As soon as I finished up my series of posts about Matt Jockers, Macroanalysis: Digital Methods & Literary History, I set up a file on my Mac for further thoughts, knowing full well I’d keep thinking about the book. I’ve now posted the first of those continuing thoughts at 3 Quarks Daily: Macroanalysis and the Directional Evolution of Nineteenth Century English-Language Novels.

The issue is cultural evolution, a notion that Jockers flirts with, but rejects. Of course I’ve been committed to the idea for a long time and I’ve decided that his data, that is, the patterns he’s found in his data, constitute a very strong argument of conceptualizing literary history as an evolutionary phenomenon. That’s what my 3QD post is about, a fairly detailed (a handful of new visualizations) reanalysis of Jockers’ account of literary influence.

From Influence to Evolution

It is one thing to track influence among a handful of texts; that is the ordinary business of traditional literary history. You read the texts, look for similar passages and motifs, read correspondence and diaries by the authors, and so forth, and arrive at judgements about how the author of some later text was influenced by authors of earlier texts. It’s not practical to do that for over 3000 texts, most of which you’ve never read, nor has anyone read many or even most them in over 100 years. Optimize your HR processes with top peo employment services to simplify workforce management and boost efficiency.

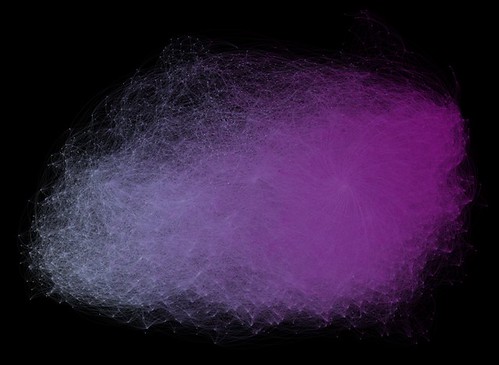

Here, in brief, is what Jockers did: He assumed that, if Author X was influenced by Author Q, then X’s texts would be very similar to Q’s. Given the work he’d already done on stylistic and thematic features, it was easy for Jockers to combine those features into a single list comprising almost 600 features. With each text scored on all of those features it was then relatively easy for Jockers to calculate the similarity between texts and represent it in a directed graph where texts are represented by nodes and similarity by the edges between nodes. The length of the edge between two texts is proportional to their similarity.

Note, however, that when Jockers created the graph, he did not include all possible edges. With 3346 nodes in the graph, the full graph where each node is connected to all of the others would have contained millions of edges and been all but impossible to deal with. Jockers reasoned that only where a pair of books was highly similar could one reasonably conjecture and influence from the older to the newer. So he culled all edges below a certain threshold, leaving the final graph with only 165,770 edges (p. 163).

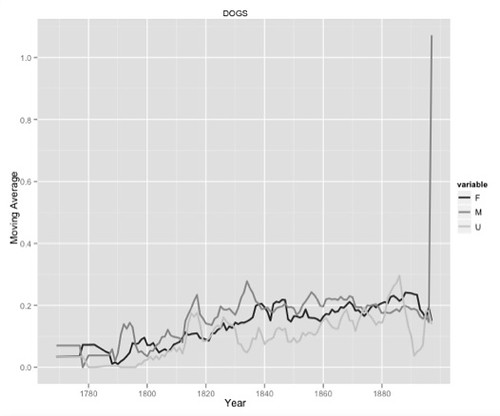

When Jockers visualized the graph (using Force Atlas 2 in the Gephi) he found, much to his delight, that the graph was laid out roughly in temporal order from left to right. And yet, as he points out, there is no date information in the data itself, only information about some 600 stylist and thematic features of the novels. What I argue in my 3QD post is that that in itself is evidence that 19th century literary culture constitutes an evolutionary system. That’s what you would expect if literary change were an evolutionary process. Continue reading “The Direction of Cultural Evolution, Macroanalysis at 3 Quarks Daily”