and processes in the external world, then they simply cannot be contained in brains. A thought process based on the container schema cannot deal with memes as I have been conceiving them. Continue reading “Turtles All the Way Down: How Dennett Thinks”

Having now clearly established memes as properties of objects and events in the external world, properties that provide crucial data for the operation of mental “machines,” I want to step aside from thinking about memes and cultural evolution as such and think a bit about the mind. I want to set this conversation up by, once again, quoting from Dennett’s recent interview, The Well-Tempered Mind, at The Edge:

The question is, what happens to your ideas about computational architecture when you think of individual neurons not as dutiful slaves or as simple machines but as agents that have to be kept in line and that have to be properly rewarded and that can form coalitions and cabals and organizations and alliances? This vision of the brain as a sort of social arena of politically warring forces seems like sort of an amusing fantasy at first, but is now becoming something that I take more and more seriously, and it’s fed by a lot of different currents.

A bit later:

It’s going to be a connectionist network. Although we know many of the talents of connectionist networks, how do you knit them together into one big fabric that can do all the things minds do? Who’s in charge? What kind of control system? Control is the real key, and you begin to realize that control in brains is very different from control in computers. Control in your commercial computer is very much a carefully designed top-down thing.

That’s the problem David Hays and I set ourselves in Principles and Development of Natural Intelligence (Journal of Social and Biological Systems 11, 293 – 322, 1988). While we had something to say about control in our discussion of the modal principle, we addressed the broader question of how to construct a mind from neurons that aren’t simple logical switches.

It is by no means clear to me how Dennett, and others of his mind-set, think about the mind. Yes, it’s computational. I can deal with that. But not, as I’ve said, if it’s taken to mean that the primitive operations of the nervous system are like the operations in digital computers, not if it’s taken to imply that the mind is constituted by ‘programs’ written in the ‘mentalese’ version of Fortran, Lisp, or C++. THAT was never a very plausible idea and the more we’ve come to know about the nervous system, the less plausible it becomes.

The upshot is that we need a much more fluid, a much more dynamic, conception of the mind. In Beethoven’s Anvil I talked of neural weather. Here’s how I set-up that metaphor (pp. 71-72): Continue reading “The Mind is What the Brain Does, and Very Strange”

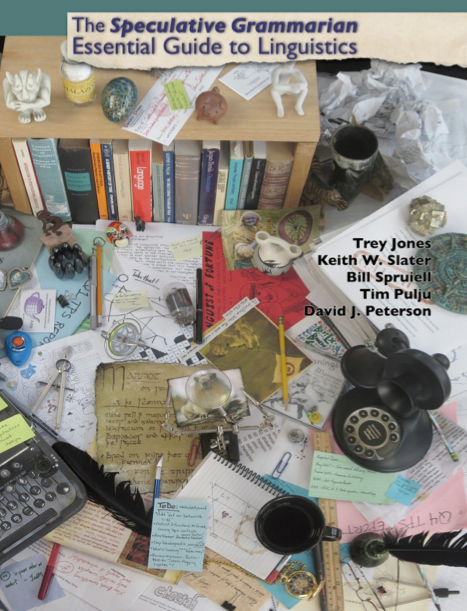

What does a Labio-nasal sound like? What is the laziest language on earth? How can a knowledge of linguistics help make macaroni cheese? What is the tiny phoneme hypothesis? Where can you find a book that synergises all the loose ends of linguistics into a unified, transparent theory? I don’t know. In the meanwhile, try reading the Speculative Grammarian Essential Guide to Linguistics.

Many of you will know and fear the Speculative Grammarian journal, the ultimate Shibboleth in the field of languaging (and if you know what a Shibboleth is, and are proud of it, then this might be for you). Now the best cuttings have been complied into a book which takes you on a quiestionable journey right accross the field from phonetics to sociolinguistics in a quest to make linguistics look as bonkers as a real science like quantum physics.

Many of you will know and fear the Speculative Grammarian journal, the ultimate Shibboleth in the field of languaging (and if you know what a Shibboleth is, and are proud of it, then this might be for you). Now the best cuttings have been complied into a book which takes you on a quiestionable journey right accross the field from phonetics to sociolinguistics in a quest to make linguistics look as bonkers as a real science like quantum physics.

You’ll learn about the linguistic uncertainty principle (it’s impossible to simultaneously know both the synchronic state of a language and the direction of its drift). You’ll revel in the poetry of Yune O. Hūū, II. You’ll understand exactly which part of ‘no’ you don’t understand. You’ll wonder about granular phonology. In fact, you’ll wonder about a lot of things, like how this got published. It even includes the finding that started the whole spurious correlation saga, the role of the Acacia tree in language evolution.

Complete with a choose-your-own-career-in-linguistics adventure game (German-sign-language-shaped dice not included), this is the ultimate gift for the budding language student, the jaded academic or the holistic forensic linguist. And just in time for Christmas.

You can buy the book at the SpecGram website.

Dubious praise:

“Ever wonder why Vikings torched scriptoria? This kind of thing.”

—E. V. Gordon

“Funnier than any other book I’ve read in the entire 20th Century!”

—Rasmus Rask

“Contains more than 100 basic words.”

—Morris Swadesh

“Same reference as linguistics; different sense.”

—Gottlob Frege

“Most of the changes I would make are, of course, to remove commas.”

—An Anonymous Proofreader

“This book is so chock full of borrowings and analogy that it is utterly unsuited to any sort of scholarly discourse.”

—Neogrammarian Quarterly

“Two uvulas down, way down!”

—Sapir and Bloomfield, At the Bookstore