Published online at Plos one yesterday a study done at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center by Campbell and de Waal (2011) has found a link between social groups and empathy in chimpanzees as demonstrated by involuntary yawning responses.

Published online at Plos one yesterday a study done at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center by Campbell and de Waal (2011) has found a link between social groups and empathy in chimpanzees as demonstrated by involuntary yawning responses.

The study is based on the psychological concept of ingroups and outgroups. In humans ingroups are those we see as similar to ourselves and outgroups are those we perceive as different.

Biases involved in ingroup-outgroup discrimination in know to even extend to involuntary responses which includes empathy for pain. This has never been tested in other animals though.

Contagious yawning is thought to be linked with empathy. The study used this assumption to test if chimpanzees’ ingroup-outgroup biases would effect how contagious a yawn can be. In other words if contagious yawning is linking to empathy and empathy is linked to ingroup-outgroup biases within chimpanzees then the chimpanzees should yawn more in response to watching ingroup members yawn than outgroup.

The study used 23 chimpanzees from two separate groups and they were made to watch videos of familiar and unfamiliar individuals yawning. Videos of the same chimps not yawning were also used for control. The chimpanzees yawned more when watching the familiar yawns than the familiar control or the unfamiliar yawns, demonstrating an ingroup-outgroup bias in contagious yawning.

The authors have suggested that these result may be more magnified in chimpanzees than it is in humans as chimpanzees live in much smaller communities than humans and are generally very hostile to those outside of their small social group. Ingroup-outgroup biases are therefore probably much more absolute in chimpanzees.

This study adds empirical evidence to suggest that contagious yawning is subject to empathy. This may have further implications for studying the evolutionary foundations of empathy which obviously has implications for things like theory of mind which is pretty high up on the list for preadaptations for language.

References

Campbell MW, de Waal FBM (2011) Ingroup-Outgroup Bias in Contagious Yawning by Chimpanzees Supports Link to Empathy. PLoS ONE 6(4): e18283. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0018283

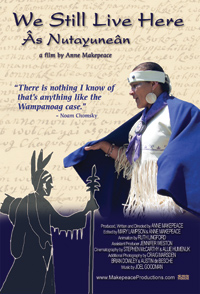

The story begins in 1994 when Jessie Little Doe, an intrepid, thirty-something Wampanoag social worker, began having recurring dreams: familiar-looking people from another time addressing her in an incomprehensible language. Jessie was perplexed and a little annoyed– why couldn’t they speak English? Later, she realized they were speaking Wampanoag, a language no one had used for more than a century. These events

The story begins in 1994 when Jessie Little Doe, an intrepid, thirty-something Wampanoag social worker, began having recurring dreams: familiar-looking people from another time addressing her in an incomprehensible language. Jessie was perplexed and a little annoyed– why couldn’t they speak English? Later, she realized they were speaking Wampanoag, a language no one had used for more than a century. These events New footage has been filmed of a little known animal called the Streaked Tenrec in Madagascar. The footage shows the creatures can rub their quills together to make ultrasound calls and can also produce tongue clicks to each other which are outside of the range of human hearing. Because of the ultra sonic nature of these sounds, it has been unknown quite to the extent that these creatures can do this, before now.

New footage has been filmed of a little known animal called the Streaked Tenrec in Madagascar. The footage shows the creatures can rub their quills together to make ultrasound calls and can also produce tongue clicks to each other which are outside of the range of human hearing. Because of the ultra sonic nature of these sounds, it has been unknown quite to the extent that these creatures can do this, before now. New fossil evidence from Hadar, Ethiopia suggests that our ancestors from 3.2 million years ago (Australopithecus afarensis (better known as Lucy)) had arches in their feet.

New fossil evidence from Hadar, Ethiopia suggests that our ancestors from 3.2 million years ago (Australopithecus afarensis (better known as Lucy)) had arches in their feet.