It’s time I get back to my attempt to lay out a map of approaches to cultural evolution in a limited number of posts, say a half dozen or even less (in my first post I said three). This is the first of two or three posts in which I look at ideas of the microscale entities and processes. In this post I’ll take a close look at Dawkins’ concept of the meme as he laid it out in The Selfish Gene. In my next post or two I’ll lay out other positions while developing mine in the process.

Dawkins Defines the Meme

I’m going to take a close look at two paragraphs from the 30th Anniversary edition of The Selfish Gene (Oxford 2006). First I’ll quote the paragraphs without interruption and commentary. Then I’ll repeat them, this time inserting my own comments after passages from Dawkins.

The book, of course, is not primarily about culture. It is about biology and argues a gene-centric view of evolution. In the process Dawkins abstracts from the biology and extracts two roles, that of replicator and that of vehicle. Genes play the replicator role and phenotypes play vehicle role. From a gene-centric point of view, the function of phenotypes is to carry genes from one generation to the next.

Have set this out in ten chapters, Dawkins then turns to culture in the eleventh chapter, where he introduces the meme in the replicator role in cultural evolution. The paragraphs we’re examining are on pages 192-193:

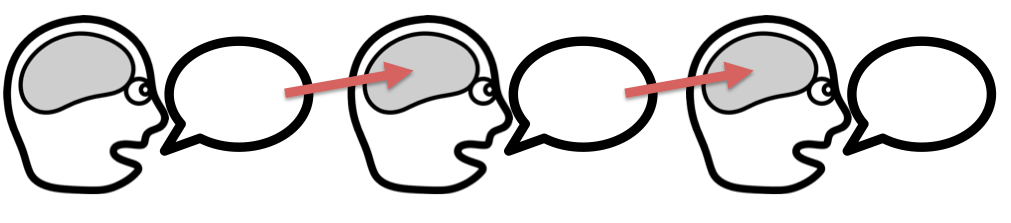

Examples of memes are tunes, ideas, catch-phrases, clothes fashions, ways of making pots or of building arches. Just as genes propagate themselves in the gene pool by leaping from body to body via sperms or eggs, so memes propagate themselves in the meme pool by leaping from brain to brain via a process which, in the broad sense, can be called imitation. If a scientist hears, or reads about, a good idea, he passes it on to his colleagues and students. He mentions it in his articles and his lectures. If the idea catches on, it can be said to propagate itself, spreading from brain to brain. As my colleague N. K. Humphrey neatly summed up an earlier draft of this chapter:’… memes should be regarded as living structures, not just metaphorically but technically. When you plant a fertile meme in my mind you literally parasitize my brain, turning it into a vehicle for the meme’s propagation in just the way that a virus may parasitize the genetic mechanism of a host cell. And this isn’t just a way of talking—the meme for, say, “belief in life after death” is actually realized physically, millions of times over, as a structure in the nervous systems of individual men the world over.’

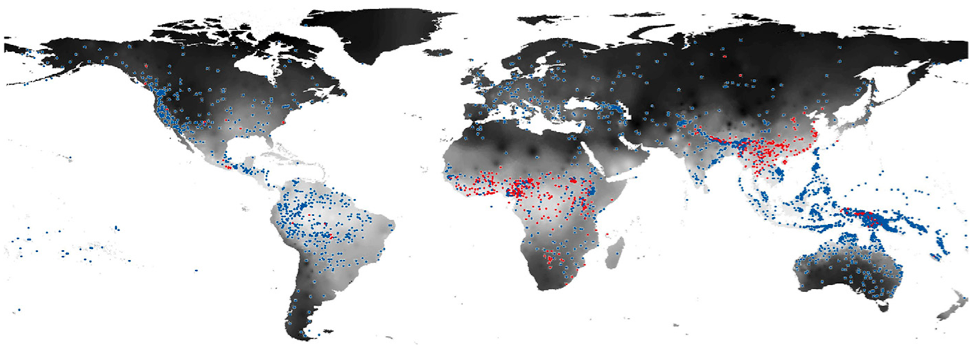

Consider the idea of God. We do not know how it arose in the meme pool. Probably it originated many times by independent ‘mutation’. In any case, it is very old indeed. How does it replicate itself? By the spoken and written word, aided by great music and great art. Why does it have such high survival value? Remember that ‘survival value’ here does not mean value for a gene in a gene pool, but value for a meme in a meme pool. The question really means: What is it about the idea of a god that gives it its stability and penetrance in the cultural environment? The survival value of the god meme in the meme pool results from its great psychological appeal. It provides a superficially plausible answer to deep and troubling questions about existence. It suggests that injustices in this world may be rectified in the next. The ‘everlasting arms’ hold out a cushion against our own inadequacies which, like a doctor’s placebo, is none the less effective for being imaginary. These are some of the reasons why the idea of God is copied so readily by successive generations of individual brains. God exists, if only in the form of a meme with high survival value, or infective power, in the environment provided by human culture.

Dawkins says more about memes (the chapter runs from 189 to 201), but I’ll confine my commentary to those two chapters. Before I do that, however, I’d like to quote two short paragraphs from the end of the chapter (pp. 199-200):

However speculative my development of the theory of memes may be, there is one serious point which I would like to emphasize once again. This is that when we look at the evolution of cultural traits and at their survival value, we must be clear whose survival we are talking about. Biologists, as we have seen, are accustomed to looking for advantages at the gene level (or the individual, the group, or the species level according to taste). What we have not previously considered is that a cultural trait may have evolved in the way that it has, simply because it is advantageous to itself.

We do not have to look for conventional biological survival values of traits like religion, music, and ritual dancing, though these may also be present. Once the genes have provided their survival machines with brains that are capable of rapid imitation, the memes will automatically take over. We do not even have to posit a genetic advantage in imitation, though that would certainly help. All that is necessary is that the brain should be capable of imitation: memes will then evolve that exploit the capability to the full.

That I believe is the core of Dawkins’ contribution, that the entity that directly benefits from cultural evolution is some cultural entity, not any individual human being, though the cultural entity is necessarily dependent on individual humans for its existence. Continue reading “Issues in Cultural Evolution 2.1: Micro Evolution, Dawkins and Memes”