I just finished watching the latest episode of Horizon, Is seeing believing? It had lots of cool material on recent research into our perceptual systems and how some unique individuals (see bat man and synaesthesia) are providing clues into the degree of plasticity our brain is capable of. I think this developmental flexibility has important implications for how we view the evolution of language, which certainly chimes with Deacon’s latest explanations. Another segment of the episode focused on a famous linguistic perceptual trick, known as the McGurk effect, demonstrating the interaction between hearing and vision in speech perception. Here is the first video I found on the subject (although I thought the Horizon episode provided a better visual explanation of it):

Category: Science

Regularities in Cultural Evolution

I recently came across a post over at GNXP on the rise and crash of civilizations. It’s a really interesting discussion on a new paper by Currie et al. (2010), Rise and fall of political complexity in island South-East Asia and the Pacific. Here is the abstract:

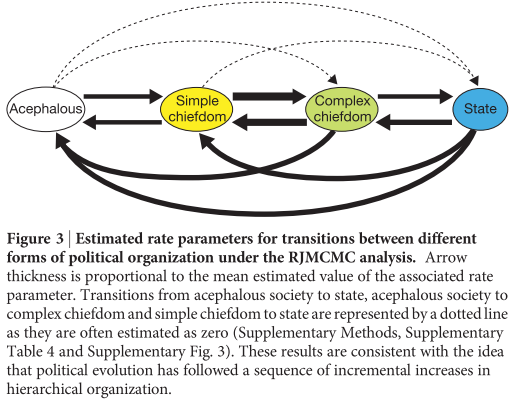

There is disagreement about whether human political evolution has proceeded through a sequence of incremental increases in complexity, or whether larger, non-sequential increases have occurred. The extent to which societies have decreased in complexity is also unclear. These debates have continued largely in the absence of rigorous, quantitative tests. We evaluated six competing models of political evolution in Austronesian-speaking societies using phylogenetic methods. Here we show that in the best-fitting model political complexity rises and falls in a sequence of small steps. This is closely followed by another model in which increases are sequential but decreases can be either sequential or in bigger drops. The results indicate that large, non-sequential jumps in political complexity have not occurred during the evolutionary history of these societies. This suggests that, despite the numerous contingent pathways of human history, there are regularities in cultural evolution that can be detected using computational phylogenetic methods. [My emphasis].

I don’t have much to add on the subject as I think Razib covered most of the relevant points, plus I haven’t even finished reading the paper yet (I’m hoping to get back into research blogging later this week). I will, however, post one of their figures that shows the dynamic between the rise and fall of political complexity, and how it shows regularity (btw, RJMCMC means Bayesian reversible-jump Markov chain Monte Carlo… if that helps you in any way):

Musings of a Palaeolinguist

Hannah recently directed me towards a new language evolution blog: Musings of a Palaeolinguist. From my reading of the blog, the general flavour seems to be focused on gradualist and abruptist accounts of language evolution. Here is a section from one of her posts, Evolution of Language and the evolution of syntax: Same debate, same solution?, which also touches on the protolanguage concept:

In my thesis, I went through a literature review of gradual and abruptist arguments for language evolution, and posited an intermediate stage of syntactic complexity where a language might have only one level of embedding in its grammar. It’s a shaky and underdeveloped example of an intermediate stage of language, and requires a lot of exploration; but my reason for positing it in the first place is that I think we need to think of the evolution of syntax the way many researchers are seeing the evolution of language as a whole, not as a monolithic thing that evolved in one fell swoop as a consequence of a genetic mutation, but as a series of steps in increasing complexity.

Derek Bickerton, one of my favourite authors of evolutionary linguistics material, has written a number of excellent books and papers on the subject. But he also argues that language likely experienced a jump from a syntax-less protolanguage to a fully modern version of complex syntax seen in languages today. To me that seems unintuitive. Children learn syntax in steps, and non-human species seem to only be able to grasp simple syntax. Does this not suggest that it’s possible to have a stable stage of intermediate syntax?

I’ve generally avoided writing about these early stages of language, largely because I had little useful to say on the topic, but I’ve now got some semi-developed thoughts that I’ll share in another post. In regards to the above quote, I do agree with the author’s assertion of there being an intermediate stage, rather than Bickerton’s proposed jump. In fact, we see languages today (polysynthetic) where there are limitations on the level of embedding, with one example being Bininj Gun-wok. We can also stretch the discussion to look at recursion in languages, as Evans and Levinson (2009) demonstrate:

In discussions of the infinitude of language, it is normally assumed that once the possibility of embedding to one level has been demonstrated, iterated recursion can then go on to generate an infinite number of levels, subject only to memory limitations. And it was arguments from the need to generate an indefinite number of embeddings that were crucial in demonstrating the inadequacy of finite state grammars. But, as Kayardild shows, the step from one-level recursion to unbounded recursion cannot be assumed, and once recursion is quarantined to one level of nesting it is always possible to use a more limited type of grammar, such as finite state grammar, to generate it.

