A new paper in Nature, by Apicella, Marlowe, Fowler & Christakis, was published today. It hypothesises that social network structure may have been present in early human history, and this structure may account for the emergence of cooperation. The study used data from the Haza people of Tanzania, who presumably already have cooperation, so I’m not sure what data they’re using to back up claims of emergence. I can’t read the article because I don’t have institutional access any more, so I’d be keen to hear thoughts others have.

Here’s the abstract:

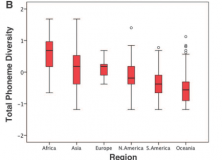

Social networks show striking structural regularities, and both theory and evidence suggest that networks may have facilitated the development of large-scale cooperation in humans. Here, we characterize the social networks of the Hadza, a population of hunter-gatherers in Tanzania. We show that Hadza networks have important properties also seen in modernized social networks, including a skewed degree distribution, degree assortativity, transitivity, reciprocity, geographic decay and homophily. We demonstrate that Hadza camps exhibit high between-group and low within-group variation in public goods game donations. Network ties are also more likely between people who give the same amount, and the similarity in cooperative behaviour extends up to two degrees of separation. Social distance appears to be as important as genetic relatedness and physical proximity in explaining assortativity in cooperation. Our results suggest that certain elements of social network structure may have been present at an early point in human history. Also, early humans may have formed ties with both kin and non-kin, based in part on their tendency to cooperate. Social networks may thus have contributed to the emergence of cooperation.