Broadly considered, description is how phenomena are brought into intellectual discourse. Such discourse is thereby bounded by the scope of the descriptive powers at its disposal. What descriptive techniques are at the disposal of the literary critic?

The question is a real one, and has real answers, but I ask it rhetorically. Whatever those techniques are, diagrams do not figure prominently in them. One can read pages and pages and pages of first class literary criticism and never encounter a diagram.

The argument of this essay is that we’ve gone as far as we can go down those various paths. If we are to create a new literary criticism for this new millennium, then we must have some new conceptual tools, and some of those must be visual. The diagrams I imagine, not to mention the diagrams I have been doing for the last four decades, are tools to think with. They are not mere aids to thought, they are the substance of thought itself. Not all thought, of course, but some thought.

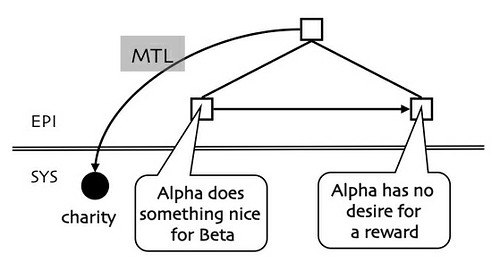

These diagrams are descriptive tools. Some describe texts and textual phenomena, while others describe the mental machinery underlying texts. The distinction is critical, and will occupy much of this essay.

* * * * *

Diagrams of various kinds are central to objectification, which we can consider a particular mode of description. The aim of objectification is to make a sharp distinction – as sharp as possible – between the things we are talking about, aka the objects under discussion, and our means of talking about them.

As my principal concern is with naturalist literary criticism, I have to consider the difficulties of talking about language. On the one hand, we do it all the time. Recall that in Jakobson’s well-known characterization of the speech situation metalingually is one of the functions of language. But such usage is casual and does not aim at understanding of language itself.

Nor, for that matter, does literary analysis aim at understanding language itself. Yes, it aims at the understanding of language, as literature is in part constructed of language. That is the most ‘visible’ aspect of the literary work, it’s ‘skin’ so to speak. But works of literary art are also constructed of feelings, perceptions, ideas, emotions, desires, dreams, and so forth, none completely assimilable by language. We must be as clear as possible in our descriptions so that we may be in a position better to keep track of what we’re talking about.

I begin by outlining the ambiguous states the concept of the “text” has within literary criticism, though I don’t come anywhere near the idea that all the world is a text, which is slipped in under the far reaches of the ambiguity I look at. From there I offer a few words about scientific description, ending with the characterization of the shape of the DNA molecule. From there I go to literary description, the text proper, and the description of conceptual structures, mental machinery behind the text.

The Ambiguity of “Text”

What do literary critics mean when we refer to “the text”? there are times, of course, when we mean the physical thing, whether written or spoken, e.g. when analyzing the a poem’s rhyme scheme. But generally we mean to indicate something more diffuse, something anchored in that physical text, those marks on paper or waves in the air, but going beyond them. Just what that “something more” is, that’s not so clear.

Thus, as used in literary critical discourse, the concept of the text is ambiguous as between the physical signifiers and the signifieds, the concepts linked to those signifiers via linguistic convention. When we talk about the text, we generally mean to include the ordinary process of reading exclusive of any secondary exegesis or explication.

Within computational linguistics, however, there is a sharp distinction between the physical sign, whether written or oral, and the literary critic’s text, as I’ve defined it above. Optical character recognition (OCR) takes a written text as input and produces a machine-readable text as output. OCR software works very well for typed and typeset text; errors will be made, but they are relatively few. OCR software works poorly for text written in cursive script. Whatever the source text, OCR software makes no attempt to “understand” the text, but text understanding – in some sense of the word – is of enormous interest and practical value. It is also very difficult to do, and I’m talking about text understanding merely at the literal level. Feed the computer a news story about, say, the recent typhoon in the Philippines and ask it simple questions: What city was hit hardest? How many people have died so far? That’s simple basic stuff, for a human. Not so simple for a computer, though still basic.

When I get to talking about ways of describing literary texts I will be interested in techniques that are sensitive to the distinction between the physical texts, the signifiers, and the process of understanding the meaning of those signifiers at the most basic level, the level without which more sophisticated understanding – if such is called for – is not possible. Continue reading “Description Redux, Again: On the Methodological Centrality of Diagrams”