The 20th Anniversary of Steven Pinker & Paul Bloom: Natural Language and Natural Selection (1990)

“a post on Pinker and Bloom’s original paper, and how the field has developed over these last twenty years, at some point in the next couple of weeks,”

Language and Thought: Joshua Knobe speaks to Lera Boroditsky

Bloggingheads.tv hosts an interesting conversation between experimental philosopher Joshua Knobe and psychologist/linguist Lera Boroditsky (you should know who she is by now). It’s mostly going over the work of Boroditsky, although I thought Knobe did a good job of asking the right questions and taking a back seat when needed:

Some Links #19: The Reality of a Universal Language Faculty?

I noticed it’s almost been a month since I last posted some links. What this means is that many of the links I planned on posting are terribly out of date and these last few days I haven’t really had the time to keep abreast of the latest developments in the blogosphere (new course + presentation at Edinburgh + current cold = a lethargic Wintz). I’m hoping next week will be a bit nicer to me.

The reality of a universal language faculty? Melodye offers up a thorough post on the whole Universal Grammar hypothesis, mostly drawing from the BBS issue dedicated Evans & Levinson (2009)’s paper on the myth of language universals, and why it is a weak position to take. Key paragraph:

When we get to language, then, it need not be surprising that many human languages have evolved similar means of efficiently communicating information. From an evolutionary perspective, this would simply suggest that various languages have, over time, ‘converged’ on many of the same solutions. This is made even more plausible by the fact that every competent human speaker, regardless of language spoken, shares roughly the same physical and cognitive machinery, which dictates a shared set of drives, instincts, and sensory faculties, and a certain range of temperaments, response-patterns, learning facilities and so on. In large part, we also share fairly similar environments — indeed, the languages that linguists have found hardest to document are typically those of societies at the farthest remove from our own (take the Piraha as a case in point).

My own position on the matter is fairly straightforward enough: I don’t think the UG perspective is useful. One attempt by Pinker and Bloom (1990) argued that this language module, in all its apparent complexity, could not have arisen by any other means than via natural selection – as did the eye and many other complex biological systems. Whilst I agree with the sentiment that natural selection, and more broadly, evolution, is a vital tool in discerning the origins of language, I think Pinker & Bloom initially overlooked the significance of cultural evolutionary and developmental processes. If anything, I think the debate surrounding UG has held back the field in some instances, even if some of the more intellectually vibrant research emerged as a product of arguing against its existence. This is not to say I don’t think our capacity for language has been honed via natural selection. It was probably a very powerful pressure in shaping the evolutionary trajectory of our cognitive capacities. What you won’t find, however, is a strongly constrained language acquisition device dedicated to the processing of arbitrary, domain-specific linguistic properties, such as X-bar theory and case marking.

Babel’s Dawn Turns Four. In the two and half years I’ve been reading Babel’s Dawn it has served as a port for informative articles, some fascinating ideas and, lest we forget, some great writing on the evolution of language. Edmund Blair Bolles highlights the blog’s fourth anniversary by referring to another, very important, birthday:

This blog’s fourth anniversary has rolled around. More notably, the 20th anniversary of Steven Pinker and Paul Bloom‘s famous paper, “Natural Language and Natural Selection,” seems to be upon us. Like it or quarrel with it, Pinker-Bloom broke the dam that had barricaded serious inquiry since 1866 when the Paris Linguistic Society banned all papers on language’s beginnings. The Journal of Evolutionary Psychology is marking the Pinker-Bloom anniversary by devoting its December issue to the evolution of language. The introductory editorial, by Thomas Scott-Phillips, summarizes language origins in terms of interest to the evolutionary psychologist, making the editorial a handy guide to the differences between evolutionary psychology and evolutionary linguistics.

Hopefully I’ll have a post on Pinker and Bloom’s original paper, and how the field has developed over these last twenty years, at some point in the next couple of weeks. I think it’s historical importance will, to echo Bolles, be its value in opening up the field: with the questions of language origins and evolution turning into something worthy of serious intellectual investigation.

Other Links

Hypnosis reaches the parts brain scans and neurosurgery cannot.

Are Humans Still Evolving? (Part Two is here).

On Language — Learning Language in Chunks.

What can Hungarian Postpositions tell us about Language Evolution?

I spent quite a lot of time as an undergraduate analysing Hungarian syntax with my generative head on and using the minimalist framework. Bear with me. This post is the result of me trying to marry all of them hours spent reading “The Minimalist Program” (Chomsky, 1995) and starring at Hungarian with what I’m currently doing¹ and ultimately trying to convince myself that I wasn’t wasting time.

So here’s a condensed summary of what my dissertation was about:

Hungarian has a massive case system which, as well as structural cases, has many items which have locational, instrumental and relational uses (lexical case markers). Because of this many constructions which feature prepositions in English, when translated into Hungarian can be translated as case markers or postpositions.

It struck me as odd that these 2 things; case markers and postpositions, despite having the same position in the structure (as a right-headed modifier to the noun) and very similar semantic function, would have different analyses in the syntactic framework, simply due to the fact that one was morphologically attached (case markers) and the other not (postpositions).

Continue reading “What can Hungarian Postpositions tell us about Language Evolution?”

Matt Ridley’s contractual silence

This morning I just received my copy of Matt Ridley’s latest book, The Rational Optimist: How prosperity evolves. I must admit that, despite being a big fan of Ridley’s writings, I found myself somewhat disillusioned since his role in the subprime mortgage crisis at Northern Rock. In particular, I was always confused as to why Ridley never defended himself against scathing attacks from the likes of George Monbiot. Maybe it was an admission of guilt? Perhaps. But I now have a somewhat more satisfying explanation for the silence:

I am writing in times of unprecedented economic pessimism. The world banking system has lurched to the brink of collapse; an enormous bubble of debt has burst; world trade has contracted; unemployment is rising sharply all around the world as output falls. The immediate future looks bleak indeed, and some governments are planning further enormous public debt expansions that could hurt the next generation’s ability to prosper. To my intense regret I played a part in one phase of this disaster as non-executive chairman of Northern Rock, one of many banks that ran short of liquidity during the crisis. This is not a book about that experience (under terms of my employment there I am not at liberty to write about it). [my emphasis].

So there you have it: a contractual obligation to keep schtum. It’s a shame, really, as I would hate to be in a position where I am not even given the opportunity to defend my position, especially on a topic that generated a massive amount of news and speculation.

As for the book: so far, so good. It’s also a lot larger than I expected. I do have some minor quibbles, but they can wait until I write a more thorough review.

New Language and Genetics department

Next week, on the 1st October, there will be a new language and genetics department opening at the Max Planck Institute, the first research department in the world entirely devoted to understanding the relationship between language and genes!!!

This excites me so I wanted to share the news.

This statement is from Simon Fisher, who will head the new department about what they will be trying to achieve:

‘We aim to uncover the DNA variations which ultimately affect different facets of our communicative abilities, not only in children with language-related disorders but also in the general population, and even through to people with exceptional linguistic skills’, says L&G director Simon Fisher. ‘Our work attempts to bridge the gaps between genes, brains, speech and language, by integrating molecular findings with data from other levels of analysis, particularly cell biology and neuro-imaging. In addition, we hope to trace the evolutionary history and worldwide diversity of the key genes, which may shed new light on language origins.’

More signs of the growing and diversifying field of language evolution!

Here’s a link to the news on the MPI website: http://www.mpi.nl/news/new-mpi-department-language-genetics

Language, Thought, and Space (V): Comparing Different Species

![]() As I’ve talked about in my last posts (see I, II, III, and IV) different cultures employ different coordinate systems or Frames of References (FoR) when talking about space. FoRs

As I’ve talked about in my last posts (see I, II, III, and IV) different cultures employ different coordinate systems or Frames of References (FoR) when talking about space. FoRs

“serve to specify the directional relationships between objects in space, in reference to a shared referential anchor” (Haun et al. 2006: 17568)

As shown in my last post these linguistic differences seem to reflect certain cognitive differences:

Whether speakers mainly use a relative, ego-based FoR, a cardinal-direction/or landmark-based absolute FoR, or an object-based, intrinsic based FoR, also influences how they solve and conceptualise spatial tasks.

In my last post I also posed the question whether there is a cognitive “default setting” that we and the other great apes inherited from our last common ancestor that is only later overridden by cultural factors. The crucial question then is which Frame of Reference might be the default one.

Continue reading “Language, Thought, and Space (V): Comparing Different Species”